by Jochen Markhorst

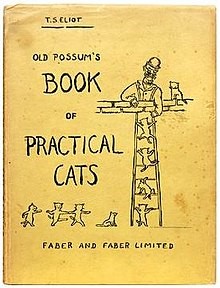

In November 2015, Andrew Lloyd Webber is considering adding yet another cat in a next revised version of Cats, one of the most successful musicals of all time. The musical is based on T.S. Eliot’s playful Old Possum’s Book Of Practical Cats, a collection of poems about a dozen cats and their lives. Originally, Eliot wrote the verses in letters to his godchildren and, as it turns out, sometimes also to friends. The compilation of those poems, in 1939, becomes a success.

The consideration of Andrew Lloyd Webber is due to the discovery of an as yet unknown poem about an as yet unknown cat, in a recovered letter from 1964, a letter of thanks from T.S. to his friend Anthony Laude for a dinner at his home. In it he also expresses his admiration for Anthony’s cat, the “particularly fastidious eater” Cumberley, a “dignified and beautiful cat”, whom he then honours with a nice ode on “Cumberleylaude”, a “gourmet cat” who enjoys life’s little joys:

The gourmet cat was of course Cumberleylaude,

Who did very little to earn his dinner and board,

Indeed, he was always out and about,

Patronising the haunts where he would find,

People are generous and nice and kind,

Serving good food to this culinary lout!

With care he chooses his place to dine,

And dresses accordingly, if he has time,

Tasting all that Neville Road offers,

With never a thought for anyone’s coffers!

The best is only fit for the best he opines,

When he wants salmon, or duck, or expensive French wines.

Witty, elegant, and clearly just a scribble; Eliot would undoubtedly have repaired the crippled meter for Old Possum’s Book and probably also added a few stronger rhymes. Remarkable, however, is the antique-looking but fresh rhyme scheme, a rhyme scheme that one will not find anywhere in the world literature: aab-ccb dd-ee-ff.

Not anywhere? Well, one single time, almost perfectly: in “No Time To Think”, Dylan’s verbose masterpiece on Street Legal.

In printed form, in Lyrics and on the site, the text is presented in eighteen four-line verses and thus it is not immediately noticeable:

In death, you face life with a child and a wife

Who sleep-walks through your dreams into walls

You’re a soldier of mercy, you’re cold and you curse

“He who cannot be trusted must fall”

Loneliness, tenderness, high society, notoriety

You fight for the throne and you travel alone

Unknown as you slowly sink

And there’s no time to think

… but it is after rearranging the words like Dylan sings them:

In death, you face life

with a child and a wife

Who sleep-walks through your dreams into walls

You’re a soldier of mercy,

you’re cold and you curse “He

who cannot be trusted must fall”

Loneliness,

tenderness,

high society,

notoriety

You fight for the throne

and you travel alone

Unknown as you slowly sink

And there’s no time to think

The first quatrain, with those two internal rhymes, is therefore actually two terzetto’s. Exactly how Thomas Stearn Eliot in anapestic tetrameters “actually” writes tercets in his cat poem Bustopher Jones: The Cat About Town.

In the whole of St. James’s the smartest of names is

The name of this Brummell of Cats;

And we’re all of us proud to be nodded or bowed to

By Bustopher Jones in white spats!

… which, just like the officially four-line couplets of “No Time To Think”, sounds like:

In the whole of St. James’s

the smartest of names is

The name of this Brummell of Cats;

And we’re all of us proud to

be nodded or bowed to

By Bustopher Jones in white spats!

Same rhyme scheme, identical meter, equivalent inventive enjambements … if Dylan did not use Old Possum as a template, we see at least illustrated: great minds think alike.

Dylan the Poet does go one step further, though. Eliot’s cat poems remain playful and entertaining, not only content-wise, but also with regard to form, the form of children’s songs and folk songs. Dylan, on the other hand, is not only much heavier in content, but after two tercets he takes a turn to an octave, to two quatrains, thus constructing “reverse sonnets”.

And this applies to every pair of couplets: the lyrics actually consist of nine inverted sonnets – first the sestet, then the octave. The layout hides how tightly the word artist and rhyme champion Dylan adheres to that medieval-looking poetry pattern, only the recital reveals the brilliant rhyme finds. Especially those syntax-breaking enjambements of mercy / curse He in the first verse, or like in the last verse, where the reader unsuspectingly reads:

Stripped of all virtue as you crawl through the dirt

You can give but you cannot receive

… while the listener gently rocks along with:

Stripped of all virtue

as you crawl through the dirt You

can give but you cannot receive

Just like, again, T.S. Eliot lavishly infuses his Old Possum’s Book Of Practical Cats with those brilliant rhymes through enjambment:

He is equally cunning with dice;

He is always deceiving you into believing

That he’s only hunting for mice.

