Changing Of The Guards (1978) by Jochen Markhorst

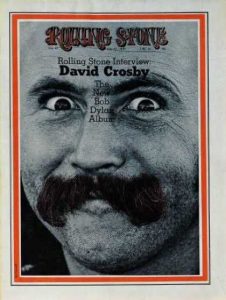

Dylan is now only a big name from the past, the bitterly disappointed Greil Marcus argues, in his famous What-is-this-shit review of Self Portrait in the Rolling Stone of July 23, 1970. Unless … “unless he returns to the marketplace, with a sense of vocation and the ambition to keep up with his own gifts.”

Dylan is now only a big name from the past, the bitterly disappointed Greil Marcus argues, in his famous What-is-this-shit review of Self Portrait in the Rolling Stone of July 23, 1970. Unless … “unless he returns to the marketplace, with a sense of vocation and the ambition to keep up with his own gifts.”

Eight years later, in the poetic explosion with which he opens the Street Legal album, in “Changing Of The Guards”, the poet responds: “I stepped forth from the shadows, to the marketplace.”

In a similar, reflective interpretation, the opening lines, sixteen years, sixteen banners united over the field, are a reference to the sixteen years Dylan has been active as a recording artist and to the sixteen studio records he has delivered so far.

Nice find, but not very likely. Such an all too personal retrospective of his own career would be very, very atypical, far too vain and petty for a poet who often, and credibly, says: je est un autre. The private worries the poet Dylan lets trickle down into his work always have a universal, ego-transcending value; the passing of time, the loss of a love, the human condition – something as egomanic as my sixteen years in the market place fits in poorly.

The baroque exuberance of the text fascinates and invites to take a stand, that much a trip through the fields makes clear. In addition, many clarifiers remain stuck in the – not always admiring meant – conclusion that the lyrics are so ambiguous. That is euphemistic; in the vast majority of analyses, the reader is taken along a few more and less far-fetched associations, to discover at the end that the analyst is unable to produce one single interpretation, let alone more interpretations. And those few Dylanologists who bravely attempt to capture “Changing Of The Guards” in one conclusive interpretation, go down struggling.

David Weir, who fills his otherwise enjoyable blog Bob Dylan Song Analysis with well-written, worth-reading interpretations, knows that the song is about the life of Christ, “from before his birth to after the resurrection”. For that interpretation, contortionist Weir squeezes and bends himself in some quite impossible twists and turns. The enigmatic line he’s pulling her down, and she’s clutching onto his long golden locks, for example, actually means: He, the risen Jesus, pulls God (“she”) down to earth so that He and God can unite to a whole. And if, for the sake of convenience, we’d be so good to read the sun is breaking as the son is breaking, then that verse does tell of the resurrection of Jesus.

Mr. Weir is not the only one who seizes Dylan’s upcoming conversion to Christianity as the key to text explanation, but he is the only one who tries to squeeze almost every image from the text, with laudable stubbornness and creativity, into that mold. Without success in the end; the Saviour’s biography as a key to the work is not at all convincing. The same goes for cherry-picking analysts such as Prof. R. Clifton Spargo, who finds the song a “stunning rewriting of the Samson story”, triggered by the mentioning of a shaven head (of a woman, unfortunately) and broken chains. Or Clinton Heylin, who suspects a “Babylonian narrative of lust and betrayal”, whatever that may be, but ultimately opts for the End Times.

The Apocalypse is seen by more readers. The most creative cryptoanalyst is a blog reader who points out to David Weir that the number 16 in sixteen years and sixteen banners was probably not chosen at random. Revelation 16:16 reads “And he gathered them together into a place called in the Hebrew tongue Armageddon” – the Bible verse that reveals the location of the Last Battle, also the place where the I-person on Side 2, in Señor, fears to go.

