by Jochen Markhorst

Somewhere in the last part of his Black Coffee Blues trilogy, in “Smile, You’re Traveling” (2000), the multifaceted phenomenon Henry Rollins expresses his love for Sinatra, and specifically for his 50s albums:

Somewhere in the last part of his Black Coffee Blues trilogy, in “Smile, You’re Traveling” (2000), the multifaceted phenomenon Henry Rollins expresses his love for Sinatra, and specifically for his 50s albums:

“I like the records he did where he’s all bummed out like In the Wee Small Hours, No One Cares, Where Are You and Only the Lonely. I like Sinatra because all his life he’s been saying fuck all you motherfuckers with the talent to back it up. He kept coming back no matter what was thrown his way. He inspires me big time. He’s like a swan, graceful but mean when confronted.”

Fifteen years later, Elvis Costello writes a very similar declaration of love in his autobiography, in Unfaithful Music & Disappearing Ink:

“I spent nights deep in The Wee Small Hours of the Morning, No One Cares, and Only the Lonely, that incredible run of intense ballad albums that Sinatra had cut for Capitol with Nelson Riddle.”

Dylan confesses that same love a little more indirectly, in Chronicles, when he unpacks a lot to describe his awe for the song “Ebb Tide”: “The lyrics were so mystifying and stupendous. When Frank sang that song, I could hear everything in his voice — death, God and the universe, everything.”

https://youtu.be/_b6JNRvOat4

“Ebb Tide” is on Side 2 of Frank Sinatra Sings For Only The Lonely (1958) and traces of that album can be found throughout Dylan’s entire oeuvre. In songs like “Forgetful Heart”, “Dignity” and “Wallflower” resonate word choice and song structure, Only The Lonely songs like “One For My Baby (And One More For The Road)” and “Good-Bye” are paraphrased in the Basement, in “Sign Language”, in “Scarlet Town” and in “Don’t Think Twice”, and with some cut and paste work, the classic “Blues In The Night” can be reconstructed in its entirety from Dylan’s Collected Works.

“Blues In The Night” should be somewhere on the first pages of The Great American Songbook. Even composer Harold Arlen, usually a modest man who can’t be caught on selfcongratulatory behaviour, gets excited again when his biographer Edward Jablonski asks about this song: “I knew in my guts that this was strong, strong, strong!” (Rhythm, Rainbow And Blues, 1996 ). He even takes, very unusually, credit for some of the lyrics by Johnny Mercer:

“It sounded marvelous once I got to the second stanza but that first twelve was weak tea. On the third or fourth page of his work sheets I saw some lines—one of them was “My momma done tol’ me, when I was in knee pants.” I said, “Why don’t you try that?” It was one of the very few times I’ve ever suggested anything like that to John.”

(Source: Alec Wilder’s American Popular Song, 1972)

True; it is an exceptional song. Written for the film Hot Nocturne in 1941, but after the success of the song the film title is changed to Blues In The Night. A year later, the song does not win the Academy Award for Best Song. One of the many injustices in the history of the Oscar awards, but it does get a coda. Winner Jerome Kern (“The Last Time I Saw Paris”), who is actually known as a quite competitive, somewhat arrogant song composer with a strong ego, is ashamed. To make up, he gives Arlen a remarkable, personal gift (the walking stick of Jacques Offenbach) and he ensures that the rules of the game are changed: from 1943, an Oscar-nominated song must actually have been written for the film. Kern’s winning “The Last Time I Saw Paris” was an old song that, more or less coincidentally, was inserted at the last minute in the film Lady Be Good. Not an Oscar winner, as Kern himself thought at the time, so he wasn’t even present at the award ceremony.

Dylan is a fan of lyricist Johnny Mercer, and especially of this song, although in Chronicles he still seems to think it’s all Harold Arlen:

“Arlen had written “The Man That Got Away” and the cosmic “Somewhere Over the Rainbow,” another song by Judy Garland. He had written a lot of other popular songs, too — the powerful “Blues in the Night,” “Stormy Weather,” “Come Rain or Come Shine,” “Get Happy.” In Harold’s songs, I could hear rural blues and folk music. There was an emotional kinship there.”

Of course; Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Hank Snow… they are all deeper under his skin, “but I could never escape from the bittersweet, lonely, intense world of Harold Arlen.”

Copywriter Johnny Mercer does not get explicit credits from the bard, but indirectly more than once. From this song, from “Blues In The Night”, the Dylan fan recognizes

Now the rain’s a-fallin’

Hear the train a-callin

… of which echoes descend in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and in “Dusty Old Fairgrounds”, the fourth verse opens with

From Natchez to Mobile

From Memphis to St. Joe

… that should sound familiar too, and the chorus,

The evenin’ breeze’ll start the trees to cryin’

And the moon’ll hide it’s light

When you get the blues in the night

Take my word, the mockingbird’ll sing the saddest kind of song

He knows things are wrong, and he’s right

… reveals where Dylan borrowed that atypical combination of moon and mockingbird from “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” (and that last line comes very close to “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome”, first verse – when something’s not right, it’s wrong).