He can play any trick with a cork

Or a spoon and a bit of fish-paste;

If you look for a knife or a fork

And you think it is merely misplaced

(Mr. Mistoffelees)

… or:

Gus is the Cat at the Theatre Door.

His name, as I ought to have told you before,

Is really Asparagus. That’s such a fuss

To pronounce, that we usually call him just Gus.

(Gus: The Theatre Cat)

… with which both Dylan and Eliot demonstrate being soulmates of the grandmaster Cole Porter, who constructs even more extreme hyphenations to rhyme weirdly naturally:

When ev’ry night the set that’s smart is in-

Truding in nudist parties in

Studios.

Anything goes.

And

When Rockefeller still can hoard en-

Ough money to let Max Gordon

Produce his shows,

Anything goes.

Wonderful, sparkling and skilled finds. But here too: Dylan’s “No Time To Think” is more ambitious. Reversing the classic Petrarcan sonnet is already an original trick, strangely enough. Although dozens of sonnet variants have been conceived since Petrarch, the reversal of octave and sestet actually never occurs. Rilke sometimes comes close and Dante also does something similar twice (but then writes two sestets, followed by an octave). Both times, incidentally, in the collection La Vita Nuova, the anthology that is a candidate for that famous “book of poems” that is “written in the soul” of the narrator in “Tangled Up In Blue”.

And it doesn’t stop there; the industrious Dylan strings together no fewer than nine sonnets, and in fact produces a complete series of sonnets for one song – quite a unique feat in song art.

Although the work idiomatically is at least as ambitious, it is less revolutionary on that particular front. Bible references, echoes of ancient mythology, unusual word combinations (so-called catachresis) and replicated fragments from old songs … T.S. Eliot’s technique, and one of Dylan’s style characteristics since the mid-60s.

Old song fragments seem to come from Cole Porter too, as the German Dylanologist and folklorist Jürgen Kloss notices in his remarkable article Rhyming With Bob (2007). A bit remodeled, but the spirit of “Let’s Not Talk About Love” (1941) leaves traces, to say the least:

No honey, I suspect you all

Of being intellectual

And so, instead of gushin’ on

Let’s have a big discussion on

Timidity, stupidity, solidity, frigidity

Avidity, turbidity, Manhattan and viscidity

Fatality, morality, legality, finality

Neutrality, reality, or Southern hospitality

Promposity, verbosity

Im losing my velocity

But let’s not talk about love

The other two verses are perked up with similar word processions (And write a drunken poem on / Astrology, mythology / Geology, philology / Pathology, psychology / Electro-physiology / Spermology, phrenology).

The impact is of course radically different. In Cole Porter’s song (first performance Danny Kaye, in the musical Let’s Face It!), the lyrics are aiming at laughter, and it succeeds in this area – this barrage of -idity’s, -ality’s and -osity’s does have a comic effect. Dylan can, obviously, not be accused thereof, of humour.

In essence, that is the criticism from many disappointed fans, Dylanologists and critics; Street Legal is “dead air”, Dylan sounds like a bad parody of Dylan, the poet overstretches, he produces empty poetry. And especially “No Time To Think” gets a bashing. One of the stupidest songs of his career, aimless abstractions, long-winded, melodically weak, just one long litany – it’s only a small selection from a garbage bag filled with hate mail and insults.

The criticism can be felt, but also demonstrates superficiality. The lyrics are elaborate, ambitious, intellectually challenging and anything but aimless. Lack of coherence, that could still be a justified reproach – but then again, that is not mentioned anywhere.

Form prevails, that much a somewhat more distant analysis seems to confirm.

In terms of content, it seems that Dylan had a kind of “It’s Alright Ma (I’m Only Bleeding)” 2.0 in mind: a slalom along eternal, universal vices, along temptations that threaten human salvation, doom prophecy wrapped in poetic images and literary beauty. By the poet who once promised “t sketch You a picture of what goes on around here sometimes. tho I don’t understand too well myself what’s really happening.”

This time he casts his artist’s gaze on the Wide World and records materialism, just like in “It’s Alright Ma”, but now with a beautiful, antique metaphor (Mercury rules you) and desperate violence (stripped of all virtue). He heralds destruction (the moon shinin’ bloody and pink is Joel’s weather forecast for Judgment Day: “The sun will be turned to darkness, and the moon to blood, before the coming of the great and dreadful day of the Lord,” Joel 2: 31), and he denounces human failures such as hypocrisy, selfishness and infidelity.

Here, and in that the disappointed do have a point, the poet sometimes opts for perhaps too cryptic wording and too misty symbolism. That fifteenth and sixteenth verse, for example (or rather: the eighth sonnet), with that bloody moon of Joel, seems to condemn human susceptibility to outer appearances and superficial pleasures. We are on our way to the Babylon girl, to the Whore of Babylon, to moral decay, and we cannot resist taking a final look at “Camille”. Camille? La Dame aux Camélias, La Traviata? Or Camille from Kerouacs On The Road? She is, after all, a woman who is repeatedly abandoned (by Dean), and who is sometimes given a final look. The canon does not offer many other Camille’s – this is a dead end.

