by Jochen Markhorst

Lodi is a small town in San Joaquin County, located somewhere in the middle of California. On the official website, Lodi likes to present herself as a sunny, prosperous town that owes her fame to being a succesful producer of wine grapes, even as Zinfandel Capital of the World, and it proudly points to the 2015 Wine Region Of The Year award.

All very enviable and impressive, but of course Lodi does not owe her fame to that. For that the town would have to thank Creedence Clearwater Revival, for writing the B-side of the world hit “Bad Moon Rising” from 1969: “Lodi”.

But alas, in that catchy song, which soon becomes just as popular as the A-side, John Fogerty certainly doesn’t put the town in a sunny spotlight. With the refrain line Oh Lord, I’m stuck in Lodi again the local tourist office won’t be too gilded. Fogerty doesn’t mean it personally, as he later explains. Though he comes from Berkeley, a hundred kilometers away, he has never actually been to Lodi when he writes the song. However, it has the coolest sounding name, hence Fogerty’s location choice. It is pronounced as lo-dai, and indeed, with the foregoing Lord I’m, the refrain runs like a charm.

Nevertheless, the official authorities prefer to ignore the song. On the clumsy but very extensive site www.lodi.gov more than a hundred historical dates of interest since 1869 are remembered, including immortal highlights such as the production of 3000 wagon loads of watermelon in 1886 (“grown without irrigation!”), the first Lodi Grape Festival in 1934 and the dedication of a new police facility in 2003. But becoming world famous in 1969 through Creedence’s song is not mentioned anywhere. Incidentally, it is a less sensitive matter to the residents and the middle class; at local festivals, fairs and other events there is always a banner somewhere with Fogerty’s famous one-liner and sometimes Oh Lord I’m stuck in Lodi again is even the motto on such an occasion.

After the painful break with his bandmates in 1972 and especially due to the shameful stranglehold contract with manager Saul Zaentz, Fogerty refuses to play his old Creedence hits for a decade and a half. In the end it is Bob Dylan who pushes him back in the right direction, he tells in the interview with Uncut, March 2018. He describes the run-up in more detail in his autobiography Fortunate Son (2015). In February 1987 he talks to Dylan after a spontaneous performance with George Harrison at a Taj Mahal concert in Los Angeles. At the request of the audience, Dylan plays one of his own songs, then it is George Harrison’s turn with “Honey Don’t” and “Twist And Shout”.

“For three minutes I sang “Ooooh” directly across a mic from George Harrison, like the Beatles on Ed Sullivan. That was an amazing feeling. Bob said, “All right, John, we’ve all done a song. Do Proud Mary.”

“Sorry, Bob,” I told him. “I’m not doing my old songs. I don’t do them anymore.” I was being kind of difficult, and I knew it. And instead of arguing about it, Bob Dylan, in his genius and ever so influential way, said, “If you don’t do Proud Mary, everybody’s gonna think it’s a Tina Turner song.”

There was no way out now. I thought, Bob Dylan just told me I’d better play my song or it’s gonna turn into a Tina Turner song. It was something only a musician could do—get out from under all the crap and find a way. So I played “Proud Mary.” And enjoyed it. Immensely.”

“Dylan’s words were very provocative and he certainly put the bee in my bonnet, you could say,” Fogerty admits in that same Uncut interview. A few months later, he plays at a benefit concert for Vietnam veterans and, for the first time in all those years, he plays “Fortunate Son”, “Who’ll Stop The Rain” and all those other CCR classics.

It is not the first or only time that Fogerty recognizes Dylan’s influence. In that autobiography he admires the songwriter Dylan in no uncertain terms and when a sweet-talking radio maker calls him the voice of a generation (SiriusXM, October 16), he shrinks back: no, no, that’s Dylan. In an interview with American Songwriter, May 2013, he can’t even come up with the right superlatives to do justice to the bard’s influence:

“Bob Dylan, you will never be able to overstate his importance, his cultural impact at that time. No matter how much exaggeration and hyperbole you use about Bob Dylan, you still haven’t said it enough: If any one guy was responsible for ending the war in Vietnam, then it’s Bob Dylan. Because millions upon millions of young people hearing his music, dissecting his words, becoming children of his poetry and having a cultural point of view, it’s all kind of in Bob’s image, in his shadow.”

