by Jochen Markhorst

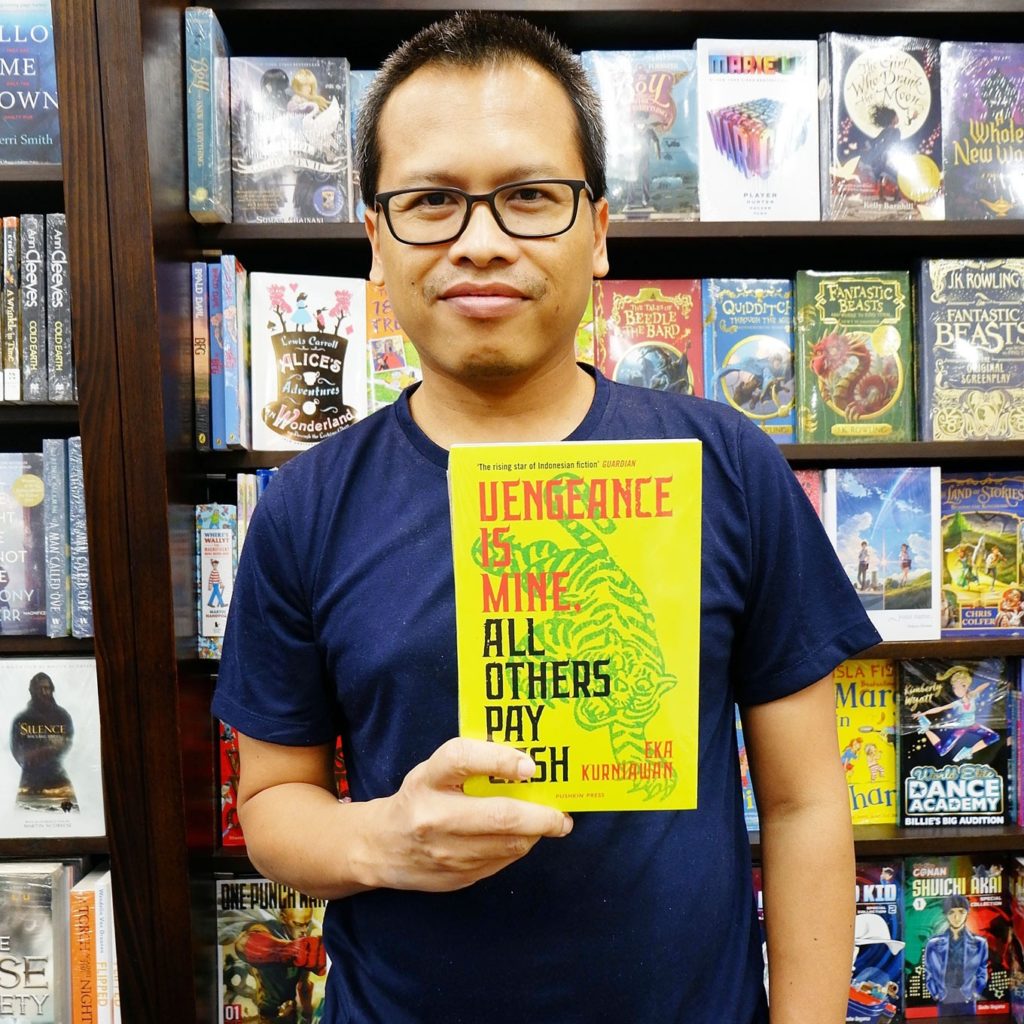

Indonesian writer Eka Kurniawan writes beautiful books and will one day win the Nobel Prize for his magical-realistic, sociocritical oeuvre, but he cannot write songs. “It’s the hardest thing there is. You have so few words at your disposal,” he analyzes, with regret, in the Dutch Volkskrant interview, 26 January 2019. “I tried, but I can’t. With me, a small story quickly expands. (…) Songwriters make a reverse movement: they can turn a big story into something very small.”

He says so when expressing his admiration for “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”, that he got to know in the Guns ‘n’ Roses version. And by extension, he declares to be a fan of the Indonesian Bob Dylan, Iwan Fals: “I love how he tells little stories in his songs.”

Author Rudy Wurlitzer, the screenwriter of Pat Garrett & Billy The Kid, shares Kurniawan’s admiration, but especially admires the circumstances under which and the speed with which the bard manages to fabricate that song:

“Bob wrote the film score in Mexico City,” Wurlitzer says. “But before that, one night when we were returning to Durango from Mexico City – I forget why we were there – he said he wanted to write something for Slim Pickens’ death scene, which was due to be shot the next day. He scrawled something on the airplane and showed it to me line by line and when we got off the plane, there it was, Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door.”