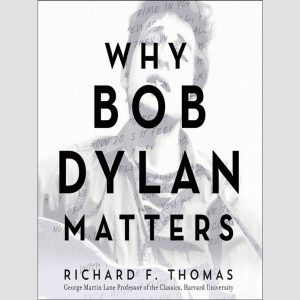

Harvard professor Richard F. Thomas produces the most fascinating commentary on “Changing Of The Guards”. The Professor of Classical Languages is becoming quite a name in Dylan circles. Not only due to his resounding, erudite article from 2007, The Streets Of Rome: The Classical Dylan, but also because he alternates his lectures at Harvard on Homer, Virgil and Ovid with a lecture block on Dylan, to the dismay of some of his academic colleagues. Thomas distilled the brilliant work Why Dylan Matters (2017) from that famous lecture block and therein he devotes an entire section to The Guards.

Harvard professor Richard F. Thomas produces the most fascinating commentary on “Changing Of The Guards”. The Professor of Classical Languages is becoming quite a name in Dylan circles. Not only due to his resounding, erudite article from 2007, The Streets Of Rome: The Classical Dylan, but also because he alternates his lectures at Harvard on Homer, Virgil and Ovid with a lecture block on Dylan, to the dismay of some of his academic colleagues. Thomas distilled the brilliant work Why Dylan Matters (2017) from that famous lecture block and therein he devotes an entire section to The Guards.

Thomas is, obviously, taken with Dylan’s words from the interview with Jonathan Cott from 1978. “Changing Of The Guards is a thousand years old (…), might be a song that might have been there for thousands of years, sailing around in the mist and one day I just tuned into it.”

Dylan’s statements in this very conversation are often quoted and that is understandable. The master seldom elaborates on his songs and here he vents some pleasantly misty, very Dylanesque hints. “We’re all dreaming, and these songs [from Street Legal] come close to getting inside that dream. It’s all a dream anyway,” and “It means something different everytime I sing it.”

Seemingly very revealing and mysterious at the same time, but what both Thomas and all those others prefer to ignore: the words are almost literally put into Dylan’s mouth by the interviewer.

JC: The lines, “She’s smelling sweet like the meadows where she was born/On Midsummer’s eve, near the tower,” are so quiet and pure.

BD: Oh, yeah?

JC: Those lines seem to go back a thousand years into the past.

BD: They do. Changing Of The Guards is a thousand years old.

Despite that, despite the few serious outpourings by Dylan himself, Prof. Thomas, the expert in ancient literature, goes looking. He acknowledges that the song, with all these peculiar images, situations and characters, escapes a comprehensive interpretation. But he does think that the lyrics owe much to both the world of Rome and the Biblical world, given the clear references. He is then triggered by the image on the page next to “Changing Of The Guards” in The Lyrics 1961-2012. On that image, a black-and-white cut-out of the cover, are different typewriter letters, first versions of the fourth and the eighth verse, supplemented with handwritten words. That fourth verse in particular intrigues, where he decipheres:

I stared into the eyes—Ages roll—upon Jupiter & Apollo

Midwivesstroll between jupiter & apollo

Struggling babes past (Between the sheets of . . . Destiny’s faces

miraculous one-eyed glory

The Professor of Classical Literature immediately jumps up: he recognizes almost all – later deleted – words from a poem by Virgil, Ecloge 4, one of the ten shepherds’ poems Virgil publishes around 38 BC. Quite unfathomable poetry, in which the birth of a Saviour is told, a Saviour who will become divine and rule the world. Christians see, of course, a prophetic announcement of the First Coming, of Jesus (but it is more likely that the immodest Virgil uses the birth of a wonderful, divine child as a metaphor for the creation of his own poetry).

The disappointed are in the majority. Not only with the professional critics at the time of publication, but also with the fans, who are still going on in the various forums decades later. On expectingrain, for example. “Vague, disorganized and badly written”, “Bob lost in his own clichés”, “over-written parody”, “embarrassing”, “could have been written by a computer program”, “betrays cocaine abuse”, “confused, portentous self-parody”, “a catalogue of narcissism and mannerism” and one of the most beautiful sentences of all 655720 pages and more on expectingrain’s General Discussion pages : “This song alone should disqualify Dylan from any consideration for a Nobel Prize.”

