by Jochen Markhorst

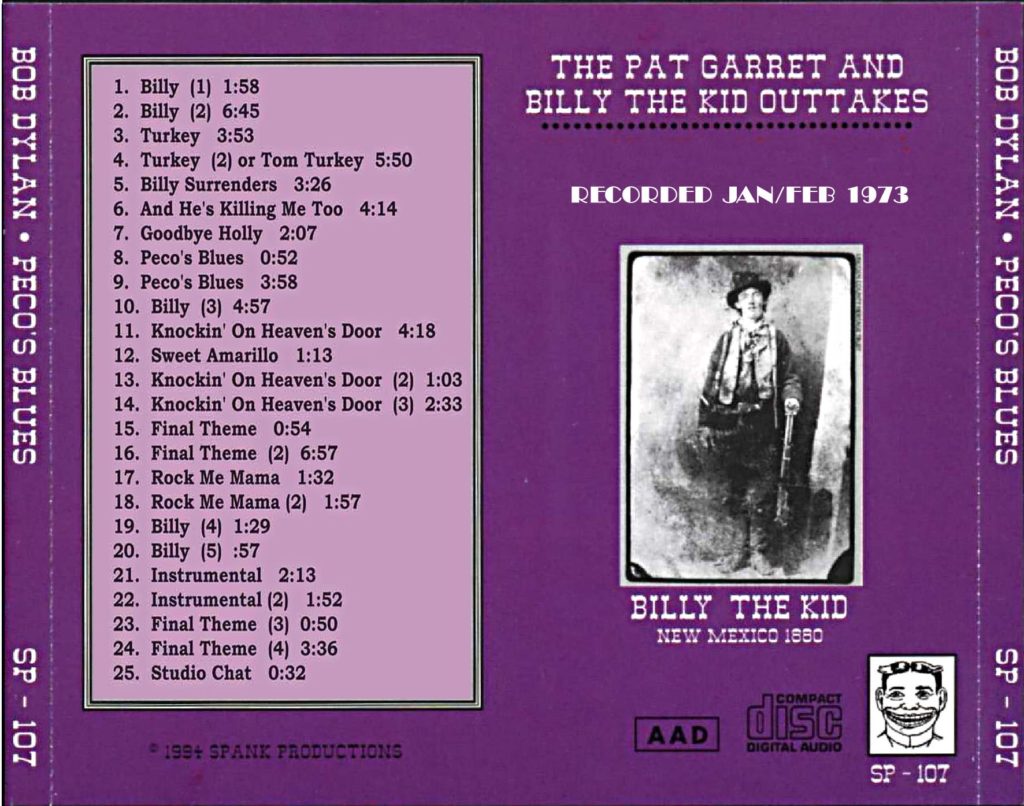

The song has since long been forgotten and covered in dust, when the teenager Ketch Secor first hears “Rock Me Mama (Like A Wagon Wheel)” in the 90s, the half-mumbled, unfinished patch of a non-existent song on Peco’s Blues (1973) , a bootleg collection of session recordings from January and February 1973 for the soundtrack of Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid.

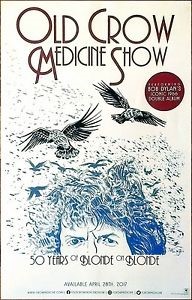

Teenagers, especially the male ones, are known to have a rather flexible prefrontal cortex, therefore they dare to ride down the hill in shopping carts, jump three floors down from the balcony into the hotel swimming pool and they do not mind messing around with a Dylan song. Ketch adds two great verses to the sketch, and merrily and often plays the song. Also he founded a band, the now world-famous Old Crow Medicine Show.

The boys record the song for a self-released EP (Troubles Up And Down The Road, 2001). In 2003 the band scores a record deal and, after copyright has been arranged with Dylan (it will be fifty-fifty), the song is recorded again, this time as the closing number for the acclaimed, untitled debut album from 2004. It is not a hit, it is not even released on single, but it is picked up. Initially by amateurs, on talent shows, by school bands, in karaoke bars and truck stops – the song is easy to play and has a high sing-along quality – but slowly and surely it seeps through to the higher echelons.

In 2013, Darius Rucker scores a number-1 hit with “Wagon Wheel” and the song finally penetrates the Great American Songbook. It yields Rucker a Grammy Award (Best Country Solo Performance, 2013) and membership of the Grand Ole Opry.

