by Jochen Markhorst

He is quite the dreamer, our minstrel. Browsing through the collected lyrics, dreams and dream descriptions appear to be among the constants in the catalogue. After sad, cheerful and dark dreams such as in “Bob Dylan’s Dream”, “Talkin’ World War III Blues” and “To Ramona” we have already arrived at “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” on Bringing It All Back Home (1965). And it doesn’t end there. True, in the last groove, in “It’s Alright, Ma”, the poet coquettishly sighs: And if my thought dreams could be seen, they’d probably put my head in a guillotine, but that doesn’t stop him, the fifty years thereafter.

Saint Augustine appears before the nocturnal mind’s eye, in “Time Passes Slowly” (1970) the narrator experiences time delayed not only here in the mountains, but also when you’re lost in a dream, “Durango” (1975) is a bloody nightmare, “Jokerman” is a dream twister, in “Born In Time” the love couple is not made of stardust, but of dreams and so on. Up until Tempest (2012) a watchman dreams of the demise of the Titanic and in the borrowed songs of Shadows In The Night (2015) the dreaming goes on (in “Some Enchanted Evening” and “Full Moon And Empty Arms”, among others).

In short, the collected works of the master are a series of dreams.

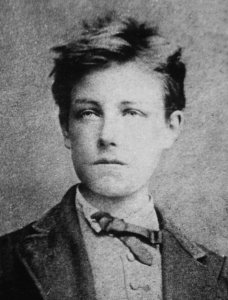

It is one of the more substantive overlappings with the work of Arthur Rimbaud (1854-1891), in whose relatively comprehensible oeuvre one reverie follows the other. Both artists even share their dreams, occasionally. Rimbaud dreams of war (in Illuminations XXXIX: Guerre – C’est aussi simple qu’une phrase musicale), as Dylan does in “Talkin’ World War III”, and the Frenchman’s Tom Thumb is a dreamer too (Petit-Poucet rêveur, j’égrenais dans ma course des rimes – Tom Thumb the dreamer, sowing the roads there with rhymes).

The director of the fascinating video clip to “Series Of Dreams” feels the connection well; in the final seconds of the clip, Meiert Avis edits the well-known youth portrait of Rimbaud in front of a musing Dylan, letters fleetingly appear and disappear: black a, white e, red i, green u and blue o – the Alchimie du verbe, the second délire from Un Saison En Enfer (1873).

The only 19-year-old genius defines poetry here as if he is talking about Dylan’s best work:

I invented the colour of vowels! A black, E white, I red, O blue, U green. – I regulated the form and motion of every consonant, and, with instinctive rhythms, I flattered myself I’d created a poetic language, accessible some day to all the senses. I reserved the translation rights.

It was academic at first. I wrote of silences, nights, I expressed the inexpressible. I defined vertigos.

‘Expressing the inexpressible’, ‘writing of silences, nights’, ‘defining vertigos’… the congeniality is also recognized in the Dylan film I’m Not There (2007). One of Dylan’s incarnations from that intriguing motion picture is a 19-year-old ‘Arthur Rimbaud’, masterfully performed by Ben Whishaw, haughty and vulnerable at the same time. He also receives the most rewarding texts, the most beautiful one-liners and aphorisms from liner notes, interviews and press conferences. Among them is the one from Shelton’s No Direction Home, which beautifully describes the Rimbaud-Dylan connection:

Yet “Series Of Dreams” is an atypical song in the series of dream songs by the bard. No extravagancies like in the 60s, nor the mystical quitened down dream references from the seventies and eighties – here the poet almost clinically administers the outlines of four dreams, some couleur is given by details such as a folded umbrella and the stage directions like the accelerated time (in a different version delayed time, by the way) and, moreover, the narrator declares: they are not too special and certainly not too scientific, none of them.

The latter remains to be seen. The founder of the scientific dream interpretation, Sigmund Freud, would know what to do with it. Any series of dreams is related anyway, as he teaches on page 171 of his Traumdeutung (1899), and despite the lack of details it is possible to predict in which direction Freud’s analysis would point.

The umbrella of course symbolizes the male genitals (“des der Erektion vergleichbaren Aufspannens wegen – because of the stretching out, comparable to the erection”), ‘climbing’ represents The Deed and ‘running’ fear – fear of dying, usually, but here Herr Doktor would probably steer towards fear of commitment. After all, the umbrella remains folded, the burning numbers symbolize the passing of the years, to witness indicates culpable passivity.

However, and on this count Dylan is right, it is not a coherent, specific interpretation, nor should it be, indeed. The poet does not describe a dream here, nor a series of dreams, but rather, after all those bizarre, melancholic, visionary and romantic dreams in his oeuvre, the act of dreaming in itself.

The fate of the song is now well known. Recorded during the Oh Mercy sessions, but to the dismay of those involved and to producer Lanois’s despair, Dylan refuses to put it on the album. His motives, as expressed in the autobiography Chronicles, are once again puzzling. After the recording, Lanois suggests something like reversing the bridge and the couplets. Dylan considers it, understands what his producer means, but then rejects the idea: “I felt like it was fine the way it was,” and then all of a sudden the song is gone. Wondrous.

His criticism of Lanois’ approach to that other rejected masterpiece, “Mississippi” from 1997, seems to point much more to his discomfort with “Series Of Dreams”:

“[Lanois] thought it was pedestrian. Took it down the Afro-polyrhythm route – multirhythm drumming, that sort of thing. (…) But he had his own way of looking at things, and in the end I had to reject this because I thought too highly of the expressive meaning behind the lyrics to bury them in some steamy cauldron of drum theory.”

A “Mississippi” recording with ‘multirhythm drumming’ is unknown, but the official releases of “Series Of Dreams” (on The Bootleg Series 1-3 and on Tell-Tale Signs) do fit that description. Still, the remarkable drumming is precisely what makes it so distinctive. The whole arrangement, but especially the percussion, provides the majestic grandeur which the sober, relativizing lyrics deny. Oh Mercy had indeed been a more beautiful album with “Series Of Dreams” on it, in this regard Lanois is unquestionably right.

It is an enchanting song. All the more remarkable is the fact that it has relatively few covers. Hard to improve or to match, that might be the reason. Most covers remain anxiously close to the source, in particular with regard to the rolling, thundering drum avalanche and the driving bass.

The single lone wolf who deviates from this, the Antwerp collective Zita Swoon for example (on Big City, 2007), is really attractive, but inevitably misses the elegant magnificence of the original.

No, the faithful copy of the Italian grandmaster Francesco De Gregori wins. Translations rarely work with Dylan songs, but ever since De Gregori’s version of “If You See Her, Say Hello” (“Non Dirle Che Non È Cosi”, on Masked And Anonymous, 2003), it is established that the Italian rendering of the Roman ‘Principe dei Cantautori‘ is the exception.

Apart from the translation, his “Una Series Di Sogni” actually adds little, but it is enough to be fascinated again. From the beautiful tribute album De Gregori Canta Bob Dylan – Amore E Furto (2015), on which also fairly loyal, but excellent cover versions such as “Dignità”, “Tweedle Dum & Tweedle Dee” and “Via Della Povertà” shine.

Pensavo a una serie di sogni

dove niente diventava realtà.

Tutto resta dov’è stato ferito,

fino al punto di non muoversi più.

Pensavo a niente di niente,

come quando ti svegli gridando

e ti chiedi perché.

Niente di troppo preciso,

solamente dei sogni così.

Italian truly is the language of dreams. Sogni che l’ombrello era chiuso.

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.