A harmonica albert writes this in July 2010, six years before Dylan is awarded the Noble Prize.

It cannot entirely be felt, this Guards-bashing. The song is really not that much different from acclaimed classics like “Farewell Angelina” or “Desolation Row”. No recurring line of verse, that may rob the disappointed of a hold. But apart from that? We have come to know and admire the accumulation of seemingly unrelated, strong visual images, the subcutaneous, hazy symbolism and the love for rhyme and rhythm for years. The crowded arrangement, with wind instruments, organ, percussion and ladies’ choir, is perhaps uncomfortable, or at least unusual for the Dylan fan in 1978, but should no longer evoke disgust decades later; the loose, soulful band actually embeds the song in a swinging, pleasant sounding and melodic setting.

Dylan himself is quite fond of the song. He has it released as a single, selects it for Greatest Hits Volume 3 in 1994 and again for another compilation album, for Dylan (2007), and performs it about seventy times in 1978. Invariably as an encore, both in Europe and at all performances at home in America. But the criticism also seems to affect him. He never performs the song again after 1978, not even after he arbitrarily appoints it as a Greatest Hit, and in an interview for Q Magazine (December ’89) the master, when asked, actually slightly criticises precisely this song. Interviewer Adrian Deevoy asks about the songs on the recently released Oh Mercy:

Dylan himself is quite fond of the song. He has it released as a single, selects it for Greatest Hits Volume 3 in 1994 and again for another compilation album, for Dylan (2007), and performs it about seventy times in 1978. Invariably as an encore, both in Europe and at all performances at home in America. But the criticism also seems to affect him. He never performs the song again after 1978, not even after he arbitrarily appoints it as a Greatest Hit, and in an interview for Q Magazine (December ’89) the master, when asked, actually slightly criticises precisely this song. Interviewer Adrian Deevoy asks about the songs on the recently released Oh Mercy:

AD: Have you made your lyrics consciously less cryptic?

BD: Well, uh, no. You see these songs weren’t consciously anything. They were mostly just streams-of-consciousness stuff.

AD: But is being cryptic in your writing something you’ve veered away from? Songs like Changing Of The Guard on Street Legal.

BD: Yeah. Maybe. Maybe. We used to do that song Changing Of The Guard quite a few times, quite a bit a few years ago. And the more we did it, the less cryptic it became.

AD: How do you mean?

BD: Doing it night after night, it becomes a lot less cryptic to the person singing it.

AD: What? Less cryptic to you?

BD: To me, yeah.

AD: It’s a very dream-like song.

He nods vigorously.

BD: Yeah, yeah… (Then reconsiders) It could have used some editing a song like that.

On the contrary, an admirer like Prof. Thomas would say: Dylan’s refining, planing, and polishing only diluted the Virgil references. Moreover, one may wonder to what extent the song is cryptic, to what extent the words have a hidden meaning. More obvious is the observation that the poet, as is often the case here, is initially guided by the sound of the words, which fill his creating mind in a stream of consciousness, in a continuous stream of thoughts, without clear logic. And apparently uncoordinated Biblical scenes, memories of Virgil and less grand images pop up.

The black nightingale, for example. Although black nightingales do not exist, the association itself is not too difficult to grasp. A nightingale sings at night, it is a night bird, the prefix “night’ automatically leads to “black” anyway, and besides that the music fan Dylan has often come across the metaphor as a nickname for a black singer. Belle Fields, who causes a furore from the 1890s to the 1920s especially in Europe (Norway, The Netherlands, Germany), is the best known, but also a Miriam Makeba sometimes gets that name, just like the nurse Mary Seacole (1805-1881), a coloured colleague of Florence Nightingale.

That does not shed any light on an alleged hidden meaning of the verse in question, or of the lyrics at all. But nevertheless (or perhaps partly because of that) it is a beautiful, poetic passage: A messenger arrived with a black nightingale / I seen her on the stairs and I couldn’t help but follow.