Wurlitzer also tells how Dylan prepares for the film, the zeal with which he plunges himself into the project and he claims that Dylan gets the role in that film through him:

“When Dylan heard that a Billy the Kid film was in the works, he came to see me at my place on the Lower East Side wanting to know if there was any way he could be a part of it. He said he was Billy the Kid in a past life. After I wrote a part for him, we flew to Durango so that he could meet Sam. We walked up to his house after dinner where Sam was drinking alone in his bedroom and staring at himself in a full-length mirror. He turned to Dylan and said, “I’m a big Roger Miller fan myself. Not much use for your stuff.”

(interview in Arthur Magazine, May 2008)

But Bloody Sam Peckinpah’s disinterest turns into adoration after he gives Dylan the chance to sing “Billy”, as James Coburn knows. Protagonist Coburn (Pat Garrett) does not mention that rejecting Roger Miller remark, but knows quite well that Peckinpah had no idea who Dylan was (“Sam didn’t know who the fuck Dylan was”). However, he also remembers that the director was converted already after one listening session:

“But when he heard Dylan sing, Sam was the first to admit he was taken with Dylan’s singing. He heard Dylan’s Ballad of Billy the Kid and immediately had it put on tape so that he could have it with him to play.”

(interview with Garner Simmons in: Peckinpah: A Portrait in Montage, 2004)

“Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” is of course an unassailable monument. The song is one of the most covered Dylan songs, and probably one of the most covered songs of all. The film site imdb.com counts 78 films and television series that use the song for the soundtrack, and anyone who has ever held a guitar has played this song.

The popularity, however, is not due to the quality that writer Kurniawan so admires, not to “a big story” that is cast into “something very small”. Knockin’ has very few words indeed (about 45), but those few words don’t tell a story – this is lyricism, the articulation of a feeling.

On that front, this short text does a great job, and that, in particular, must have touched screenwriter Wurlitzer.

Rudy Wurlitzer displays his talent in writing novels and film scripts, and has proven himself in both fields. His experimental, psychedelic debut novel Nog (1968) immediately attracts attention and earns him his first film assignment: rewriting the script for the cult classic Two-Lane Blacktop (1971), the only film in which James Taylor can be seen as an actor. Kris Billy The Kid Kristofferson sings his own “Me And Bobby McGee” for the soundtrack and Harry Dean Stanton, who somehow runs through Dylan’s life as a continuous thread, plays a supporting role.

Substantive references to the film can be found here and there, in Dylan’s songs (Tail of the dragon in “Señor”, for example), but especially Wurlitzer’s style and theme seems to penetrate into “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”: expressing with as few words as possible the paradox of fearing and welcoming death at the same time.

Wurlitzer himself thanks his teacher Robert Graves (the writer of I, Claudius) for his skills to “write short sentences” and perhaps best demonstrates this particular talent in the underrated and unjustly forgotten masterpiece Homo Faber (1991, Volker Schlöndorff), the film adaptation of one of Max Frisch’s three Great Novels.

The leading role in that film is played by that other greatness in the field of condensed, meaningful film scripts, Sam Shepard (Paris, Texas being the highlight), but as far as is known, Shepard does not interfere with this scenario. Walter “Homo” Faber is a twentieth-century Oidipus, a poor communicator, who firmly believes in technology, control and rationality – and for that, Fate punishes him with improbable, cruel “coincidences”. Wurlitzer’s script is sparse, brooding and overflowing under the surface – demonstrating Kurniawan’s ideal; telling a big story with few words.

Thematically, Wurlitzer also aims at what Dylan manages to achieve in those few words of “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door”: reconciling extremes, as Dylan does with the extremes fear of death and resignation.

Deputy Cullen Baker (Slim Pickens) has been fatally hit and stumbles to the bank of the river, where he collapses, leaning on a large rock. Upset, his tough wife (Katy Jurado) sees it happening. She rushes towards him, but does not dare, cannot bring herself to take the last steps and sinks down, broken, three meters away from her beloved husband and watches silently crying as he dies, in his eyes a mixture of regret and resignation, looking out over the peaceful, slow flowing river in the evening light.

And over it all, “Knockin’ On Heaven’s Door” swells up, the lyrics of which not only convey this specific death scene, but the entire film as a matter of fact: that cold black cloud is comin’ down, feels like I’m knockin’ on Heaven’s door.

