by Jochen Markhorst

The Fleet Foxes, a most charming band from Seattle, has been playing in the Premier League since 2008. Pillars are craftsmanship, catchy melodies and especially music historical awareness: the comparisons with the Beach Boys, Van Morrisson and Crosby, Stills & Nash all make sense.

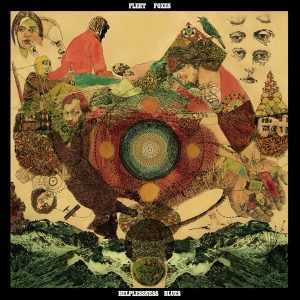

A crown on the love for homage appears in 2011; on the second album Helplessness Blues is “Lorelai”, a wonderful rip-off from Dylan’s “4th Time Around”. This places the Foxes in a beautiful tradition. Just as Dylan himself does so often, they reuse an existing melody (with small shifts) and that is especially fitting for this song: “4th Time Around” is already a recycled homage to an earlier song: to “Norwegian Wood” by The Beatles – again Lennon’s attempt to write a Dylan song. “Everything’s stolen or borrowed,” are the appropriate closing words of “Lorelai”.

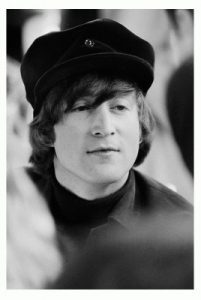

There has been some fuss about this Beatles connection, over the years. Dylan lays a template on Lennon’s “Norwegian Wood”, that is the general agreement by now. Still, the question remains as to what motives Dylan has. Is it intended as a homage or as a parody? Or, in fact, as a kind of warning? Lennon cannot figure it out either. In ’65 the band members often tease him with his Dylan fascination and in his more paranoid moments he thinks Dylan is now cynically reproving him (particulary the closing lines about some personal crutch which the you is not supposed to use, indicating: “don’t try to copy me,” as one might understand), in other interviews he sees it as a friendly nod. Anyway: Lennon will never wear his Dylan cap again, after “4th Time Around”.

Nevertheless, even after songs like “I’m A Loser”, songs that Lennon acknowledges being influenced by Dylan, the bard from Hibbing remains a regular guest.

The reference in “Yer Blues” of course (feel so suicidal, just like Dylan’s Mr. Jones) and in “God” (I don’t believe in Zimmerman). And, even more viciously, in “Serve Yourself”, Lennon’s villainous 1980 parody of “Gotta Serve Somebody”. Sharp and witty, and heartfelt too: on his diary tape of 5 September 1979, his biting “Gotta Serve Somebody … guess he wants to be a waiter now” can be heard – a sneer he unfortunately does not incorporate in his musical answer song.

To McCartney the relationship with Dylan is less sensitive. His winks and reverences are far from conflict-seeking. “Rocky Raccoon” from 1968 (White Album) is perhaps the most sympathetic example. McCartney writes the song in India, according to legend on the roof of the ashram, “with some help” from Lennon and Donovan.

With John Wesley Harding, Dylan has recently put the axe to the psychedelic hippie trend and McCartney conceives the song as a narrative cowboy ballad à la “The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest”. A parody or a copy the song is by no means; it is above all a McCartney song – expertly arranged, descending bass riff, catchy chorus, meandering melody lines.

The Dylan winks are subtle and almost exclusively lyrical. Especially in the irresistible take 8 (on Anthology 3, 1996), in which Rocky is not from Dakota, but:

Rocky Raccoon, he was a fool unto himself

And he would not swallow his foolish pride

Mind you, coming from a little town in Minnesota

It was not the kind of thing that a young guy did

When a fella went and stole his chick away from him

On reflection Macca probably thinks this little town in Minnesota may be a bit overstating, so for the final version he changes it again, this time nodding at the Doris Day song from Calamity Jane (1953): “The Black Hills Of Dakota”. In addition, in this version, Rocky, like Frankie Lee, suffers from foolish pride, the worst of the Seven Deadly Sins. Literally the same words, so Sir Paul scraps those too.

The other references are less flashy, so they may stay. The opponents of Rocky are called Dan and Lil, from which without much literary acumen Dylan can be distilled, Rocky picks up the Bible (twice), just like Dylan does for John Wesley Harding, and with some creative reading into it, there are more subtle hints – the ambiguous, Dylanesque open end, in particular.

Musically, the – tasteful – harmonica stands out. Lennon, presumably, and it is the last time he plays harmonica on a Beatles record.