The same applies to a text fragment like mountain laurel and rolling rocks. A verse later the poet paraphrases Matthew 17:20 (in which Jesus says that faith can move mountains) with I’ve moved your mountains. The association with the pleasant assonating mountain laurel and the classic alliteration rolling rocks is easily made, but of course it tells nothing. “Mountain laurel” is the somewhat misleading name for calmia latifolia (so actually spoonwood broadleaf). The plant is pretty poisonous and widely distributed throughout almost the entire eastern United States. Dylan will therefore mainly have chosen it because of that pleasant assonance, but in addition, “mountain laurel” also suggests something with mythical struggle, heroics, with ancient legends. And fits beautifully within a text in which besides Bible fragments and shavings of Roman culture also hints of folklore must provide the colour. After all, the witches, shoeshine and the Rapunzel-like scene, including long blonde locks, provide some archaic, European fairy tale colour – and a mysterious mirroring with the closing song of Street Legal, with “Where Are You Tonight?”

Surely, a protagonist singing “I climbed up her hair” and “clutching to golden locks” really can only be referencing that tragic long-haired beauty… or maybe, maybe the poet just succumbs to the rhythmic beauty and the vowel harmony of on to his long golden locks. Which is, indeed, a wonderful finale of this extraordinary, very visual verse:

She wakes him up

Forty-eight hours later, the sun is breaking

Near broken chains, mountain laurel and rolling rocks

She’s begging to know what measures he now will be taking

He’s pulling her down and she’s clutching on to his long golden locks

Equally evocative are the incomprehensible tarot references, with which Dylan apparently aimlessly interlaces the song. The aforementioned Jonathan Cott, who often speaks with Dylan between the end of ’77 and September ’78 and publishes two interviews in Rolling Stone, drones on about all the tarot symbolism he discovers in “Changing Of The Guards”. The Moon, the Sun, the High Priestess, the Tower and of course the King and the Queen of Swords from the final line can all be found on tarot cards and the all too eager Cott does have theories. But Dylan rejects them all, slightly embarrassed, as it seems. “I’m not really too acquainted with that, you know.” Three years later, in an interview with Neil Spencer in New Musical Express, he repeats that almost literally: “I don’t know. I didn’t get into the Tarot Cards all that deeply.”

The fruitlessly puzzling cryptoanalysts should comfort themselves with those famous words that the master himself entrusts to interviewer Ron Rosenbaum in November ’77, so in the same weeks when he writes this song:

“It’s the sound and the words. Words don’t interfere with it. They… they… punctuate it. You know, they give it purpose.”

… which he does seem to mean seriously. In his overwhelming Nobel Prize Speech, almost forty years later, repeating again that the sound is more important to him than the meaning of the words:

“[The songs] can mean a lot of different things. If a song moves you, that’s all that’s important. I don’t have to know what a song means. I’ve written all kinds of things into my songs. And I’m not going to worry about it – what it all means. (…) I don’t know what it means, either. But it sounds good. And you want your songs to sound good.”

The Patti Smith version is a small masterpiece. Smith, who also has such a remarkable “Wicked Messenger” to her name, surprises with a driving, inspired cover in a – compared to the original – stripped-down arrangement. Muted drums, a murmuring guitar and modest fillings of a piano and an equally modest second voice from daughter Jesse Paris, but beyond that is the driven, emotion-laden recital of Smith – Patti seems to know very well what she is singing here (on Twelve, 2007).

The contribution of The Gaslight Anthem to the tribute album Chimes Of Freedom: The Songs Of Bob Dylan Honoring 50 Years Of Amnesty International (2012) is generally received favorably, and is even praised in some forums, but really does not match Patti Smith; frankly, the stadium rock arrangement and the acted outburst of singer Brian Fallon bores rather quickly. After all, it is not a Bruce Springsteen song and moreover, we already knew the adrenaline approach from Frank Black, who then at least adds more raw, angular energy to it (All My Ghosts, 1998).