The chosen imagery is not new and illustrates the grand mastery of the cherry-picking thief of thoughts Dylan. The text is actually an amalgam of “Fixin’ To Die”, Bukka White’s classic that Dylan sings on his first album, and “Trying To Get To Heaven” by Reverend Gary Davis, and especially Al Koopers version with the chorus “Tryin’ to get to heaven in due time / Before the heaven doors close” (“Wake Me Shake Me”, The Blues Project, 1966)… which will descend even more literally in “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven” (1997, Time Out Of Mind), of course.

Part of the popularity among fellow musicians is due to the simplicity of the music. Only three chords, G-D-C, well alright: four (the C is interspersed with twin sister Am7), a chord scheme that every beginning guitarist has in his fingers after an hour. Although, according to George Harrison, it is not that easy, as he notes in an interview with Paul Cashmere, 1993:

PC: Have you heard Guns ‘n’ Roses “Knocking on Heaven’s Door”?

GH: Yeah, didn’t even get the chords right, did they?

PC: So I take it you’re not a big fan of that one, then?

GH: There’s only three chords in it, but they managed to get one of them wrong. (laughs)

A bit vicious, but funny still. Meanwhile, the cover of Guns ‘n’ Roses is the most successful version of the song (Top 10 in fourteen countries, in three of them at number 1) and whatever one may think of Axl Rose’s vocal acrobatics: he can sing, with its incredible range of five octaves and some. The talents of guitarist Slash are generally recognized as well, even by Dylan (Slash is invited to the sessions of under the red sky). And oh well, cheating with the chord scheme does suit the rebellious image of the band.

For the lyrics, Axl Rose does respectfully stick to the published lyrics, although that happens to be the part of the song which is not carved in stone. Dylan sings dozens of variations. An outtake of the original sessions in Burbank, February ’73, has an extra couplet, the long black cloud is a long black train, and the Before The Flood version of 1974 even has an extra, third couplet:

Mama wipe the blood from my face

I’m sick and tired of the war

Got a lone black feelin’, and it’s hard to trace

Feel like I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door

During the Rolling Thunder Revue (’75 -’76) the lyrics differ almost every evening. Other than “blood from my face” Mama also takes “bells out of my ears”, “tears out of my eyes”, “my barge down the sea” (Deputy Baker builds his own sloop and dreams of sailing away), but the most solemn, old-fashioned, antiquish version is for Roger McGuinn to sing, Waterbury, November ’75:

Mama I can hear that thunder roar

Echoin’ down from God’s distant shore

I can hear it callin’ for my soul

Feel I’m knockin’ on heaven’s door

Those who are eager to find autobiographical traces in Dylan’s songs can indulge in the 1981 versions, when the bard sings repeatedly: Two brown eyes are looking at me. On the other hand: “Mama”, Mrs. Cullen Baker (Katy Jurado), also has big, beautiful, brown eyes. Just ask John Wayne, Elvis, Marlon Brando, Ernest Borgnine, Tyrone Power, all those men who were so fortunate as to look into those eyes up close, and generally succumbed:

“Her enigmatic eyes, black as hell, pointing at you like fiery arrows”

(from: Darwin Porter, Brando Unzipped, 2006)

… Marlon Brando, for one, is feeling as if he is knocking on a gate to heaven.

The covers are uncountable. A site like secondhandsongs.com gives up after 139 versions, allmusic.com yields 633 hits (though with quite a few double counts), Björner comes to 165 and Wikipedia doesn’t even try, but limits itself to mentioning the most famous ones.

Warren Zevon’s subdued adaptation, recorded just before his death, is heartbreaking. Guns ‘n’ Roses and Clapton are the best known, Randy Crawford, Kevin Coyne and Roger Waters are special, but the Dunblane Tribute, the rewritten version that is recorded for charity with Dylan’s permission, really stands out.

Following the horrific shooting of school children in the Scottish village of Dunblane, in which a 43-year-old man kills fifteen children between the ages of five and six plus a teacher, musician Ted Christopher rewrites the lyrics. Mark Knopfler helps free of charge and in the Abbey Road studios, with a choir of brothers and sisters of the victims, the single is recorded on December 9, 1996. It immediately climbs to first place in the English charts.

Psalm 23 is incorporated in it (The Lord is my shepherd), the second verse has been rewritten and a third verse has been added:

Lord these guns have caused too much pain

This town will never be the same

So for the bairns of Dunblane

We ask please never again

Lord put all these guns in the ground

We just can’t shoot them anymore

It’s time that we spread some love around

Before we’re knockin’ on heaven’s door

Nobody knows what possessed the murderous coward, who commits suicide on the spot. Heaven’s Door remained closed to him, in any case.

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/345/Knockin-On-Heavens-Door

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.