by Jochen Markhorst

Searching for a gem, looking for a jewel, as Dylan sings in “Dirge” and that is a well-found song quote for searchingforagem.com, the site that tries to bring order to the endless ocean of oddities and obscure Dylan releases.

The same sense of romance is evident from the name for the double album Nuggets, gold clumps, which Elektra releases in 1972, a compilation album on which obscure songs by obscure, mostly psychedelic bands from the period 1965-1968 are being saved from oblivion.

The unexpected, great success of the record indeed brings about a revaluation for some of the polished nuggets. For the band of Dylan’s organist Al Kooper, for example, The Blues Project, whose “No Time Like The Right Time” closes side 1. This does Al Kooper a kind of poetic justice; after all, the pop music-loving world owes him the retrieval of Odessey & Oracle, the Zombies’ masterpiece that only is released after the band has already disbanded itself due to a lack of success. “Time Of The Season” is the big hit, in 1969, two years after the Zombies recorded it.

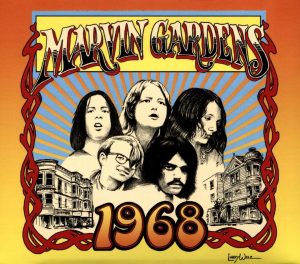

The mine from which those lost gems are dug up, has since seemed inexhaustible. Not all excavations really deserve that delayed appreciation, but every once in a while: bull’s eye. In November 2016, 1968 is released, from the completely unknown Marvin Gardens. The band, from San Francisco of course, is mainly driven by the boundless talent of Carol Duke, a cross between Janis Joplin and Grace Slick. The Texan (from Lubbock, the birthplace of Buddy Holly) has the blues and folk in her blood, and that blends well with the psychedelic rock of her Californian brethren. The band dares to polish and beautify great songs from Leadbelly, Mississippi John Hurt and Hoagy Carmichael, and has own material too, but their piece de résistance is a Dylan cover: the lost ditty “Walking Down The Line”.

It is one of Dylan’s early railroad songs. From the very beginning, the construction of the first railways is idealized with big words like “connecting people”, “progress”, “unification” and “prosperity”. And rightly so, of course. In the Arts, however, the endless strings of steel soon symbolize Wanderlust, the romantic longing for unknown destinations and, strangely enough, demise, loneliness and abandonment too.

The train is a tragedy proclaiming leitmotif in Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina (1877), in 1843 one of Dylan’s heroes, Nathaniel Hawthorne, chooses the railroad as a metaphor for the spiritual journey his protagonist makes (The Celestial Railroad), in almost half of all stories of another hero, Chekhov, trains come by, Melville often uses train imagery and the first filmmakers also recognize the dramatic power of a railway set (such as The Kiss In The Tunnel, 1899, and The Great Train Robbery, 1903).

Dylan is, as is well known, fond of the symbolic power of train transport and, at the very least, taken with the misty ambiguity that arises when allowing a roaming protagonist to walk down the line. After all, apart from walking along the railway line, it can also mean: going over a straight line to prove that you are not drunk, balancing on the border between Good and Evil, or staying good, walking in line. That last meaning is the meaning that the main character in Johnny Cash’s “I Walk The Line” expresses, and that particular song Dylan has had almost his entire life on a towering pedestal, as we understand from his autobiography Chronicles when he talks about his song “Man In The Long Black Coat”:

“In some kind of weird way, I thought of it as my “I Walk The Line,” a song I’d always considered to be up there at the top, one of the most mysterious and revolutionary of all time, a song that makes an attack on your most vulnerable spots, sharp words from a master.”

This walk the line echoes considerably with the young Dylan. Alone in those early years he uses the expression in “Mixed Up Confusion”, “Bob Dylan’s Blues” and in “Restless Farewell”. And in “Walkin ‘Down The Line”, a remarkable song that of course does not have the mythical power of Cash’s masterpiece, but which also makes a fair impact.

Part of the attraction lies in the stimulating contrast between lyrics and music. The storyteller, who is dragging down the line, is certainly not happy. He has walked all night along the rails, melancholic, with a troubled mind, his girlfriend, who by the way is not too smart, is not feeling well and the money has run out. Sadness everywhere, but the musician Dylan lays a catchy, cheerfully hopping melody underneath, which gives the lament (unintentionally?) a comical charge.