And the most tangible that influence is of course in his songs, like in “Lodi”, in which Fogerty varies on Dylan’s “Stuck Inside Of Mobile”.

In 1978, Dylan returns the compliment by reusing another line from “Lodi” for the obscure “Legionnaire’s Disease”. With a somewhat macabre twist, though. Where Fogerty sings If I only had a dollar for ev’ry song I’ve sung, Dylan sings I wish I had a dollar for everyone that died.

That is not the only strange thing about the song. The place in the man’s catalog alone is quite unique; Dylan never recorded the song or performed it on stage, but in 1981 the copyrights are protected, the lyrics are incorporated in The Lyrics and on the site. Comparable at most to the fate of “Love Is Just A Four Letter Word”.

In addition, the subject is alien. Legionnaires’ disease (Dylan misspells it Legionnaire’s), or legionellosis, a severe form of pneumonia, is detected in 1976 after an outbreak of the disease when 221 veterans, who are staying in the same hotel in Philadelphia for a reunion of the American Legion, get infected with the bacterium that we have named since the legionella pneumophila bacterium.

It is actually quite unusual, such an acute and above all fleeting approach by a Dylan song. Other topical songs, such as “George Jackson” or “Who Killed Davey Moore” have a historical incident as a source of inspiration too, but on top of that have a timeless, the anecdote transcending value. Here at “Legionnaire’s Disease” we see an attempt to do so, in that strange last verse, but it doesn’t really get off the ground. The concept of the veterans’ disease is simply too specific to disconnect from the content, too explicit to gain a metaphorical quality.

There is some Dylanesque word play and art. Not much, but at least more than in most Slow Train Coming songs, which he will write after this song. Got ’em hot by the collar is a catachesis, a non-existent expression, and seems to be composed of hot under the collar and to get by the collar. Plenty of old maid shed a tear has an archaic, nineteenth-century colour, just as put on a squeeze is rather a gangster idiom from 1930s films, and semantically does not fit here anyway.

The bard himself is not too proud of it, apparently. He uses the song only for the sound check, just as he seems to dash off more songs that remain unpublished in those days, and then soon rejects the song.

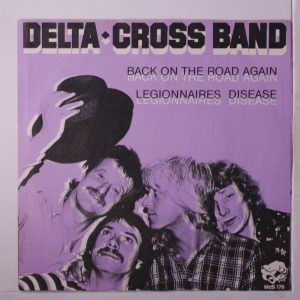

But guitarist Billy Cross, from the backing band, is fond of “Legionnaire’s Disease”. Two years later, when Billy’s Dylan experience is already a thing from the past, he strikes a record deal with his Danish friends from the Delta Cross Band. Cross still has an old tape from a Detroit sound check, and that is enough to convince his band members: for the album Up Front (1981) they produce the first official recording of this Dylan song.

The recording also makes it more clear why the master left the song behind – that bit between the verses is very much like “Like A Rolling Stone”. Reparable – Dylan would undoubtedly have rewritten it or thrown it out for a possible recording – but hey, he has plenty of new songs this month in 1978. And Dylan really, really hates to repeat himself, studio engineer Chris Shaw explains in 2008:

“He just hates it. A lot of times on “Love & Theft”, he’d do a version of a song and he’d say, “Aww, I’ve done that already. We gotta figure out some other way of doing it.” That’s really what it’s all about with him.”

With or without that Rolling Stone snippet it is a great song, but it does not survive. That admirable resuscitation by Billy Cross is also the song’s only notable version. There are still some poor versions by tribute bands, but colleagues from the higher echelons ignore “Legionnaire’s Disease”, just like Dylan himself does.

John Fogerty would be the ideal candidate, obviously. During his concerts in 2018, he always plays four or five covers between solo work and CCR classics. “Jambalaya” of Hank Williams, The Who’s “My Generation”, “My Toot Toot” of Rockin ‘Sidney, “When The Saints Go Marching In”, The Beatles, Gary U.S. Bonds, Sly & The Family Stone… an obscure gem from Dylan’s Secret Catalog certainly would fit in harmoniously.

Delta Cross Band:

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/350/Legionnaires-Disease

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.