It does have a small spicy edge, Rucker’s success. Before his solo career, Darius Carlos Rucker has been the face of Hootie & The Blowfish, the band with which he records five albums and sixteen hit singles, tours around the world and sells tens of millions of records (the debut album from 1994, Cracked Rear Window, achieves sixteen times platinum and is the 14th best-selling album of all time). One of the biggest successes is the world hit “Only Wanna Be With You” (1995) and that song leads to a conflict with Dylan. Rucker has plundered Blood On The Tracks a little too enthusiastically. Starting with a chip from “You’re A Big Girl Now”:

Put on a little Dylan

Sitting on a fence

Followed by a big bite from “Idiot Wind”:

Said I shot a man named Gray

Took his wife to Italy

She inherited a million bucks

And when she died it came to me

I can’t help it if I’m lucky

And in case we still don’t get it, the last verse opens with:

Yeah I’m tangled up in blue

Dylan’s management, the thief of thoughts who has a rather double-minded attitude with regard to citing someone else’s work without acknowledging the source, mobilises lawyers, threatens with a copyright infringement indictment and eventually Hootie & The Blowfish settles the case, for an unknown, but undoubtedly substantial amount.

Nevertheless, no hard feelings with Rucker, apparently. With “Wagon Wheel” he lines Dylan’s pockets once again.

The lines quoted from the opening verse of “Idiot Wind” are the most enigmatic of one of Dylan’s undisputed monuments. The remaining 574 words can be interpreted biographically without too much reading into it; if one song justifies the disqualification Divorce Record, it is this complex put-down. And therein, in the all too easily traceable private worries of the man Dylan, the puzzle’s solution to that mysterious opening seems to lie.

In the interview with Robert Hilburn (September 2001), Dylan states:

“I overwrite. If I know I am going in to record a song, I write more than I need. In the past that’s been a problem because I failed to use discretion at times. I have to guard against that.”

That concurs with the self-criticism he voiced in 1985, in the interview with Bill Flanagan for his book Written In My Soul:

Flanagan:

Have you ever put something in a song that was too personal? Ever had it come out and then said, “Hmm, gave away too much of myself there”?

Dylan:

I came pretty close with that song “Idiot Wind.” That was a song I wanted to make as a painting. A lot of people thought that song, that album “Blood on the Tracks”, pertained to me. Because it seemed to at the time. It didn’t pertain to me. It was just a concept of putting in images that defy time – yesterday, today, and tomorrow. I wanted to make them all connect in some kind of a strange way. I’ve read that that album had to do with my divorce. Well, I didn’t get divorced till four years after that. I thought I might have gone a little bit too far with “Idiot Wind.” I might have changed some of it. I didn’t really think I was giving away too much; I thought that it seemed so personal that people would think it was about so-and-so who was close to me. It wasn’t. But you can put all these words together and that’s where it falls. You can’t help where it falls. I didn’t feel that one was too personal, but I felt it seemed too personal. Which might be the same thing, I don’t know. But it never was painful. ‘Cause usually with those kinds of things, if you think you’re too close to something, you’re giving away too much of your feelings, well, your feelings are going to change a month later and you’re going to look back and say, “What did I do that for?”

Flanagan:

But for all the power of “Idiot Wind,” there’s part of it that always cracked me up. You talk about being accused of shooting a man, running off with his wife, she inherits a million bucks, she dies, and the money goes to you. Then you say, “I can’t help it if I’m lucky.” (Laughter.)

Dylan:

Yeah, right. With that particular set-up in the front I thought I could say anything after that. If it did seem personal I probably made it overly so – because I said too much in the front and still made it come out like, “Well, so what?”

Dylan once again asserts that he didn’t think the song was too personal, didn’t think he was giving away too much anywhere. And immediately afterwards, very Dylanesque, implies the opposite: “I mean, I give it all away, but I’m not giving away any secrets.”

With that concluding remark, and with that laboriously meandering answer to Flanagan’s question about indiscretion, Dylan again confirms the often quoted words from his son Jakob, in the New York Times, 10 May 2005: “When I listen to Blood On The Tracks, that’s about my parents.”

Also noteworthy is that Dylan mentions “Idiot Wind” when Flanagan asks if he is ever indiscrete. In the same year 1985, Biograph is released, the collection box with the rich liner notes recorded by Cameron Crowe. In it Dylan states – incidentally in response to “You’re A Big Girl Now”, another one of those allegedly indiscrete songs on Blood On The Tracks – that “Ballad In Plain D” is his only confessional song. And that he still regrets that one.