The decor cannot be determined unambiguously. But his feet are flying and he is wearing his walkin’ shoes, so it is likely that the poet here tries to evoke the image of a destitute wanderer following a railroad. The poet has not given much love to the lyrics. It is also figuratively a directionless whole, a not too inspired collection of folk and blues clichés, with just one single Dylan-worthy flash: I see the morning light / Well, it’s not because / I’m an early riser / I didn’t go to sleep last night.

Dylan considers the song a throw-away, apparently, and treats it that way. To safeguard copyrights, he makes a Witmark recording (which will later end up on The Bootleg Series 1-3), for Broadside Dylan already recorded it once before, in October ’62, and in May ’64, at colleague Eric Von Schmidt’s home in Florida, it surprisingly pops up again, but it never reaches a stage or an album.

https://youtu.be/v4z3w8tVxoU

However, the song does not go unnoticed either. It is immediately picked up by colleagues and covered dozens of times in the 60s alone. The narrator’s suffering completely evaporates in all those cheerful, hopping arrangements, but that does not spoil the fun; the melody and the accompaniment have such indestructible, granite power that every adaptation is contagious.

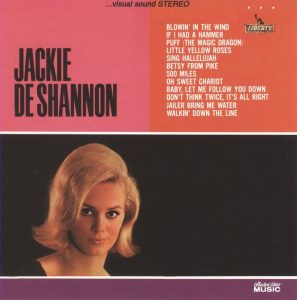

The first one is recorded as early as 1963 and is done by the very charming and very talented Jackie DeShannon. It opens her debut album, which she originally wanted to fill with Dylan covers. Remarkable, because this is shortly after The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan; Dylan’s repertoire is by no means the inexhaustible treasure trove it will be a few years later. DeShannon’s record company Liberty, however, puts a stop to the intention and the singer has to limit herself to three Dylan songs (“Blowin ‘In The Wind” and “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right” survive too), accompanied by folk classics such as “500 Miles” and Dylan related songs such as “Baby Let Me Follow You Down”.

No own songs, by the way, and that is quite remarkable. DeShannon has written dozens of excellent songs. “Put A Little Love In Your Heart”, “Bette Davis Eyes”, “When You Walk In The Room”, “Breakaway”, to name just a few, and her songs are often covered. “Don’t Doubt Yourself Babe” on The Byrds’ first LP Mr. Tambourine Man is hers, for example, as well as Marianne Faithfull’s biggest hit “Come And Stay With Me”. But for her first album she does not dare to do her own work, oddly enough – or those fools from Liberty intervened again, which is of course a possibility too.

Anyway, the gifted songwriter acknowledges and recognizes Dylan’s mastery early on.

Other covers from this period all have a similar, dated sound and arrangements (Glen Campbell, The Dillards, Joe & Eddie, Ricky Nelson), without undermining the song’s charm.

“Walkin’ Down The Line” continues to be popular in later decades. Sometimes to boost a performance (Linda Rondstadt, for example), sometimes as an attractive option to fill up an album side (Ry Cooder with the Rising Sons, Eilen Jewell) and very occasionally on Dylan tribute records (the one by Robin & Linda Williams on A Nod To Bob Vol.2 from 2011 is great fun). In 1987 it seems that Dylan is finally giving in. The men of Grateful Dead want to play the song on their joint tour. It is even practiced, the recording thereof reveals a very pleasant, energetic version and Dylan seems to like it too – but ultimately rejects it again.

In the end, the most beautiful version is that excavated jewel from 1968 of the late revelation Marvin Gardens. The intro is goose bumps inducing, the arrangement fluctuates somewhere between The Who and The Doors, and is infinitely more intelligent and varied than the bulk of those dozens of other covers. But above all: it is one of the few interpretations where the interpreter respects the lyrics’ content. Singer Carol Duke and the band understand that they need to express the suffering of a bumped soul, walkin’ down the line with a troubled mind.

Thanks for PART 2…

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/714/Walkin-Down-the-Line

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.