Together with “Down Along The Cove”, “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is the odd song out on John Wesley Harding. After ten songs with mysterious, biblical, parable-like lyrics such as “All Along The Watchtower”, “Drifter’s Escape” and “Dear Landlord”, the album closes with two genuine country songs, both love songs with simple language, simple lyrics without extravagancies like barefoot servants, fairest damsels or obscure saints wrapped in solid gold, and they are the only songs on the record in which a steel guitar plays along (Pete Drake).

In retrospects and review articles, the songs are often referred to as “transition songs,” as a transition to, or some sort of strategic, announcement of the country on the next album, on Nashville Skyline. Dylan himself does not agree with that, at least: with the assumption that he would have a preconceived strategy, that at the time of John Wesley Harding he would already have had ideas about the next album. But, obviously, it is undenialble that both songs would fit on Nashville Skyline without any problems.

The last two songs are also recorded last, written last and, unlike the other ten songs, written on the spot, where according to Dylan music and lyrics came simultaneously – for the other songs he had written the lyrics well before.

Thus the Spirit of Nashville, country capital of the world, finally gets hold of Dylan after all. Ironic, because Dylan himself had just relieved the city of that stamp by recording Blonde On Blonde in Nashville. The previously prevailing provincialism and the one-sidedness of the music scene before Blonde On Blonde the reminiscing autobiographer expresses, rather crassly, in Chronicles:

“The town was like being in a soap bubble. They nearly ran Al Kooper, Robbie Robertson and me out of town for having long hair. All the songs coming out of the studios then were about slut wives cheating on their husbands or vice versa.”

… and “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is not that far behind. Admittedly, the text is vague enough to be able to deny adultery is committed here. With some creativity one could even say that the sung Baby is literally a baby, that Dylan is writing a lullaby for the one and a half year old Jesse Dylan. But Ockham’s razor points to the most obvious interpretation: an I-person who sings “I’ll be your sweetheart tonight” is not the lawful life partner of the person to whom the song is sung – but probably a slut wife cheating on her husband or vice versa.

Totally unimportant, of course. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is a beautiful song, with the shine of an indestructible evergreen, which is almost immediately recognized by the front fighters of both the country and pop world.

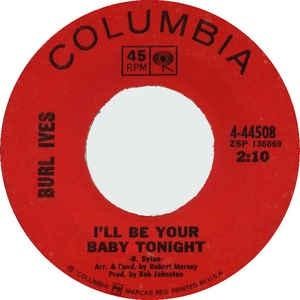

The superpower Burl Ives records his version as early as 1968, a few months after the release of John Wesley Harding, for his album The Times They Are A-Changin’, on which he covers no fewer than four Dylan songs (also “One Too Many Mornings” and “Don’t Think Twice It’s All Right” – Burl writes it without a comma).

The covers are rather controversial. The producer is Dylan expert Bob Johnston, who recorded the original a few months before. The album is recorded in the same studio in Nashville and though the sleeve does not mention musicians, it is likely that the Nashville Cats, Charlie McCoy and Kenny Buttrey are on duty again. But it is arranged quite horribly, with tormenting violins, corny female choirs and a theatrically talk-singing Ives.

The covers are rather controversial. The producer is Dylan expert Bob Johnston, who recorded the original a few months before. The album is recorded in the same studio in Nashville and though the sleeve does not mention musicians, it is likely that the Nashville Cats, Charlie McCoy and Kenny Buttrey are on duty again. But it is arranged quite horribly, with tormenting violins, corny female choirs and a theatrically talk-singing Ives.

“I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is the exception. It’s not too bad – Burl just sings, the violins hold back – it is rightly chosen as a single and it is both in America and in Australia a modest hit (numbers 35 and 28 respectively).

Equally eager are Emmylou Harris, Ray Stevens, George Baker, Anne Murray and many more artists; before 1970, within two years, half the premier division already has the song on the repertoire.

The popularity does not decrease after 1970. “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is undoubtedly high on a (non-existent) list of Most Covered Dylan Songs, and is often chosen as a single. The Hollies, Judy Rodman, Bobby Darin, John Walker (of the Walker Bothers), Blossom Toes … that list is endless too.

The biggest success is the one-off project Robert Palmer & UB40, which achieves a major hit in 1990 with a tolerable, cute reggae arrangement of the song.

Dylan’s heart probably skipped a beat when Hank Williams Jr., the son of his great hero, covered the song. Only for sentimental reasons, however – Hank’s cover is intolerably smooth.

Unreal, and much more fun, is the former Deep Purple singer Ian Gillan, turning it into a cheerful, cajun-like sing-along (on Gillan’s Inn, 2006).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=C27YpoExSzY

But real beauty, real moving power cannot be found that often. For the time being this is limited to two almost perfect masterpieces, both of which also manage to extract something from the original that Dylan himself only partly achieves.

The first, and actually the best, is Norah Jones, the exceptionally talented daughter of Ravi Shankar, who also sings such a crushing “Heart Of Mine”. Her “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” is sultry, a bit ordinary and sexy – exactly what the song calls for. On Stay With Me, 2003.

Well alright, of equal merit is the rendition of Curtis Stigers, not coincidentally also from the jazz corner, with a cool swinging, lazy jazz performance – even better live than the studio version (Real Emotion, 2007).

Apparently Dylan, despite the unmistakable country overtones, injected subcutaneously Wee Small Hours. A Blues In The Night is hidden in it, which only the real jazz talents are able to uncover.

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.