by Jochen Markhorst

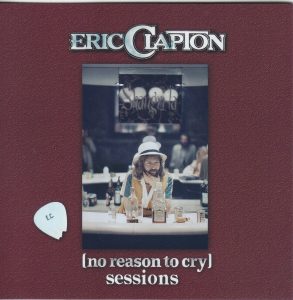

In the winter of 1975/76 Eric Clapton is in Los Angeles, in The Band’s Shangri-La Studio to record one of his most successful 70s albums, No Reason To Cry. But despite that success, he looks back with little satisfaction in his autobiography (Clapton: The Autobiography, 2007).

Clapton calls it a “drunken and chaotic album”, blaming it on his own unstable state, on the fact that he initially tried to record the album without a producer and on the idyllic location and circumstances of the studio. The men of The Band and producer Rob Fraboni come to the rescue. All Band members play along, Richard Manuel gives him the beautiful song that will be the opening song (“Beautiful Thing”) and Rick Danko writes and sings, together with Clapton, the successful song “All Our Past Times”. And above all: Slowhand is so lucky that Dylan is around, in those days.

It is a bit mysterious, by the way. Dylan “was living in a tent in the garden of the studios, and every now and then he would appear and have a drink and then disappear again just as quickly.” But during one of those brief visits from that tent-resident, Clapton can ask if the bard would contribute something to his album, “write,sing, play, anything.”

“One day he came in and offered me a song called “Sign Language,” which he had played for me in New York. He told me he had written the whole song down at one sitting, without even understanding what it was about. I said I didn’t care what it was about. I just loved the words and the melody, and the chord sequence was great. Since Bob doesn’t restrict himself to any one way of doing a song, we recorded it three different ways, with me duetting with him.”

It is, Clapton concludes this episode, all in all his favourite track on the album.

The short passage in Clapton’s memoir is intriguing. So Dylan has already played the song before, in New York. That must have been during those chaotic, overcrowded Desire sessions, to which the British guitar god has less pleasant memories. When he is invited, he is delighted, but the enthusiasm immediately evaporates when he enters the studio.

There are “two or three bands already waiting to go into the studio”, there are twenty-four musicians present and Clapton is one of the five invited guitarists. It is “not unlike being in a doctor’s waiting room” and he has the same feeling as when he first met Dylan in the mid-60s: “I felt like Mr. Jones again ”- with the witty self-mockery in which his autobiography excels, Clapton refers to the incomprehensible, disorientated Mr. Jones from “Ballad Of A Thin Man”, something is happening here, but you don’t know what it is.

Despite all self-mockery, he does ignore the parallels with his own No Reason To Cry; according to the liner notes no fewer than forty (!) people are involved in the production thereof. In addition to the names of the men from The Band and Dylan, Ron Wood also stands out – according to tradition, Clapton was first offered “Seven Days”, but he passed that song on to the Rolling Stone, who indeed plays it on his next solo album (Gimme Some Neck, 1979).

The other intriguing point concerns Dylan’s own lyrics and genesis analysis: written down in one sitting without even understanding what it was about.

That seems a bit posed. It is not that complicated. Apparently a moderately inspired Dylan wanted to unleash his creativity on the potentially fertile, symbolic sign language metaphor. In song art, and in the arts at large, a rather unexplored image, indeed, that invites the creation of Nobel-worthy new poetic expressions.

Sign language, for example, beautifully depicts the limits of the human deficit, or is the key to deciphering what is not being said; thus beautifully symbolizes the inability and pitfalls of interpersonal communication – all angles which could infuse a language-loving, poetic genius like Bob Dylan in his usual form to an “Idiot Wind” or a “Man In The Long Black Coat”.

But he cannot reach those heights, in these days. We are on the eve of 1976, a year like 1972 and like 1984, years in which the spring is dry and the poet is watching the river flow, contemplating unreachable masterpieces.

Dylan has the phrase sign language, scribbles some rhymes in the margin, of which only sandwich and advantage survive, and even these rhymes he cannot squeeze in without hammering and prying:

You speak to me in sign language,

As I’m eating a sandwich in a small cafe

At a quarter to three.