The Biblical references in this verse (Babylon, starlight in the East, the blood moon) force the associations with the verse You turn around for one real last glimpse towards Lot’s wife, who takes a final look at Sodom, on moral decline, and therefore turns into a salt pillar (Genesis 19:26). But that is one real last glimpse on Sodom. Or does the poet here mean a glance cast by “Camille”? In that case this poet is the only one who knows the name of Lot’s housewife; the Bible reveals neither her name nor the ones of their daughters.

Enigmatic. But: what beautiful, flowing, singing verses –

You turn around for one real last glimpse of Camille

’Neath the moon shinin’ bloody and pink

And there’s no time to think

Still, this enigmatic quality is also the major pain for the disappointed. It is too much. Whereas with a masterpiece such as “It’s Alright Ma” impermeability contributes to the beauty (The handmade blade, the child’s balloon / Eclipses both the sun and moon), it stimulates resistance here – perhaps the critics perceive the chosen images as too academic, too artificial, not poetic enough:

Warlords of sorrow and queens of tomorrow / Will offer their heads for a prayer.

Well. Nobility and humility, the poet helpfully explains in the following verse. But that really does not help that much. “Warlords of sorrow”? It does not evoke an image, no. The reversal – the sorrow of warlords – would, but alas: that does not flow as nicely. And that probably demonstrates a decisive artistic argument, illustrates the poet’s art conception:

“It’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They… they… punctuate it. You know, they give it purpose.”

That’s what Dylan says in the Playboy interview with Ron Rosenbaum in November 1977 – around the same time he writes “No Time To Think”. “Words don’t interfere,” more important is how they sound. And well, yes, in that respect the poet succeeds. Warlords of sorrow and queens of tomorrow sounds wonderful and runs like a charm, indeed; a waltz, the dactyl, all those internally rhyming, assonancing o’s, the pleasant rhyme of sorrow – tomorrow … beautiful, but on a semantic level the words really stand in the way; their meaning does not contribute anything.

The words that “don’t interfere” seem, after all, not so much to have come up after a real sense of emotion or a genuine moral outrage, but rather have been picked from various sources which apparently float in the air, these days. Songs by Cole Porter, reading T.S. Eliot, and yet again pinches of Proust, by the look of it.

Dean in Kerouac’s On The Road always carries À La Recherche Du Temps Perdu throughout America as well, and from Dylan we know for sure that he has been browsing the book back and forth for more than half a century. We have seen Dylan’s fascination with lost time since the 1960s (“Don’t Think Twice”, “Mr. Tambourine Man”, “I’ll Keep It With Mine”, “Odds And Ends”), where not only an increasing “sense of Proust” can be registered, but also more and more Proust jargon and idiom is penetrating. Quite clear in late work such as “Summer Days” and “Floater”, irrefutable in Chronicles (in which Dylan hijacks entire sentences from Proust’s masterpiece).

Here, in this seventies song, the resonances are more vague still. The expression no time to think can be found twice in the Temps Perdu, for example, and all thirty-two nouns from those word processions in every second verse (memory, ecstasy, tyranny, hypocrisy, etc.) are also present in Proust’s masterpiece – including rather unusual terms such as epitome and materialism. Only a China doll is not mentioned (though abundantly clothing, porcelain, umbrellas, puzzles, painting and what-not from China). Well, the doll is maybe brought in by Chekhov then.

The only artists who risk a cover are brother and sister Gruska from The Belle Brigade, for the Amnesty International tribute project Chimes of Freedom: The Songs of Bob Dylan (2012) and that is actually a very nice version. The singing of Barbara and Ethan comes close to the magical shine of the Everly Brothers, the guitars have a Ry Cooder-like vibe, and the dry drums and the warm electric piano create a beautiful, autumnal colour – no, there is nothing wrong with the sound and the words, with The Belle Brigade.

However, the cover does not lead to a revaluation. “No Time To Think”, like most songs from the underappreciated masterpiece Street Legal, continues to shine lonely and alone in a rarely visited, forgotten corner in the cellar.

Maybe Andrew Lloyd Webber could be persuaded to turn it into a musical.

——————–

- There is an index of the songs reviewed in this series in: Dylan in Depth

And you may also enjoy a browse through

Nice article here …. unmasking yet another great mind that thinks alike, connecting the dots.

At last a meditation on this masterpiece (as a song) that makes sense. I cannot escape the notion that all negative reactions regarding Street Legal and especially No Time To Think, drove Dylan to abandon writing poetic songs for quite a while, and his decision to leave Angelina and Carribean Wind off Shot of Love has something to do with that too, I fear. Anyway, I allways thought that No Time To Think was just too deep for the shallow times of the disco age…

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/451/No-Time-to-Think

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.