Chris Whitley and Jeff Lang (Dislocation Blues, 2007, recorded half a year before Whitley’s death) are the only ones who can rival Smith. The duo opts for a spectacularly different approach and produces a slow, sultry version with a very attractive, pleasant Delta Blues atmosphere, filled with despair, lost love and regret.

It is a cover that most likely pleases the master too, a cover that brings the song forth from the shadows, to the marketplace.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oKr6nXJoO2M

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

Nice article – the imagistic song as far as I’m concerned is one of Dylan’s best even taking only the assonate and alliterative sounds into account. However, with tongue-in-cheek a bit, I’d equate the general theme with “Won’t Be Fooled Again” – the new boss/guard is the same as the old boss/guard: Zeus(Jupiter)/Apollo; God/Christ.

Well said. There are many more examples of Dylan stating the primacy of performance ( over the words ) including ” When I do whatever it is I’m doing, there is rhythm involved and there is phrasing involved. And that’s where it all balances out…It’s not in the lyrics. It’s in the phrasing and dynamics and the rhythm.”

The inclusion of this song on ‘Greatest Hits ‘ ,etc, I agree, is interesting. It is hard to think of a less Top 40 song …no chorus, no repeating of the words, no 3 minute jingle, a song that demands that you listen intently, a song with phrasing that is unique, a song with a vocal so in tune with the words that it is breath taking… no this is far outside the Top 40 of 1978 or any other time. The magnificent ‘Street-Legal’ was a huge success in Europe especially here in the UK ( ‘Baby Stop Crying’ made the top 10) and Dylan has always been an album artist.

‘Changing Of The Guards’ is one of my ‘go to’ Dylan songs when I want to demonstrate to non-believers his overall genius ( and not just his genius as a singer ) together with ‘ Desolation Row ‘ and ‘Tangled Up in Blue’ amongst others.

This great song sounds today as fresh, captivating and timeless as the day in 1978 when I played the album over and over again.

A very good article and I sympathise with the reactions, but would like to ad that the song is not meaningless to me. The great song evokes many meanings, the many facets of the diamond of truth, through its sounds, rhythm and the delving into images that he has found on the streets, in books and above all in music and juxtaposing them in his unique poetic way, which has made him Nobel worthy. I believe that the unimaginative criticism has led him to abandon this style more than once, which led to the much less poetic and one dimensional songs such as in Slow Train Coming, because, alhough he goes his own way mostly, he can be deeply hurt by the misunderstanding around him, he is human after all…

I meant to write add of course… sorry

I seem to recall finding a website in the early 2000s that interpreted it as being about alien abductions. I don’t really remember the argument.

I believe that when a Bob Dylan song and performance offers this level of creativity then multiple interpretations become possible. I hear something in his singing which is difficult to articulate but conveys to me feelings of loss and regret. Also, the journey the song describes is brilliantly echoed in the galloping, wonderful music. The mournful saxophone and the uplifting backing vocals provide another descriptive element. As terrific as the words and rhymes are, they need Dylan’s musical genius ( and only Bob Dylan ) to enable the song to become alive. It is a Dylan classic.

Great article and a great song … we all have our down ideas about what some of it is about ….Keep up the good work!! Ps ..the musical attachments were excellent too.

Thankful for the depth of material on this website. Agree that this song supports a wide variety of interpretations, and an approach focused on one (or few) aspects necessarily falls short on others.

To me, the song creates some atmosphere of magic (and, judging e. g. by Youtube comments, many fans feel similarly). This, I suspect, would not be the case if it merely alluded to some literary imagery and mixed and obscured those references to make the lyrics vaguely mystical. I feel that this magic comes about because the song touches something deep within that lies beyond the rational mind.

I’d describe this deep aspect as the level of the soul. Originally connected to a higher realm, it has fallen into a world of opposites, suffering, and imitation, and is seeking a way out. To me, the lyrics describe aspects of re-connecting to the original source.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/116/Changing-of-the-Guards

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.