by Jochen Markhorst

They may be a bit awkward and bewildering sometimes, but more often they are touching still, the advertising miniatures Dylan occasionally lends himself to in the twenty-first century. The Pepsi commercial is slick, sweet and not very subtle, but actually gives a giant respectful and fun upgrade to “Forever Young”, thanks also to Will.i.am. The sober Apple advertising for the iPod and iTunes from 2006 (with “Someday Baby”) is contagious and stylish, and the film in which Dylan drives through an empty landscape in a Cadillac Escalade confirms the words of Liz Vanzura, Cadillac’s marketing director of: “We tried to be very respectful of the fact that he’s a legend.”

That succeeds partly because the bard, as in those other commercials, says nothing qualitative about the product to be praised. And because Pepsi, Cadillac and Apple are true Americans, just like Dylan, with some tolerance and repression of overly critical thoughts one could suspect Dylan’s recommendation is truthful.

Perhaps because the master talks more, this is a bit more difficult with the IBM advertising. But then again the words of the talking computer Watson fascinate, claiming to have analyzed all of Dylan’s songs.

“Your main themes are,” Watson concludes, “Time Passes and Love Fades.”

“That sounds about right,” Dylan replies amused.

Watson’s claim is actually about right. IBM spokeswoman Laurie Freedman officially reports that the researchers really have fed 320 Dylan songs to Watson and his analysis truly has distilled the aforementioned themes. Wilson’s capabilities of “personality analysis, tone analyzer and keyword extraction” has helped to better understand the data.

Granted, 320 is not all songs, but still: more than half.

The appreciation for Dylan’s commercial trips is anything but widely shared. The fact he allowed the Bank Of Montreal in 1996 to use “The Times They Are A-Changin”, already did taste a bit tricky, but could at least still be classified under the safe heading ‘Irony’. That escape is less credible with the first time that Dylan also physically features in a product promotion, for Victoria’s Secret in 2004. Only the seasoned connoisseurs smile, because they immediately remember the giggly 1965 press conference:

Q: Mr. Dylan, Josh Dunson in his new book Freedom In The Air implies that you have sold out to commercial interests and the topical song movement. Do you have any comments, sir?

BD: Well, no comments, no arguments. No, I sincerely don’t feel guilty.

Q: If you were going to sell out to a commercial interest, which one would you choose?

BD: Ladies’ garments.

Lo and behold! A Biblical forty years earlier the Prophet is already announcing his appearance in a lingerie advertisement.

The song chosen for the soundtrack is “Love Sick” and thereby Dylan casts a second shadow over the beauty of the song.

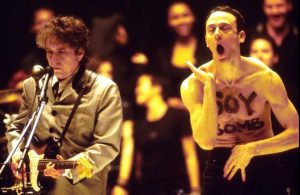

Dylan cannot be blamed for the first Great Distractor. At the presentation of the Grammy Awards in 1998, where he picks up his three Grammies for Time Out Of Mind, Dylan plays “Love Sick”. During the performance one of the background dancers breaks loose, uncovers the upper body, on which with large letters Soy Bomb is written, and performs a somewhat spastic-looking dance right next to Dylan, until he is removed.

The man is a self-proclaimed performance artist, one Michael Portnoy. The purpose of his disturbance was, as he explains later, to “send positive vibrations to viewers at home.” The words soy bomb are a poem that he, on request, also is willing to explain: “Soy… represents dense nutritional life. Bomb is, obviously, an explosive destructive force. So, soy bomb is what I think art should be: dense, transformational, explosive life.”

That crystal clear message did not completely come across. Portnoy blames this, somewhat regretfully, on a miscalculation: “Soy bomb was intended to be a simple poem, but my arms stole all the attention.”

It does, however, draw continuing attention to Portnoy, unfortunately. He is allowed to make his fuzzy say in all major newspapers, gets a stage for his, presumably meant ironically, but still utterly infantile croaking (“Bob Dylan is a thing of the past, I am the future of music” – Daily News) and even true artists like pop artist Eels sustain the stolen fame (“Whatever Happened To Soy Bomb” on Blinking Lights And Other Revelations, 2006).