In itself a promising, cinematic opening. Similar to the decor and the constellation of “Love Is Just A Four-Letter Word” or the interlude of “Highlands”, and it seems to be based on Sinatra’s “Only The Lonely” (Each place I go only the lonely go / Some little small café) and on Sinatra’s “One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)”: It’s quarter to three / There’s no one in the place ‘cept you and me – both can be found on the album Sings For Only The Lonely (1958), incidentally.

So: in three short lines an I-person and relationship stuff, a promising metaphor, the contrast of a banal act with a universal, human conflict, an attractive, Dylan-worthy rhyme find and references to the Great American Songbook … the way seems to be paved for a multi-coloured , mosaic-like Dylan classic.

The second verse does not really destroy hope;

But I can’t respond to your sign language.

You’re taking advantage, bringing me down.

Can’t you make any sound?

… does, however, lead to a first raised eyebrow. “You’re taking advantage”? The main characters, presumably love partners, have a communication problem, the click is no longer there, they no longer understand each other – that much is clear. But apparently the poet pertinently wants to paste the rhyme find sign language / advantage into it, even at the expense of a storyline, whether intended or not. After all, this is the poet who repeatedly defines his understanding of song art with the words: it’s the sound; words should not interfere.

Dylan does not succeed here in the latter; the content of the words “taking advantage” does interfere, is alienating and distracts from the sound.

The poet, who told Clapton he shook the lyrics out of his sleeve in one short session, recognizes this too. The third verse is therefore not very ambitious:

‘Twas there by the bakery, surrounded by fakery.

This is my story, still I’m still there.

Does she know I still care?

… a lazy, empty rhyme (bakery / fakery), a stylistic remarkably weak line of text (This is my story, still I’m still there) and a weirdly unsuccessful punchline, where the I-person suddenly becomes sentimental and – out of nowhere – wistfully wonders if she knows he still cares about her.

No, this is not the song artist who wrote “Abandoned Love” barely six months ago and who will build an alphabetical cathedral like “No Time To Think” in a year and a half.

Some rehabilitation then the final verse offers.

Link Wray was playing on a jukebox, I was paying

For the words I was saying, so misunderstood.

He didn’t do me no good.

The rhyming triple is nice and a pre-announcement of the rhyming pleasure that Dylan soon will demonstrate on Street Legal (“I took a chance, got caught in the trance or a downhill dance” in “We Better Talk This Over”, for example) and the greeting to Link Wray is appealing. Link Wray is thus admitted to a fairly exclusive members’ club, the club of Musicians Who Are Mentioned In A Dylan Song.

Neil Young, Alicia Keys, Blind Willie McTell, Ma Rainey and Beethoven, Billy Joe Shaver, Elvis … it’s a colourful, attractive mix of people and Link “Rumble” Wray will feel at home there. And apparently the name check also contributes to his already undisputed status; after Dylan, Link Wray is also sung by The Fall (“Neighborhood Of Infinity”, 1984), The Who (“Mirror Door”, 2006) and by Robbie Robertson (“Axman”, 2011).

With a sense of poetry, one might appreciate Robbie Robertson’s tribute to Link Wray as the closing of the circle; after all, Robertson plays two solos in that first homage, in “Sign Language”. Wonderful, again – it varies on that unusual, pinched, nervous little tour de force opening Dylan’s “Going, Going, Gone” on Planet Waves. Which is again very gracefully and sympathetically appreciated by Clapton, who is actually a much better guitarist:

“It also gave me the opportunity to overdub Robbie Robertson, doing his “wang bar” thing that I love so much.”

He is elegant, the godly Commander Of The Order Of The British Empire, triple member of the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, West Bromwich Albion fan and eighteen-fold Grammy Award winner from Ripley, Surrey.

Eric Clapton with Bob Dylan:

Sign language

She wants to hear sweet words, but he stays silent, because he will not lie.

“’Twas there by the bakery

Surrounded by fakery”

“At a quarter to three” he hears the sound of silence, and at that moment he knows: The end is near.

Here is a sugar sweet sound about the same problem. It is a reflective song – not a song about exactly THAT moment, where he knows it is all over.

Frank Sinatra: My way

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6E2hYDIFDIU

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

http://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/565/Sign-Language

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.

I think that the Sing Language lyriccs are a little spare, but they are still very precise and poignant. What is more, the quiet lyrics make Robbie Robertson’s signature guitar stand out in relief. That goes double for Garth Hudson’s organ. The Band lived on here. The whole thing is a very beautiful procession, in my opinion.