by Jochen Markhorstf

In Chronicles, the autobiographer recalls that producer Bob Johnston is trying to tempt him to come and record in Nashville. The first impressions and associations are not too positive:

“The town was like being in a soap bubble. They nearly ran Al Kooper, Robbie Robertson and me out of town for having long hair. All the songs coming out of the studios then were about slut wives cheating on their husbands or vice versa.”

But in the end they do go into that Nashville studio to record the monument Blonde on Blonde … the album with all those songs in which the protagonist tries to seduce one rainy day woman after the other, is scratching the door of someone else’s wife or himself is assaulted by some slut wife cheating on her husband. The studio air there is infectious, apparently. Not until side 4, until “Sad-Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands”, the protagonist will ultimately find erotic peace and finally face the One.

However, we are not there yet. We are on side 3 of the double album, at the elegant blues “Temporary Like Achilles”, and are witnessing yet another amorous disaster. The ninth, to be precise.

In “Pledging My Time” the pleading narrator stays in the cold, and the following Johanna remains a vision. The pushy girl from “Sooner Or Later” is being rejected with some difficulties, the desire for the adored from “I Want You” is still unfulfilled, so the Queen of Spades needs to offer some comfort. There are, of course, enough friendly ladies further down South, in Mobile. Mona, and a French girl, and Ruth, and a debutatnte who knows what he needs, but none of them really interests him, at least not so much as the fatal woman with her “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat”. But alas, she is another slut wife cheating on him with the doctor.

Some love happiness promises the relationship from “Just Like A Woman”, but unfortunately, she turns out to be a pathetic poseuse – she is rather cooly discarded. One song later it’s the beloved from “Most Likely You Go Your Way” who is viciously boned out and ruthlessly dumped.

But: we are approaching the end of Lover’s Lane. After Achilles, the loser will still have to be humiliated by Sweet Marie, who once again is painting the town red, he has to make one more big mistake in “Fourth Time Around” and in conclusion falls into despair in “Obviously Five Believers” … and then he may finally, at last kneel down before the One, the Nonpareil with the smoky eyes and a voice like a chime, with her silky body and her glass face; his Sorrowful Dame from the Nether Countries.

The honey from “Temporary Like Achilles” is just as unapproachable as Sweet Marie and Johanna, forces the desperate lover on his knees and thus exhibits a side of the narrator we don’t see often: helpless, upset, no trace of the usual bravado or superiority, let alone of his vicious, sharp tongue. No, this suffering even lowers him to stalking, he is scratching at her door and is being treated like a nasty bug; honey sends her current boyfriend, her “guard” Achilles, out, who denies him entry and drives him out of the alley.

In earlier versions of the text, the rejected lover is submitted to a treatment even harsher: “I get beat up and sent back by the guard”.

Humiliating. But a bit more in line with the associations that are evoked by the choice of that loaded name Achilles, who was, after all, a first-rate jaw crushing ferocious fighter.

This choice of name is, obviously, the most striking thing about this song, but it doesn’t seem to be much more than name-dropping. Dylan does have some knowledge of ancient myths and classical Greek and Roman literature; in high school he attended the Hibbing High Latin Club for two years, and in Chronicles he tells he thanks a large part of his knowledge to the bookcase in one of his places to stay, in his first year in New York.

For the time being, that knowledge only indirectly trickles into his work. Later, in the twenty-first century, he loots exuberantly from the work of, for example, Ovid (in “Ain’t Talkin’”, 2006) and Vergilius (“Lonesome Day Blues”, 2001), but in the decades before it is limited to a single name or a single image.

In doing so, the poet is aiming more at the comic effect of alienation in the 1960s; the closing, nonsensical bottom note in his experimental prose-poem Tarantula (written ’65 / ’66, published in 1971) is signed by “Homer the slut”, the same Homer receives a meaningless name check in the cheerful homage “Open The Door, Richard” (“Open The Door, Homer”, Basement Tapes) and Phaedra pops up, too (“I Wanna Be Your Lover”). In the 70s and 80s, names such as Jupiter and Apollo and references to, for example, Hercules (“Jokerman”) and Odysseus (“Seeing The Real You At Last”) sometimes drop by, but they are no more than superficial references.