Autobiographical or not, “Idiot Wind” is a masterly, heartbreaking confessional song. If not from Dylan, then from a desperate archetype Disillusioned Love Partner.

The mastery lies within the vulnerability under the rawness. The narrator is mean, unreasonable and malicious, but does not succeed in becoming unsympathetic; we all hear the pain speaking, not the man himself. A corkscrew is twisted into his heart and just like a woman who curses her husband to hell during labour, this hurt, heartbroken man damns his beloved.

So the first verse is a diversionary maneuver, as Dylan himself explains. We see a witty echo fourteen years later, when Dylan, in line with the punch line I can’t help it if I’m lucky calls himself Lucky Wilbury in The Traveling Wilburys.

A relationship with the following couplets of “Idiot Wind” there is not.

Self-pity colours the second verse, with puberal indignation: even you believe all that nonsense “they” tell me about me. Unbelievable! After all those years! The classic assertive defense, in short, of the husband who is confronted with adultery accusations. And like all adulterous spouses, this protagonist does not opt for a calm, credible denial, but for the unreasonable counterattack, trying to get into the victim role himself: how could you think that of me. My, what a bad person you are.

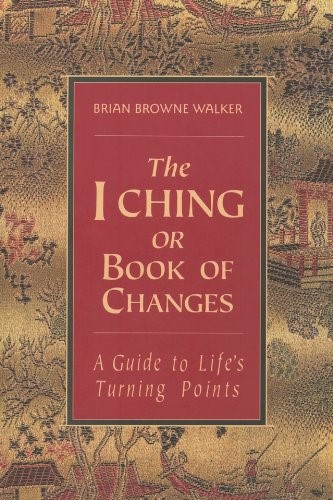

Only in the third and fourth verse does the poet of “Desolation Row”, “She’s Your Lover Now” and “Sign On The Cross” shine through again, the poet who, in the words of Joan Baez, is so good at keeping things vague. That third verse opens with other words than the original version from New York. Initially Dylan sings I threw the I-Ching yesterday, it said there might be some thunder at the well, a line the bard probably rewrites because it might seem too personal – in ’65 he publicly, in an interview with the Chicago Daily News, stated:

“There is a book called the “I-Ching”, I’m not trying to push it, I don’t want to talk about it, but it’s the only thing that is amazingly true, period, not just for me. Anybody would know it. Anybody that ever walks would know it, it’s a whole system of finding out things, based on all sorts of things. You don’t have to believe in anything to read it, because besides being a great book to believe in, it’s also very fantastic poetry.”

The man Dylan apparently really has something with this Book Of Changes, so on closer inspection the poet prefers to omit a reference to it. Instead, he opts for the equally mystical, but somehow more run-of-the-mill I ran into the fortune teller, who said beware of lightning that might strike. In terms of content, no major difference, of course: both variants describe a supernatural entity warning of a fatal, major event. Also not too far from the person behind the poet, by the way; from his autobiography Chronicles we can conclude that Dylan is not completely insensitive to the transcendent. Concepts such as fate, destiny and spiritual come along dozens of times, even when he documents something as everyday as a break-up (in this case with Suze Rotolo): “Eventually fate flagged it down and it came to a full stop.”

Evoked images and chosen language in the continuation of this occult opening line seem familiar. A lonely soldier on the cross, a chestnut mare, the accumulation of antitheses (peace / war, truth / lies, he won after losin’, woke up / daydreamin) … familiar Dylan territory. The image of the smoke-emitting freight car (smoke pourin’ out of a boxcar door) is such an image that could have surfaced in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” or “Farewell, Angelina”. Impenetrable, but a strong stage piece, a piece scenery for a painting by Dalí or a twentieth-century Hieronymous Bosch – Dylan now and then succeeds in his intention to make the songs on Blood On The Tracks “like a painting”. That probably also explains the textual intervention with this excerpt. Originally watchin’ falling raindrops pour; from a radically different perspective, and visually much less strong than that smoldering wagon.

Bitter revenge, however, colours the last, lurid lines, in which the narrator accuses his beloved of hurtful lies and daydreams about her fate: her corpse in a ditch, flies buzzing around her dead eyes and her blood dripping along the saddle of that chestnut mare. A macabre, cinematic image that the thief of thoughts with a sense of tradition borrows from a nineteenth-century cowboy ballad, from “There’s Blood On The Saddle,” recorded in 1937 by the renowned Alan Lomax for the Library Of Congress.