Parody, homage, ping-pong game with The Beatles or whatever: Dylan takes “4th Time Around” very seriously. It is the first song to be recorded in Nashville, at the restart for Blonde On Blonde on February 14, Valentine’s Day, and he tackles it no fewer than twenty times in succession. The twentieth then is the final take (for comparison: the following “Visions Of Johanna” is done in four takes).

The last recording session (without Dylan, on June 16) is also dedicated to “4th Time Around”, but the overdubs (harpsichord and drums) will not be used. By then, producer Bob Johnston probably realizes that he is already there, with the find of contrasting those lovely guitars with the sarcastic lyrics.

The difference with New York is huge. The acoustic guitars of Joe South and Charlie McCoy, which open the very first session in Nashville, have an elegance that degrades the New York sessions to some rumbling in the garage.

Charlie McCoy is one of the most important secret ingredients of Blonde On Blonde anyhow. Dylan knows the gifted multi-instrumentalist thanks to a sly manipulation manoeuvre by producer Bob Johnston, who lures McCoy and his wife to New York in August ’65 with tickets to a Broadway show. Once in New York, Johnson invites him to the studio, where he just so happens to be working on Dylan’s “Desolation Row”. An acoustic guitar is pushed into McCoy’s hands and he plays the Spanish ornaments that will elevate the monument from a five-star song to a hors category work. Dylan is sold and McCoy later understands that he was a pawn in Johnston’s game:

“Bob Johnston said, ‘You know, I was using you as bait. I wanted Dylan to come to Nashville and he didn’t want to.’ So I was bait and it worked.”

(The Independent, June 24, 2015)

Indeed; when Johnston, half a year later, during those arduous, fruitless recording sessions for Blonde On Blonde in New York proposes to move to Nashville, to Charlie McCoy and his Nashville Cats, Dylan has already overcome his prejudices about those hillbillies with all their songs about slut wives cheating, and he happily agrees.

Lyrically, “4th Time Around” is more ‘ordinary’ than most texts on Blonde On Blonde. Just like in “Visions”, the protagonist confesses to messing around with two women here, but the comparison also ends there. This is nearly a real story; a linear, epic text, almost without inscrutable, symbolic imagery. Bitterly bickering, a man leaves a somewhat hysterical female person and returns to a loving, forgiving lady. The dialogue is briefly, just here and there, somewhat surreal, a dark, symbol-charged image sometimes squeezes itself in, but all in all: a beginning and an end.

“That picture of you in your wheelchair,” for example, is an image puzzling the interpreters – but after the reference to Duchamp’s Mona Lisa in “Visions Of Johanna” (the one with the moustache) this seems like just another, meaningless, joke: presumably Dylan has not only seen the moustachioed Mona Lisa but also the picture of Duchamp and his wheelchair.

However, the lyrics are predominantly remarkably transparent. Well, relatively anyway. Decorated with classical poetic figures of speech, even. She threw me out is neatly placed across You took me in, we hear rhyme and alliteration and repetition, and even encounter an old-fashioned enjambment (That leaned up against / / Her Jamaican rum), all of which is contributing to the contrast effect of this song; the sardonic buffoon wraps his scorn in classical poetry and supports it with an elegant, fizzy melody.

The few artists who risk an interpretation usually stay close to the original. The waltz rhythm, the baroque guitar part – apparently it is difficult to improve.

The most famous cover is certainly beautiful; Yo La Tengo is modest, sultry and hypnotic on the I’m Not There soundtrack (2007). The men from Calexico, the Tex-Mex specialists from Arizona, opt for a dragging slide and a melancholic accordion and suddenly give the song a grieving, lost-love dimension.

The young deceased Texan Chris Whitley, the outstanding guitarist who can sneer ghastly with his unique, hoarse voice, produces a cutting-edge version on a live recording from 2003 (On Air, 2008). His studio recording, on Perfect Day (2000) is superb, too (though his “Changing Of The Guards”, with Jeff Lang on 2007’s Dislocation Blues remains his unsurpassed masterpiece).

Almost-the-most-beautiful cover is the contribution to Amnesty International’s birthday project, Chimes Of Freedom (2012) by the Israeli world citizen and Jack-of-all-trades Oren Lavie. Lavie replaces “Norwegian Wood” with “Tomorrow Never Knows” and only preserves the vocal melody, actually – and that works perfectly.

The most remarkable and appealing, however, is the adaptation by The Young Relics, also from Texas, on their eponymous EP from 2009. Jumping, neurotic and contagiously energetic, including a pleasantly surprising, completely unexpected change in rhythm; halfway a full organ brutally descends down, calming the nervous guitar, smothering all the unrest, crushing every last splinter of Norwegian wood.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/199/Fourth-Time-Around

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.