by Jochen Markhorst

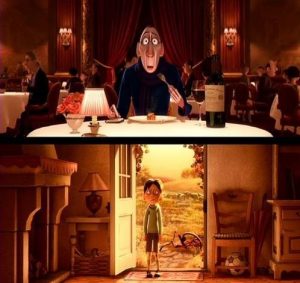

Nothing triggers the mémoire involontaire, the spontaneous memory, so strongly as scent does. Marcel Proust, who has coined the term, blames the breakthrough of childhood memories in À la recherche du temps perdue (1913) on the taste of the madeleine cake that is dipped in lime blossom tea, but our taste sense is actually too crude for that. It must have been the scent that triggered the narrator’s olfactory memory. Like how with Anton Ego, the feared restaurant critic in Pixars Ratatouille (2007), the explosive flashback to his deeply cherished childhood memory is not due to the food, but to the smelling of Remy’s masterpiece, as the smell of frying chicken carries Kris Kristofferson back to a long-lost dearness (“Sunday Morning Coming Down”, 1969), and as only the memory of The Scent Of A Woman (1992) can still enthrall the bitter, blind Colonel Frank Slade (Al Pacino).

Our olfactory nerves are plugged directly into the cerebral cortex. All other sensory perceptions first make the detour via the thalamus and are filtered there, and are briefly weighed up and weighed in on the importance of passing on to our consciousness or not, but smells are allowed to pass unhindered.

In Dylan’s mini-novella “Floater (Too Much To Ask For)” it is also a scent that triggers a Proust-like stream of memories with the narrator, the scent of burning softwood in this case. The narrator, presumably a floater, an odd-jobber perhaps, is on his way to an unpleasant task; he is going to kick someone out. His reluctance makes him susceptible to distraction; on the way, light, smells, sounds and images seduce him to flee into reminiscing.

Rural idyll, that might be the easiest way to summarize those memories. A slow, lazy summer day, in love with a second cousin, bobbing in a boat as he catches one catfish after the other. A setting like in The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (Mark Twain, 1876), presumably somewhere in Mississippi, Tennessee, or, given the tobacco reference, perhaps Virginia. Floating Along on the man’s dream sites, fractions of his life story do loom up. Raised in a harmonious family, in a family that apparently has been at home here for generations. And presumably that is one of the reasons he never got out of here, unlike most of his classmates.

The floater did stay, has given up its dreams and is now rummaging around without much ambition. Choice of words and the reference to the boss suggest that his livelihood is not very honourable; he has become one of those hangers-on, of the followers who do dirty jobs for the boss – like kicking someone out.

Perhaps. Or he will show his life partner, that second cousin, the door. She wants him to give something up, and she may shed tears all she wants – it’s too much too ask.

The ambiguous title points at a more criminal interpretation, though (a floater being a floating, unidentified corpse) and, more importantly, the most important source of the text: the Japanese gangster epos Confessions Of A Yakuza by Dr. Junichi Saga.

Dylan copies and paraphrases no fewer than eight text fragments – 144 of the 475 words, approximately one third, come almost directly from Saga’s novel. Among them memorable lines, like the punch line. At Saga it says: Tears or not, though, that was too much to ask. And the other 331 words are also hardly Dylanesque. A word like “dazzling”, for example, is nowhere to be found in Dylan’s abundant, word-rich catalog. Yes, one time in his autobiography Chronicles, but there he quotes from an age-old folk song (“Roger Esquire,” another song learned from Webber, was about money and beauty tickling the fancy and dazzling the eyes).

The word is somewhat archaic. In the work of Herman Melville, so admired by Dylan, it is used dozens of times (’tis good as gazing down into the great South Sea, and seeing the dazzling rays of the dolphins there, Redburn, 1849) and the English translators of Proust sometimes choose it too (for example On this day of dazzling sunshine, to remain until nightfall with my eyes shut was a thing permitted, from the fifth part of the Temps Perdue, ‘The Captive’, 1923).

The same applies to the unusual squall (blast, gust of wind, but Dylan also plays with the figurative meaning trouble, arguments) in the fourth verse; it is the first and only time that Dylan uses it. Melville uses it twenty-six times alone in Moby Dick, a multiple thereof in his collected works.

Now, since the Nobel Prize acceptance speech, we know that Moby Dick is in Dylan’s personal top three, so it’s not too surprising if idioms and twists and turns from that monument descend into his lyrics.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oyTKhgzNTiA

The music of “Floater” also does justice to the album title “Love And Theft”. Lovingly stolen, almost note by note, from “Snuggled On Your Shoulder (Cuddled In Your Arms)”, a 1932 song by Carmen Lombardo and Joe Young. The first version is recorded by Bing Crosby, who, still in 1932, manages to score a nice hit. It is likely that the original version is Dylan’s template. The best-selling record artist of the twentieth century (it is estimated that Bing Crosby has sold more than a billion records, “White Christmas” has been sold some hundred million times, according to Guinness World Records) is also idolized by Dylan. In his radio show Theme Time Radio Hour, Crosby comes along three times and twice Dylan takes a closer look at him, both times implicitly honouring the crooner as the founder of vocal jazz:

“One of the most influential singers in the 20th century. He changed the way we listen to singers. Before him, singers had to belt it out. …. to sing over a loud band in a concert hall. Emerging microphone technology allowed Bing, to add a level of subtlety, nuance and insinuation.”

(Theme Time Radio Hour, episode 13)

And with an admiring quite a man, quite a singer, the radio host closes his tribute.

For “Floater”, Dylan increases the pace of Crosby’s “Snuggled On Your Shoulder” a bit, but he tries to stay close to the sound. The stomp is absent in the more sentimental original, which was recorded without percussion, but the prominent role for the lonely violin in both songs is decisive in terms of atmosphere and sound. Dylan’s production is clear, clean, and yet the band achieves the grit of a 1930s recording – mainly thanks to the drummer, as he lets his cymbals rustle under the violin and steel guitar in the intermezzi. And thanks to the voice of the master, of course.

The singer Dylan delivers a first-rate performance again in this song. When cutting and pasting the text fragments gathered from here and there, the lyricist has only limited concern for the number of syllables, for the exact fit of the words. He apparently trusts his extremely flexible phrasing. Which does not, indeed, abandon him; the shortest couplet, the summer breeze couplet, has 29 syllables, the longest is the Romeo and Juliet couplet and is almost double of that (52). Dylan lays out that word procession in as many bars, in as many seconds, without cramming, without being forced or rushed – as he manages throughout the song to nail the vibe that he admires in Bing Crosby: Bing was able to sing more conversationally (Theme Time Radio Hour, episode 99).

Dylan himself is content with the song. He plays it some ninety times between 2001 and 2007. The colleagues are less enthusiastic, and that is understandable. The antique atmosphere of the song, the required vocal acrobatics … and anyway: it is not really a Dylan song. Covers can therefore only be found in the tribute circuit, but none of them is worth looking up. Except for one: the praised jazz trio Jewels & Binoculars, the trio around saxophonist Michael Moore that specializes in melancholic, compelling, instrumental performances of Dylan songs. As breathtaking as “Visions Of Johanna” and (especially) “I Pity The Poor Immigrant” it is not every time, but their “Floater (Too Much To Ask)” on the album Floater (2004), for which Moore chooses the more the appropriate clarinet, is wonderful. Of course, he doesn’t have to sing it, the lucky wilbury.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/192/Floater-Too-Much-to-Ask

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.