by Jochen Markhorst

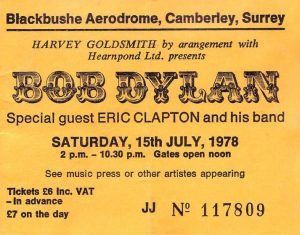

Nuremberg, July 1 1978. Bob Dylan offers Eric Clapton a cassette with the first two songs he wrote with Helena Springs: “Walk Out In The Rain” and “If I Don’t Be There By Morning”. Two weeks later Clapton already has recorded both and can present his adaptation to Dylan and Springs when they meet again, this time in England (Blackbushe Aerodrome, July 15). Dylan’s performance there also inspires the title of the album on which the songs will open side A and side B respectively:

“The album we were promoting on this tour was the follow-up to Slowhand, which we had named Backless, a title suggested after we played a gig with Dylan at Blackbushe Airport. It referred to the fact that I thought he had eyes in the back of his head and knew exactly what was going on around him all the time.”

(Eric Clapton, The Autobiography, 2007)

Thus Dylan leaves his mark on this LP on several fronts. But he does not get much applause; both songs are not much appreciated in Dylan circles, and generally “If I Don’t Be There By Morning” is dismissed as even weaker, or more uninspired, or more meaningless than Walk Out. Clapton himself, however, loves the song. It is released as a single (and flops), the song is on his set list for two years, 44 times, and one of those performances also earns a place on his successful live album Just One Night (1980).

In later years, a modest, yet public, revaluation takes place. Just like with Walk Out: Time is friendly for the song. In retrospects and discographies the song is usually ignored, but sometimes it is appreciated as a “pleasant rocker”. The “chunky riffs” get compliments and the song “generates some excitement” because Clapton sounds like The Band.

The revaluation is justifiable. It really is a very nice, melodic rocker, the bridge is remarkable and true, the lyrics are not too titanic, but still food for Dylanologists; largely Love and Theft, so the song uncovers some of the master’s influences and fondnesses.

Dylanesque it is, except for that weird bridge. Both the melody and the words of the bridge are atypical, and especially on a lyrical level suspiciously weak:

Finding my way back to you girl, Lonely and blue and mistreated too. Sometimes I think of you girl, Is it true that you think of me too?

Song titles can sometimes start with a gerund. “Watching The River Flow”, “Driftin’ Too Far From Shore”, “Standing In The Doorway” and “Seeing The Real You At Last”, for example. But within the lyrics it soon gets juvenal and Dylan hardly ever starts a verse with it. “Jokerman”, “Roll On, John” and “Temporary Like Achilles” are the exceptions – and within these songs, they are also the literary weaker spots.

In these song lyrics it doesn’t get any better after Finding, with the poor, Dylan-unworthy rhyming by repetition and the hollow cliché lonely and blue as outliers.

The similarity with the hit song “Working My Way Back To You” by The Four Seasons is probably a coincidence; that was a small hit in the spring of ’66. The worldwide mega hit version by The Spinners is a 1980 release.

The other couplets are much stronger, fortunately. The opening line, Blue sky upon the horizon, is an original and confusing stage direction, suggesting either the beginning of the day or the end of dark clouds at the same time. After that the poet Dylan assembles a blueslamento from various sources.

Blue sky upon the horizon, Private eye is on my trail, And if I don't be there by morning You know that I must have spent the night in jail

Heylin points to Grateful Dead’s “Friend Of The Devil”, the song that Dylan himself will play almost a hundred times between 1990 and 2007. The Dead sings about a sheriff on my trail, Dylan about a private eye on my trail, which rhymes with jail in both songs, and both protagonists remember a twenty dollar bill.

In the live performances of “Going, Going, Gone” in these summer months of ’78 it is already noticeable that Dylan smuggles in a complete verse from Robert Johnson’s “From Four Until Late”, and in this song an echo seems to resonate, too. Johnson opens the second verse with From Memphis to Norfolk, in this song Dylan turns it into, also as opening of the second verse, from Memphis to L.A.

