by Jochen Markhorst

XII The dismalest tavern of them all

I’ll see you baby on Judgement Day After midnight if you still want to meet I’ll be at the Black Horse Tavern on Armageddon Street Two doors down not that far to walk I’ll hear your footsteps - you won’t have to knock

In October 1971, journalist Pete Hamill writes a column for the New York Post entitled “Going Home”. Six young people are travelling by bus from New York to Fort Lauderdale for a beach holiday, a journey of around 24 hours. Soon, the six become intrigued by a silent, hunched man sitting a few seats in front of them. One of the girls tries to strike up a conversation. He is not unfriendly, but seems very shy and holds his tongue. It is not until the next morning, after a coffee break at a roadside restaurant, that the girl manages to get his story out of him. His name is Vingo, he has just been released after serving a three-and-a-half-year prison sentence, and is now on his way home to Brunswick, Georgia. “Wow,” says the girl. “Are you married?” ‘I’m not sure,” replies Vingo. “You’re not sure?”

In October 1971, journalist Pete Hamill writes a column for the New York Post entitled “Going Home”. Six young people are travelling by bus from New York to Fort Lauderdale for a beach holiday, a journey of around 24 hours. Soon, the six become intrigued by a silent, hunched man sitting a few seats in front of them. One of the girls tries to strike up a conversation. He is not unfriendly, but seems very shy and holds his tongue. It is not until the next morning, after a coffee break at a roadside restaurant, that the girl manages to get his story out of him. His name is Vingo, he has just been released after serving a three-and-a-half-year prison sentence, and is now on his way home to Brunswick, Georgia. “Wow,” says the girl. “Are you married?” ‘I’m not sure,” replies Vingo. “You’re not sure?”

“Yeah,” he said shyly. “Well, last week, when I was sure the parole was coming through, I wrote her again. We used to live in Brunswick, just before Jacksonville. There’s a big oak tree just as you come into town. I told her that if she’d take me back, she should put a yellow handkerchief on the tree, and I’d get off the bus and come home. But if she didn’t want me to come home, forget me—no handkerchief, and I’d keep on going.”

We all know how it ends. Twenty miles before Brunswick, a nervous, tense silence descends on the bus. The six young people crowd around the window, looking out for the old oak tree. Ten miles to go, five… When the bus pulls into Brunswick, Vingo doesn’t dare look. But then suddenly the young people start shouting, jumping, crying. Stunned, Vingo stares at the oak tree. It is covered with yellow handkerchiefs. Twenty, thirty, maybe a hundred.

The Grammy-winning liner notes Pete Hamill wrote for Dylan’s Blood On The Tracks (1975) were not Hamill’s first contribution to music history. The global hit “Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round The Ole Oak Tree” by Dawn featuring Tony Orlando, which was number one in Australia, Europe, Africa and North America two years earlier (number 2 in Argentina, so South America is only slightly less enthusiastic), and has been in Billboard’s All-Time Top Songs Top 50 for fifty years, is based on his column.

ABC television filmed the story in 1972 (with James Earl Jones as the ex-convict), and in Japan, the award-winning film The Yellow Handkerchief was based on it in 1977, but it was the million-selling hit single that really bothered Hamill. He sued songwriters Irwin Levine and L. Russell Brown, but when they proved that the story was over a hundred years old and that Hamill, too, had just heard it somewhere, he dropped the charges.

A wise decision. And Hamill has already earned his place in music history anyway. Even more honourable than with that embellished second-hand melodrama that led to a global hit: the award-winning liner notes for Blood On The Tracks definitely carry more weight than those hundred yellow handkerchiefs. Liner notes that, moreover, seem to have inspired a Dylan song years later: “The plague ran in the blood of men in sharkskin suits,” Hamill writes in the opening of his essay, and 37 years later Dylan opens his blood stained song “Early Roman Kings” with “All the early Roman Kings in their sharkskin suits” (Tempest, 2012).

