by Jochen Markhorst

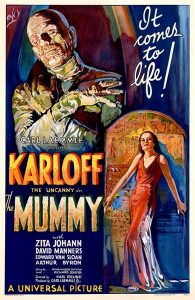

The western fascination for the exotic mysticism of ancient Egypt is even older than the introduction of Egyptology in the nineteenth century. Already in Mozart’s Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute, 1791), the opera full of freemason mystique, the sage Sarastro invokes Isis und Osiris, standing in a setting of pyramids and palm branches. The appeal culminates in the following decades; the time of the pharaohs inspires thousands of operas, literary works, paintings and later also films (Cleopatra from 1917, for example, and the entire series of Mummy horror films starting in 1932).

The western fascination for the exotic mysticism of ancient Egypt is even older than the introduction of Egyptology in the nineteenth century. Already in Mozart’s Zauberflöte (The Magic Flute, 1791), the opera full of freemason mystique, the sage Sarastro invokes Isis und Osiris, standing in a setting of pyramids and palm branches. The appeal culminates in the following decades; the time of the pharaohs inspires thousands of operas, literary works, paintings and later also films (Cleopatra from 1917, for example, and the entire series of Mummy horror films starting in 1932).

After the Second World War, the theme fades a bit, but it never disappears. Tintin and The Cigars Of The Pharaoh is a bestseller in 1955, Asterix and Cleopatra in 1965, Indiana Jones travels with Ra’s Staff to Cairo (Raiders Of The Lost Ark, 1981), The Bangles score their world hit in 1986 (“Walk Like An Egyptian”). And even today, the perfume industry tempts customers with the scent “Egyptian Godess” (Auric Blends, $9.98 on amazon.com).

So the Isis and the pyramids from Dylan’s song do not stand on their own, but are part of an age-old tradition of Egyptian references in Western culture. And much more than that it is not, according to Jacques Levy, the co-author. In one of his last interviews, for Prism Films in May 2004, he tells quite extensively about his collaboration with Dylan.

“We didn’t get into “What do you mean by this, what’s all this” kind of stuff. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve been asked the significance of the fifth day of May. And I just fend it off. I don’t know the significance. And I don’t care. I tell people: make up your own significance. (…)

Exotic is a good word (…) The sense of a foreigness. It was exotic, but there was also some aspects of autobiography in the song. Whether mine or Bob’s. (…)

I was very interested in Western stuff, in cowboy stuff. Stuff I’d written with McGuinn all had that kind of Western flair. And a couple of songs I wrote with Bob had that too. Take a song like “Isis”. “Isis” is this cowboy story, but there’s very little that’s Western about it. The music isn’t Western and the images aren’t Western. But it feels more like a cowboy story taking place through some other kind of lens.”

Just like those Egyptian elements, those autobiographical elements are at most insignificant flavour enhancers. Isis is called a mystical child – in the complete Dylan catalog that adjective appears only in one other song: in “Sara”, on this same album Desire, the same Sara who wears a magical Egyptian ring in “She Belongs To Me”. Apparently the poet thinks of his future ex-wife as an ancient Egyptian beauty. The link between the names Sara and Isis is soon made – it takes place along the same lines on which Kafka calls his protagonist “Samsa”, Klaus Mann renames his collaborating brother-in-law Gustav Gründgen to “Hendrik Höfgen” (in Mephisto, 1936) and Neal Cassady changes to Dean Moriarty (On The Road, Jack Kerouac).

In the enlightening SongTalk interview with Paul Zollo, Dylan too confirms that limited depth:

“With this Isis thing, it was Isis…. you know, the name sort of rang a bell but not in any kind of vigorous way. So, therefore, it was name-that-tune time. It was anything. The name was familiar. Most people would think they knew it from somewhere. But it seemed like just about any way it wanted to go would have been okay, just as long as it didn’t get too close. (laughs)”

Not too close to himself, Dylan explains (laughing still), when asked.

A nice little story, in short. And we don’t mean anything else by that, Dylan claims a few years earlier too, to the question of a listener when the singer patiently answers questions, an hour in a radio studio in Hollywood. “It’s kind of like a journey, you know, like sort of a journey type trip. (…) I don’t really know too much in depth what it would mean.”

Like sort of a journey type trip is a very scanty summary of the fateful odyssey that the main character from “Isis” undertakes, but Dylan’s point is clear: the sparkle of the song is not so much in the narrative quality, and certainly not in hidden meanings, but in the visual power, the unexpected turns and the beauty of the words. The protagonist undertakes a long journey full of hardships and eventually returns to his legal wife – a real odyssey, something like Odysseus did.

It is not very clear where Levy sees a cowboy story. The main characters travel on horseback, that’s about it. And the word canyon is spoken, but then again; this canyon is icy and snowy, not exactly the kind of canyon one would immediately associate with the Wild West. In fact, the ballad is teeming with decor pieces and props that push the imagination half a world the other way. The main characters meet at the launderette, travel to the cold North and find an empty tomb in an icy pyramid. The backdrop of the homecoming is a grassy meadow near a dry creek, at sunset.

The listener does not see Once Upon A Time In The West, but rather apocalyptic landscapes from a movie like Mad Max or the Bible book Ezekiel, or fantasy worlds like in The Lord Of The Rings. In any case “exotic”, that part of Levy’s analysis is traceable.

The dialogues are no less enigmatic and through and through Dylanesque. Conversations brushing past each other, answers that don’t answer, dialogues that only seemingly make sense.

“Where are we going?”

“We’ll be back by the fourth.”

“That’s the best news that I’ve ever heard!”

He comes back from the Cold North, has just put the body of his companion in an empty tomb in an icy pyramid. But when asked, that was “no place special”.