This structure the poet extends in the fifth and sixth verse. Again a mystical opening (“destiny broke us apart”), a series of contradictions (good / bad, upside down, top / bottom, spring / autumn, I waited on the running boards), another hint to the yin yang of the I-Ching (the good is bad and the bad is good) and highly visual, wild metaphors. “You tamed the lion in my cage” can be placed, but what about “The priest wore black on the seventh day”? One might hear an echo of “Highway 61 Revisited” and as a character he fits effortlessly on Blonde On Blonde, but what bussiness does that priest have here? And why is the storyteller waiting on the running boards, at the cypresses?

The poet achieves at least the same as in the third verse: the setting in which his lying, blinded and shameful beloved is residing, is a filled tableau, perhaps in California, the land without seasons, and otherwise in an expressionistic representation of a Promised Land – it is, after all, both spring and fall in these parts, time is defied.

The real pain, bitterness and despair the poet saves for the last verses. The opening lines of the seventh verse are the most abrasive of the entire song. The narrator here exposes himself to such an extent that the listener gets the uncomfortable feeling of unwittingly reading someone else’s diary: he no longer tolerates her touch, not even indirectly, sneaks past her closed door … this is getting too painful. In that furious live version from ’76 (on Hard Rain), Dylan puts it even more lachrymosely: “I can’t even touch the clothes you wear, very time I come into your door, you leave me standing in the middle of the air.”

In the earlier version, from September, the poet opens this seventh verse less whiny. There he even expresses a shared guilt: We pushed each other a little too far, and he describes the inconvenience of the silent treatment (“In order to get in a word with you, I’d have had to come up with some excuse”).

Three months later, in Minnesota, the poet deletes those resignated lines and reignites the vindictive slander again. Awkward is the hurtful, childish self-pity with which the narrator tries to throw the final jabs, hooks and punches (“You’ll never know the hurt I suffered”) and the ridiculous, misplaced, acted superiority of the punchline it makes me feel so sorry.

Multicoloured and complex enough, those eight verses, but the status and reputation of the song are coined by the false, cutting chorus, in which the disillusioned narrator ad nauseam argues what an imbecile his ex-lover is. Of mythical proportions, is her silliness. When she starts speaking, the IQ drops from the Grand Coulee Dam (in the state of Washington, in the far west) to the Capitol (in Washington, D.C., in the far east), so throughout the country. The backwardness of her words stirs up dust, fluttering curtains, blows through our coats and desecrates the letters we wrote. The chorus is, in short, a put-down that even surpasses “Like A Rolling Stone”, “Positively 4th Street” and “She’s Your Lover Now” in malice. That false personality shift from the last chorus (“We’re idiots, babe”) does not alleviate it.

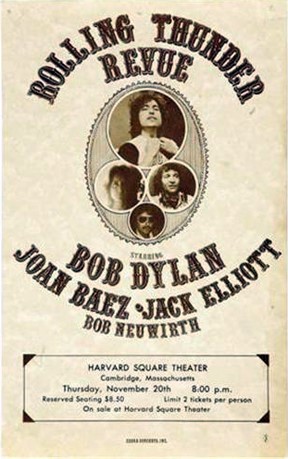

The intensity of Dylan’s rendering (“black energy and poison,” as band member David Mansfield calls it) during the Rolling Thunder Revue, the 1976 concert tour, makes it difficult to ignore personal, intimate involvement with the words sung. Here is really an artist who exposes the person behind the artist. Tension releasing, presumably, and after 1976 the bard seems to be relieved; “Idiot Wind” disappears from the set list. In the following years, however, the song remains a topic of discussion in interviews, sometimes at the initiative of Dylan himself, as in the above conversation with Flanagan in 1985. Or in 1987, when the director of the “multi-media musical” Dylan: Words & Music, Peter Landecker, says that he has spoken with Dylan:

The intensity of Dylan’s rendering (“black energy and poison,” as band member David Mansfield calls it) during the Rolling Thunder Revue, the 1976 concert tour, makes it difficult to ignore personal, intimate involvement with the words sung. Here is really an artist who exposes the person behind the artist. Tension releasing, presumably, and after 1976 the bard seems to be relieved; “Idiot Wind” disappears from the set list. In the following years, however, the song remains a topic of discussion in interviews, sometimes at the initiative of Dylan himself, as in the above conversation with Flanagan in 1985. Or in 1987, when the director of the “multi-media musical” Dylan: Words & Music, Peter Landecker, says that he has spoken with Dylan:

“We talked about the show, which songs are included and why. Dylan asked if Idiot Wind was in. I said no and asked why he singled out that one. “It’s one of the most theatrical, dramatic ones”, he said.”