Bob Dylan – Early Roman Kings (live Aug. 10, 2024):

In the meantime, Hamill continues to write and his star continues to rise. Hundreds of journalistic essays, short stories and columns, scripts and ten novels – almost all of which are set in New York, the city where he was born 1935 and where he died in 2020. Like Dylan, he is part of the fabric of the city, as Pete’s colleague with the unbeatable name Lucian K. Truscott IV puts it (Village Voice, 2 November 2016). The novels are all well-received, but perhaps the most remarkable is the widely acclaimed bestseller Forever (2003), which seems to be on Dylan’s bookshelf too.

Forever is the Homeric story of Irish Jew Cormac O’Connor, who arrives on the island of Manhattan in 1741 in search of his father’s killer. When he is mortally wounded in his attempt to free the slave Kongo, he is brought back from the dead by a grateful mystical African priestess. Brought back for good: Cormac is now immortal, as long as he does not leave the island of Manhattan. And so the immortal Cormac remains on Manhattan. He watches the settlement grow over the centuries into The Big Apple, the economic, cultural and political world power, and will continue to roam Manhattan until Judgment Day.

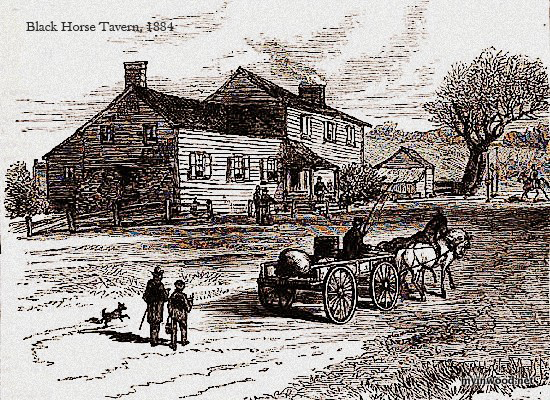

During the crossing from Ireland, Cormac has already managed to secure a job: he will be working as a printer for Mr. Partridge, who is staying at the Black Horse Tavern. And there we have Hamill’s next contribution to Dylan’s oeuvre: “I’ll be at the Black Horse Tavern on Armageddon Street,” Dylan’s narrator reveals in this fifth verse. The address is poetic licence. The historic Black Horse Tavern was in the far north of Manhattan, now Inwood, and was located at the intersection of what is now Broadway, Dyckman Street and Riverside Drive – pretty much exactly where a Starbucks is now.

Anyway, “immortality” seems to be the paddle stirring Dylan’s stream of consciousness here. We follow a Dr. Frankenstein-like narrator, the Dr. Frankenstein who became a scientist in the first place in order to play God (“the masters of science sought immortality and power; such views, although futile, were grand,” Ch. 3), and who creates a creature that will apparently outlive him: he will only see him again after midnight on Judgment Day, after the end of time. According to Revelation 16:16, this will take place immediately after the “gathering” at “the place that in Hebrew is called Armageddon” – Dylan’s associative leap from Judgment Day to Armageddon is somewhat more obvious than the immortality triple jump Frankenstein – Cormac O’Connor – Black Horse Tavern.

The gloomy street name and sombre location description suggest that the narrator does not expect to be admitted to the Kingdom of Heaven or the Garden of Eden after midnight on Judgment Day. Which is historically accurate, more or less:

“Of all bleak and dreary travesties of wayside inns, of all melancholy mockeries of old time hostelries the Black Horse Tavern is the dismalest.”

(New York Herald, July 7, 1890)

The inn could do with a makeover, as a more constructive way to express the Herald’s criticism would be. Perhaps something with a hundred yellow handkerchiefs. Surely would brighten things up.

To be continued. Next up My Own Version Of You part 13: “One of the sweetest motherfuckers you could ever meet”

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

- Time Out Of Mind: The Rising of an Old Master

- Crossing The Rubicon: Dylan’s latter-day classic

- Nashville Skyline: Bob Dylan’s other type of music

- Nick Drake’s River Man: A very British Masterpiece

- I Contain Multitudes: Bob Dylan’s Account of the Long Strange Trip

- Bob Dylan’s Rough And Rowdy Ways – Side B

- Bob Dylan’s High Water (for Charley Patton)

- Bob Dylan’s 1971

- Like A Rolling Stone b/w Gates Of Eden: Bob Dylan kicks open the door

- It Takes A Lot To Laugh, It Takes A Train To Cry b/w Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues – Bob Dylan’s melancholy blues