All in all, the squabbles overshadow the beauty of Dylan’s performance and the extraordinary power of “Love Sick”. On the bonus DVD with the Limited Edition of Modern Times (2006), Portnoy is flawlessly cut away and the glory is artificially restored.

The second Great Distractor is the use of the song in that Victoria’s Secret commercial. Featuring top model Adriana Lima, dressed as sparse as Portnoy at the time, but much more attractive, obviously. The clip offers hardly a story. Lima squirms and seduces, an unaffected Dylan throws, a little surly, his hat on the floor and leaves again, Adriana puts on the hat. There is the connection to the soundtrack: apparently the man does not desire love – perhaps he is sick of love.

The stylized aesthetic of the images certainly detracts from the raw splendor of the song itself. As the opening track for the album, it may be an equally remarkable choice (as the conclusion of an album full of decline and deterioration, it seems more appropriate), but it is actually a great introduction as well.

Producer Daniel Lanois deserves praise. The the first six seconds of the album is rudderless sounds, studio buzz, musicians sitting down with their instruments, or something, then the staccato organ hits from Augie Meyers (“that little back beat skank organ,” as Lanois calls it pleasantly disrespectful) and then that wonderful sound of Dylan’s singing. As if he is calling from an old telephone booth somewhere along a deserted Arizona road to the studio in Miami.

It is a wonderful find from Lanois; by disconnecting the singer from the song, from the recording, as it were, he prevents the song from becoming larmoyant, he avoids it becoming an embarrassing exposé of self-pity and exaggeration. Recorded this way, the despondent words of the washed out narrator get the stately opulence of a nineteenth-century symbolist. “I’m walking through streets that are dead”, “weeping clouds”, “you destroyed me with a smile”, “silence like thunder” … old-fashioned imagery that could have been produced by a fellow Nobel Prize winner like pessimist Maurice Maeterlinck (1862-1949) ) or Baudelaire (“The sound of music, tormenting and caressing / Resembling the distant cry of a man in pain”). But the direct inspiration comes from the Bible again, this time from the Song of Songs: “I am sick of love” is literally there (5:6).

The simple but compelling pulse of the song is just as tempting – the song is popular with colleagues. The well-known contribution of Mariachi El Bronx to the Amnesty project Chimes Of Freedom (2012) eases the angularity of the original and also has a distinctive arrangement (Mexican trumpets, abundant percussion and kitschy gypsy violins). Really appropriated, though, the song is by The White Stripes; “Love Sick” is about a hundred times on the set list and Jack White brings it so intense, loving and driven, that a whole generation of fans thinks it is actually a Jack White song.

In terms of intensity, however, that version is (more than) surpassed by our Flemish friends from Triggerfinger. Ruben Block opts for a similar voice distortion and a similar arrangement as the original, but the performance of the three-man band is – of course – even more meager. And therefore perhaps even more desperate and ominous than Dylan’s. It is definitely the most beautiful cover, and one that may stand next to the master himself.

Worth mentioning, hors concours, is the rendition by one of Dylan’s maternity assistants, an assistant who contributed to the original version: Duke Robillard, one of the guitarists on Time Out Of Mind. Robillard is a veteran (born 1948) and a versatile blues guitarist who seems to mature with the years; especially since the 90s, his popularity among colleagues has been flourishing and he is increasingly being asked for session work. In between, he makes meritorious solo albums, dozens by now, on which the same respect for tradition can be heard as on Dylan’s later albums. New Blues For Modern Man (1999), the album he records shortly after his work with Dylan, presents in addition to his interpretation of “Love Sick” also an admirable cover of Charley Patton’s “Pony Blues” – probably not by chance one of Dylan’s great loves. Robillard’s “Love Sick” is a very pleasant, soulful and sultry homage. His singing skills are not too heavenly, unfortunately, but the rest is masterful. Particularly his B.B. King- and Snowy White-like guitar work.

Wonderful article. Very articulate! Must get out my dictionary to double check some of it. But, hey I enjoyed it and the sounds of Love Sick you also provided. More please and thanks for this.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/387/Love-Sick

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.