And in ’91, in the interview with Paul Zollo for SongTalk, Dylan goes into the work in more detail. It even seduces him into an atypical expression of pride. Regarding the different text versions of “Idiot Wind”, the poet states: “There could be a myriad of versions for the thing. It doesn’t stop. It wouldn’t stop. Where do you end?”

Dylan then pays some attention to people’s reactions to his songs and concludes his answer to Zollo’s question about “Idiot Wind” with a modest, yet satisfied, qualification:

“There’s just something about my lyrics that just have a gallantry to them. And that might be all they have going for them. [Laughs]. However, it’s no small thing.”

That is intriguing. Of all songs, Dylan chooses “Idiot Wind”, one of the most nasty and indiscrete songs in his oeuvre, to articulate a comprehensive qualification of his lyrics: they have a gallantry. That, as we can expect from Dylan, is by no means a unambiguous valuation. “Gallantry” can mean courage, fearlessness, as well as elegance, nobility, courtesy. The rest of the interview, Dylan is pretty clear, informative and serious, so we can assume that he is not throwing one of his good old smokescreens here, but that he means what he says.

In that case we can delete the meaning courtesy; Dylan himself also acknowledges that battery acid is the fuel of this song and would agree it is not really courteous, well-mannered to sing someone’s poor mental capacities for almost eight minutes.

Then remains: courageous, brave, fearless, “gallantry” as the opposite of cowardice. There is something to be said for that. At least: with this specific song. The narrator is not afraid to expose himself, that much is true. Whether, and to what extent, the qualification also applies to Dylan’s catalogue at all is another question. Among the majority of the Dylan followers, the word courageous will not come up to characterize the man’s work. At public praises such as the Oscar ceremony or the Nobel Prize enough adjectives are listed to praise Dylan’s work, but practically nothing that comes close to bravery. In fact, Dylan is pretty much the only one who repeatedly points out the gallantry of his work. Here, in this conversation with Zollo, as he also does in the (not too serious) interview with Jonathan Cott for Rolling Stone in 1977, alleging that the driving force behind Blood On The Tracks in general and “Idiot Wind” in particular is willpower. And again, for example, in his reaction to winning an Oscar for “Things Have Changed”:

“I want to thank the members of the Academy who were bold enough to give me this award for this song, which obviously… a song that doesn’t pussyfoot around nor turn a blind eye to human nature.”

Lofty words, but it is highly questionable whether the jury members recognize their choice in Dylan’s words. “Things Have Changed” is a beautiful, Oscar-worthy song, but a song which doesn’t pussyfoot around? The lyrics are full of disguising language (“some things”, “so much”, “things have changed”, “lot of other stuff” and so on) and dark imagery. “I’ve been walking forty miles of bad road” (Dylan writes in the fortieth year after his first record). A feeling comes over him as if he wants to put a worshiped lady in a wheelbarrow (?). The “next sixty seconds could be like an eternity” (the singer sings exactly sixty seconds before the end of the song). And the ultimate enigmatic verse of the last middle-eight, about one Mr. Jinx and Miss Lucy who jumped into a lake.

All in all, Dylan clearly has a different definition of gallantry, of boldness or courage, than the average jury member or the average Dylan follower.

All that talk about “Idiot Wind” leads to an unexpected, short revival: 1992, we are in Australia and suddenly “Idiot Wind” is on the setlist again. In Melbourne, April 5, he announces the song with the surprising words “Thank you, that was a recent song,” but presumably Dylan means the song he played before (1990’s “Cat’s In The Well”). In California, a few weeks later, he calls it an old song. He does not comment further on the unexpected choice, or on the song at all.

They are beautiful performances. The singer mainly follows the Blood On The Tracks version, the lyrics are not completely accurate and two couplets are dropped in favour of a harmonica solo. Nothing is left of the fury of sixteen years earlier (obviously), but more love has been given to the musical accompaniment – an ebb and flow arrangement with a spotlight on the steel guitar, giving the song an attractive country atmosphere.