In the run-up to that symbolic name, we see the usual uncommon foggy poetry of Dylan’s lyricism in these years. The opening line is already disruptive: “Standing on your window”? A thoughtful mistake, we learn from the unsurpassed Cutting Edge. In the first take Dylan sings “Standing ’neath your window”, (semantically correct) in the aborted second take “Standing at your window” (nothing wrong with that) and in the third take the poet decides for the confusing on.

This play with words is not limited to the innocent prepositions. The I-person feels “harmless” and is languishing at her “second door”, the first couplet also reveals. Harmless, the listener only thinks in the second instance, is quite weird. Desperate, unhappy, lonely, that all fits. But “harmless”? Can a person feel “harmless“? Second door is equally strange. The expression has no figurative meaning, does not exist as a metaphor.

And yet, despite the linguistic inaccuracies, the image that Dylan conjures up is crystal clear: a pathetic, worn-out and excluded loser is pining at his ex-lover’s house. Just one spark of attention, one sterile greeting would be enough, but unfortunately, she does not budge. Retold like this, it sounds like a tear-jerking, sentimental penny novelette. And that pitfall is avoided by Dylan’s frantic choice of words; it provokes associative side-tracks which make the text sparkle.

He stays on this track. In the following verse, “he kneels ‘neath her ceiling” and is “as helpless as a rich man’s child” In the – beautiful – bridge, the poet excels in his beloved catachrese, the ‘misuse’ that still sounds very familiar. “Like a poor fool in his prime,” does not make sense, neither does the rhetorical question “is your heart made of stone, lime or solid rock?”

The metaphors in the third verse insinuate sexual allusions, but more than ambiguous suggestions they are not really. Many commentators lose themselves in nudge-nudge-wink-winks with regard to the velvet door. Recognized and high-quality Dylanologist Andy Muir knows that the window and the velvet door are “well-known blues metaphors for sexual apertures”, Clinton Heylin mentions it as an example of sexual innuendo and dozens of other Dylan exegetes cheerfully parrot it.

Baseless; a “velvet door” really is nowhere to be found in the blues canon or in the literature – sexual associations are obvious, indeed, but more appropriate is the interpretation that the poet plays with our associations here – the metaphor for someone who is soft on the outside and appears to be accommodating, but turns out to be hard and rigid. Also matches what is revealed to be behind that velvet door: a scorpion crawling across the floor.

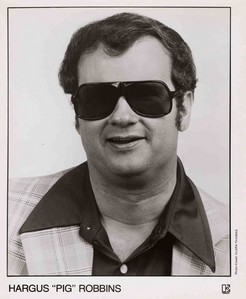

Musically the song is a well-chosen resting point between the driving dynamics of “Most Likely You’ll Go Your Way” and “Absolutely Sweet Marie”. “Temporary Like Achilles” is carried by the clattering playing of the blind pianist Hargus “Pig” Robbins, and that alone distinguishes the song from the other pieces on Blonde On Blonde. It starts out like a traditional blues, but surprises halfway with an unusual tone change; not only does a middle-eight create an alien atmosphere in such a classic blues, the choice for minor chords is also unexpected. Normally the musician slides down to seventh chords. Unusual, but certainly very successful – thanks also to the beautiful melody. Though Dylan does not share that opinion, apparently. It is, bizarre enough, the only song from Blonde On Blonde he will never play and will be left without looking back (even the Sad-Eyed Lady is rehearsed once, in 1975).

Also from the amount of covers it can be deduced that “Temporary Like Achilles” is indeed the wallflower of Dylan’s most sparkling masterpiece, snowed in by all the beauty around it. Undeserved, of course – on an album by any other artist, this song would be the prom queen.

Amusing is the pleasantly swinging New Orleans approach of the rather obscure Don Olson Gang (2006). The neat version of a veteran, the gifted blues guitarist Deborah Coleman on the tribute album Blues On Blonde On Blonde, is spotless but not very exciting. And music magazine Mojo, which is initiating a sympathetic birthday project at the fiftieth anniversary of the LP, also has no surprise. On the CD that is filled with more and less successful, but in any case remarkable covers of all fourteen songs, “Temporary Like Achilles” stands out in a negative way; the stale, amateurish living room recording by the moderately talented Kevin Morby bores after just twenty seconds. Forgive him; there are very few Blonde On Blonde covers which do not collapse under the weight of the original.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/629/Temporary-Like-Achilles

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box.