Similarly, Leadbelly resonates in Dylan’s discography since his very first steps in a studio (“Midnight Special”, “Corrina, Corrina”). Fragments from Leadbelly’s songs have coloured Dylan’s work for at least as long; “Gallows Pole” in “Seven Curses”, “John Hardy” in “John Wesley Harding” and “Mr. Tom Hughes Town” (or “Fannin Street”) echoes in both “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and “The Groom’s Still Waiting By The Altar” (Shreveport women gonna kill you), to name only three examples.

From that last song again seems, equally unimportant by the way, to descend a next phrase: I got a woman living in L.A. versus I got a woman living on Stone Hill.

Interesting, though not too important, all of this, and not very revolutionary either, but it does suggest that, as with “Stop Now”, for example, Helena Springs’ input is very limited. Grateful Dead, Robert Johnson, Leadbelly… all of them artists who are under the skin of the seasoned bluesman Bob Dylan – it is quite unlikely that, while talented, the young, green girl Helena Springs could shake all those references and paraphrases out of her puff sleeve.

It also applies to the title and vers line If I don’t be there by morning. Grammatically and/or syntactically incorrect (it must be either “if I am not there” or “if I won’t be there”). A weathered songwriter like Dylan effortlessly ignores language errors for the sake of rhyme and reason, but an inexperienced novice would not dare to let it pass (according to her own words, this is Springs’ second song lyrics attempt).

The limited input perhaps explains those wondrous additions to the Dylan / Springs songs in the Copyright Files:

With this document, signed by Helena Springs, the songwriter transferred and assigned to Special Rider Music “all her right, title and interest,” including the copyright

… and under “Notes” the whole is once again defined as an “Assignment”, so as a transfer. The same goes for those other songs that have been officially released, such as “Coming From The Heart”, “Stop Now” and “Walk Out In The Rain”.

Agreed, sometimes the songs with co-authors also get strange additions. As with “Isis,” from which Jacques Levy is said to have a 35% ownership:

words, music & arr.: Robert Dylan p.k.a. Bob Dylan;

words: Ram’s Horn Music, as employer for hire of Jacques Levy.

… but there is no such addition like this “the rights have been transferred” – though “as employer for hire” is odd again.

The rights to songs he writes with Robert Hunter, like the horrible “Ugliest Girl In The World”, are properly registered to both Ice Nine Publ. Company, Inc. (Hunter’s, or rather Grateful Dead’s publisher, of which Hunter is the president) and to Dylan’s Special Rider Music. Just as, for example, the collaboration with Michael Bolton, “Steel Bars”, is unsurprisingly in both names (Mr. Bolton’s Music, Inc. and Special Rider Music), like “Got My Mind Made Up” is also registered to Tom Petty’s company Gone Gator Music and the honour and rights for “Under Your Spell” are shared with Carol Bayer Sager Music.

In short, it is quite unusual for a co-author to be requested to transfer all rights to Dylan’s music publisher. Springs may still share in the royalties, but it is more likely that she has sold her rights – the U.S. Copyright Office reports on all songs that Dylan’s Special Rider Music is the only “Copyright Claimant”, the only entitled party.

Peculiar. But all that legal haggling has no further influence on the impact of the song, obviously.

That impact is negligible. Just like almost all songs from the Street Legal period (apart from “Señor”), “If I Don’t Be There By Morning” drifts unnoticed away on the Waters of Oblivion. In 2001, the Louisiana veteran club The Hoodoo Kings produces a nice but rather superfluous cover on their eponymous album (although the JazzTimes of July 1, 2001 considers the interpretation as one of the four highlights of the album).

Already in ’78 the Flemish singer Ann Christy tries to score a hit with the song, remarkably enough in combination with that other Dylan / Springs / Clapton title, “Walk Out In The Rain”. Fans of the late Christy think to this day that Dylan wrote the songs for her – and both readings were then, and still are, insurmountably frumpy.

The best interpretations are and remain the live performances of Mr. Slowhand himself. But even Clapton never plays “If I Don’t Be There By Morning” again after May 18, 1980.

In Guildford by the way, 15 miles from Blackbushe Aerodrome – so before abandoning her, he does take the song back home, like a gentleman. Well before the morning, of course.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/288/If-I-Dont-Be-There-By-Morning

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.