Dylan plays it forty times, that spring and summer of ’92, and then brings the song ‘home’; the performance in Minneapolis, 30 August, is the very last one.

The colleagues stay far away from “Idiot Wind”, although the song is usually somewhere in the top 20 in the various lists of Best Dylan Songs. It is understandable, this restraint; too personal, despite everything the master undertook to make it only seem personal.

Mary Lee’s Corvette of course cannot avoid the song, when (magnificently) performing an integral Blood On The Tracks: Recorded Live At Arlene’s Grocery (2001), but with “Idiot Wind” singer Mary Lee Kortes loses track sometimes. The band makes up for a lot.

Safer, because instrumental, is jazz guitarist Jef Lee Johnson, who passed away too early, on his beautiful tribute album The Zimmerman Shadow (2009), a record with bold, mostly successful interpretations of sometimes exotic, exurbantly fanning out Dylan songs (“As I Went Out One Morning” develops into an exciting , fierce Jimi Hendrix-like 11-minute jazz exercise, for example). Johnson’s “Idiot Wind” remains serene and is supported by a tasteful, funky bass part, over which Johnson plays a partly pointy, partly dreamy guitar part – very attractive.

The only other notable professional cover is from The Coal Porters, the British-American bluegrass band of the respectable Dylanologist Sid Griffin, author of two excellent Dylan books. The first album, How Dark This Earth Will Shine (2004) is very nice, the bluegrass version of the old punk hit “Teenage Kicks” (The Undertones, 1978) is great, but “Idiot Wind” is a less fortunate choice; the veranda atmosphere does not really fit the song.

The amateurs are as enthusiastic as the pros are reluctant. YouTube is teeming with, mostly pathetic, living room recordings, though the diversity is striking. Lots of spectacled, white males in their fifties, of course, but also surprisingly many younger hipsters, blushing, shy teenagers and even some local heroes with homemade translations (Swedish and Hebrew, for example). Artistically not too uplifting, but it does reflect the indestructible appeal of the song over the decades.

The Old Crow Medicine Show has not risked it either. The band received a lot of applause in 2016 with the tribute 50 Years Of Blonde On Blonde, the live registration of a complete rework of that legendary album. The accompanying tour, which leads the men to Europe as well, is just as successful, their “Wagon Wheel” was awarded an official Seal Of Approval from the master himself, as well as the successor “Sweet Amarillo” (at Dylan’s request completed by Ketch Secor and his men), so in 2025, at the fiftieth anniversary of Blood On The Tracks, we can expect the next recommendable cover of “Idiot Wind”.

See: Bob Dylan and Baudelaire (Part III) and Isaiah 44:14 –

“He heweth him down cedars, and takes the cypress and the oak….”

The cypress tree is a symbol, for Dylan and Baudelaire, an emotional search by mankind for something that’s strong and endures in a world where nothing lasts, where spring turns into autumn, and churches made of wood burn and of stone fall ….

Notre Dame is burning…

The cedar tree is featured on he flag of Lebanon.

Steadfast is Puritan poet and minister Edward Taylor in his religious faith that his soul will endure forever beyond the body’s limited existence in a corrupt physical world that he finds figuratively, if not literally, burning:

Such fireballs dropping in the temple flame

Burns up the building: Lord, forbid the same

(An Address To The Soul Occasioned By A Rain)

Bob Dylan juxtaposes the image of the priest which indicates his emotional faith in the endurance of a secular love relationship is tempered somewhat when faced with the reality of the situation – granted, he reluctantly admits, that maybe he’s partially to blame:

The priest wore black on the seventh day

And sat stoned-faced as the building burned.

* the flag/ stone-faced

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/286/Idiot-Wind

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.

Robert Zimmerman will hopefully be forgotten very soon. What a mess… Can’t write – Can’t sing, – Can’t play. No next paragraph.

It is comments such as this from SK Yeatts that add to the view that there is indeed something worth considering in Dylan. To imagine that one can dismiss the entire body of work of the second most productive popular songwriter in the English language of all time, in 18 words takes a level of arrogance that is hard to imagine. But what a world you must live in SK Yeatts – to believe that something out there that attracts millions upon millions of people can be dismissed by you in around 20 words reveals a level of arrogance that is quite extraordinary.