Tone and the confusing content of the dialogues are comparable to Kafka’s parables, but also from Dylan’s more surreal press conferences and interviews. And Dylan’s life partners undoubtedly recognize it too. “You who are so good with words and at keeping things vague,” as Joan Baez would put it in “Diamond & Rust”. Infuriating when trying to decide on a new ceiling lamp together at the Ikea, but in a song text like “Isis” these kinds of dialogues get an irresistible, deeply poetic shine.

Just as irresistible is the music, or rather: Dylan’s recital. The musical accompaniment is simplistic and effective, really no more than a rolling, falling ostinato (Ⅰ–ⅤⅠⅠ♭–Ⅳ–Ⅰ). Hypnotising enough, but the interpretation elevates the song to a Dylan classic. And not so much because of the combination of the stubborn, mesmerizing piano hammering and the elegant, enticing violin and the driven harmonica; it is mainly Dylan’s vocal performance. The bard sings masterfully meandering around those piano chords, powerful and confident, stretching vowels so that the words merge into one – as if he is playing a saxophone solo. Take a verse like the opening line of verse three, “A man in the corner approached me for a match”; a serpentine of dancing, waltzing sounds, the meaning of which, indeed, is actually no longer important.

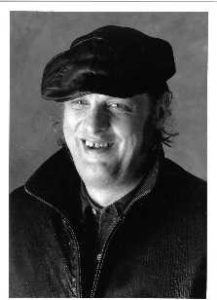

Underexposed is the remarkable supporting role of the drums. Most hits from the exceptional talent Howie Wyeth (also a fairly skilled ragtime and jazz pianist) are just milliseconds outside the beat, granting the recording this fascinating, driving dynamic.

Underexposed is the remarkable supporting role of the drums. Most hits from the exceptional talent Howie Wyeth (also a fairly skilled ragtime and jazz pianist) are just milliseconds outside the beat, granting the recording this fascinating, driving dynamic.

Dylan is impressed too. “Your drummer sounds great,” he tells bass player Rob Stoner, who brought his drum buddy to the studio. He is then subsequently invited to the Rolling Thunder Revue. Howard Wyeth has more successful sessions to his name, with Don McLean for example, and with Roger McGuinn, on his most beautiful album, Cardiff Rose. On the continent he is known from the smashing piano solo and the dry, tight drums on the hit “Red Hot” by Robert Gordon and Link Wray (1977), although he is playing on the bass in the videoclip (and bassist Rob Stoner is at the drums).

But at his premature death in 1996 (51 years old), his work on Dylan’s Desire still ranks as his moment of glory.

But at his premature death in 1996 (51 years old), his work on Dylan’s Desire still ranks as his moment of glory.

The fellow musicians are in awe. Few colleagues risk a cover – Dylan’s studio version and the live versions are fairly unassailable and presumably too daunting a challenge. The massive, white blues giant Popa Chubby has had the song on his repertoire for a few years and comes close to what Jimi Hendrix would have made of it.

The fellow musicians are in awe. Few colleagues risk a cover – Dylan’s studio version and the live versions are fairly unassailable and presumably too daunting a challenge. The massive, white blues giant Popa Chubby has had the song on his repertoire for a few years and comes close to what Jimi Hendrix would have made of it.

The 1996 recording is one of the most beautiful. Even better than the only more or less well-known cover of “Isis”, the one by The White Stripes.

The ultimate cover does and will not exist. Dylan surely would have been delighted by Umm Kulthum, Egypt’s national icon, “The Planet Of The East”, “Egypt’s Fourth Pyramid”, the singer he explicitly honours in the Playboy interview with Ron Rosenbaum, 1977:

“She does mostly love and prayer-type songs, with violin and-drum accompaniment. Her father chanted those prayers and I guess she was so good when she tried singing behind his back that he allowed her to sing professionally, and she’s dead now but not forgotten. She’s great. She really is. Really great.”

It is quite conceivable that Dylan copied the Eastern garlands in “Isis”, “One More Cup Of Coffee” and “Mozambique” from her.

But alas, no Egyptian “Isis”. Mrs. Kulthum dies on February 3, 1975, a year before Desire is in stores. We can only dream away on the fantasy of how Dylan’s love and prayer-type song would have sounded with Arabic violins and drums – and with Umm Kulthum.

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

I hadn’t heard “ISIS” in years so I pulled it up to listen to and eventually ended up here. Our band, Th’ Mighty Argentina Turner Band, opened for Bob on Maui 4/22/92. After our set we were backstage when he came up with George Harrison who I patted on the shoulder as I said, “ Go get ‘em Bob!” What a thrill it was!

I had earlier met his mom at a deli/bookstore in West St. Paul in 1988. I overheard an older woman telling this younger woman that she was Bob Dylan’s mom. Given that we were in Minnesota I thought it was possible, so I went up to the woman at the register and asked if she knew if the woman was Bob Dylan’s mother. The cashier said, “Oh yes, she comes in here all the time.”

So I waited until the two finished talking, introduced myself and asked, “Mrs. Zimmerman, you do know don’t you the effect your son has had on our culture?” to which she replied, “Oh honey, I divorced that man a long time ago,” and told me her name. She then went on to tell me that she had put poetry Bob wrote as a young child into a safe deposit box for his children. She was a very nice person.

Those are my two Bob Dylan stories. Thank you Bob for the spirit and the music- Bubba

Thanks for all that background information, a good read!

One way of making sense of this song: Isis could represent a soul aspect that the narrator is touched by, but he is not mature enough yet to maintain a lasting connection. So he has to embark on his adventure to prepare himself for “the next time we wed”. His companion might represent character traits he needs to overcome. His death may relate to “mystical death”, overcoming one’s ego. This happens at the pyramids, an ancient place of initiation …

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/314/Isis

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.