by Jochen Markhorst

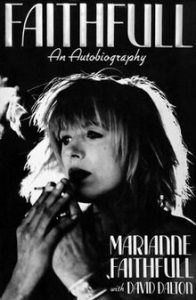

In the end he apparently did get them after all, those boots from Spanish leather. Marianne Faithfull is pretty blown away by the Dylan of the mid-sixties and makes no secret of her crush in a sparkling autobiography (1994). That “proto punk” haircut, , the black leather and the way he talks: devastating. Nobody in London talks like this, over here they all smoke too much hash anyway.

“All that cerebral jangling was a lot sexier than I’d imagined, so it’s not that I didn’t find him attractive. I did. I found him very attractive indeed. I’ve always loved his wiry, coiled type of energy. The impeccable motley tailoring, the Spanish boots, the Rimbaud coif, the druggy shades. All that I adored. I just found him so . . . daunting.”

“Spanish boots”. Referring to boots made of Spanish leather, rather than a specific model. And “Spanish leather” is a somewhat misleading product specification too. Likewise, that is not leather of a certain quality or of a certain origin either, but any piece of leather that is perfumed with Peau d’Espagne, with “skin of Spain”, a popular perfume since the sixteenth century. Rose oil, lavender, sandalwood, cloves, cinnamon and some other ingredients … the recipe has been widely used since the nineteenth century and, after the addition of vanilla and geranium, also becomes popular as a women’s perfume in the twentieth century. But the original peau d’Espagne is, according to legendary sexologist Havelock Ellis (1859-1939), a “very complex and luxurious perfume,” which is said to be “closest to the scent of a woman’s skin” of all perfumes. Often, as Ellis seems to know, “the favorite scent of sensuous persons”, which is again due to the presence of “the crude animal sexual odors of musk and civet” (Studies In The Psychology Of Sex Vol. 4, 1927).

As to why the I-person in “Boots Of Spanish Leather” is yearning for those “Spanish boots of Spanish leather”, Havelock Ellis has an explanation too. There is no doubt, he argues, that the smell of leather has a peculiar stimulating sexual influence on many people. Probably because the scent is somewhere between natural body odors and artificial perfumes. Thus explaining the most common fetish: shoe fetishism. After all, body odor (from the feet) and leather odor (from the shoes) come together there.

Explicitly calling them “Spanish Boots” is a bit weird, though. A “Spanish boot” is actually a rather horrible torture tool. Universal too; in almost every culture of the past thousand years there are variants of a housing that is clamped around the leg and then, with screws or a wedge, compresses the lower leg to such an extent that bones shatter and blood spurts. Incredibly painful, it seems to be.

It is unlikely that the poet refers to this – as a metaphor for love suffering, it is very far-fetched and inappropriately horrific. Presumably, Dylan, like Marianne Faithfull, sees Spanish boots as a quality mark, as an indication of particularly cool footwear.

Less thin, and more relevant in terms of structure and content, is the line to “Black Jack Davey”, which is made by most commentators. That song has been bouncing around the Anglo-Saxon world for some 250 years, with varying lyrics and different titles (“The Gypsy Laddie”, “The Raggle Taggle Gypsy”, “Seven Yellow Gypsies”, “Johnnie Faa”, to name just a few) and tells the story of a Lady who leaves her husband and her rich life out of love for a gypsy. In the oldest version she is enchanted, in other versions abducted, but the punch line is (usually) the same; when the abandoned Lord has tracked her down, she refuses to go back home with him.

Francis Child’s The English and Scottish Popular Ballads feature eleven variations of the song (no. 200, “The Gypsy Laddie”). In most versions the Lady in the third or fourth verse symbolically says goodbye to her rich, pampered life by taking off an expensive item of clothing. A gay mantile, a silken cloak, a fine mantle. Sometime in the mid-nineteenth century the perspective shifts downwards and is it “high-heeld shoes, they was made of Spanish leather”, which Dylan in 1992, on Good As I Been To You, changes into: she pulled off them high heeled shoes, made of Spanish leather. By the way, that is not Woody Guthrie’s version, who opts for buckskin gloves or Spanish leather.

Following the symbolism, the poet Dylan would thus make clear with the abandoned lover’s request: the narrator resides in the final farewell. “Well, then take off your boots of Spanish leather and return them to me,” in other words: leave your current life with me behind, just like the Lady in “Black Jack Davey” does, and depart to unknown horizons, to the country to where you’re goin’:

So take heed, take heed of the western wind

Take heed of the stormy weather

And yes, there’s something you can send back to me

Spanish boots of Spanish leather

Every analyst points to the autobiographical link, to the fact that Dylan’s beloved Suze Rotolo is far away in Italy and how much it hurts him that she is not in a hurry to return (indeed, she does meet her later husband Enzo Bartoccioli in Perugia). In her autobiography A Freewheelin’ Time – A Memoir Of Greenwich Village (2008), Rotolo writes sans rancune, with an attractive mix of down-to-earthness, grace and melancholy about her relationship with Dylan. Her “retreat” in Perugia is also extensively highlighted, the heartache Dylan has, the letters and postcards he writes and she indicates fairly precisely, and with right of say of course, which songs are about her. She even prints parts of the correspondence:

“I had another recording session you know – I sang six more songs – you’re in two of them – Bob Dylan’s Blues and Down The Highway (“All you five & ten cent women with nothing in your heads I got a real gal I’m loving and I’ll lover her ’til I’m dead so get away from my door and my window too – right now”). Anyway you’re in those two songs specifically – and another one too – I’m in the Mood for You – which is for you but I don’t mention your name….

“I wrote a song about that statue we saw in Washington of Tom Jefferson – you’re in it.”

But a few chapters later, Rotolo diminishes the main role Dylan assigns to her again:

“I don’t like to claim any Dylan songs as having been written about me, to do so would violate the art he puts out in the world. The songs are for the listener to relate to, identify with, and interpret through his or her own experience.”

Rotolo does not mention “Boots Of Spanish Leather”, not even indirectly – as, for example, she refers to “One Too Many Mornings” in the chapter Breaking Fame, when she talks about the approaching break-up; that chapter opens with He saw right from his side and I saw right from mine (paraphrasing “You’re right from your side / I’m right from mine”).

Well alright, in his first letter, which she receives at a stopover in Paris, it says that Dylan spent a long time on the quay looking at the departing ship with Suze: he described the ship sailing off – there we have it, a vague echo from the song.

The melody, the music is beautiful enough, obviously; just like “Girl From The North Country” a rip-off from the old “Scarborough Fair”, and thematically it is not that much different from that antique song either.

The essence of the story can already be found in a printed version from 1670, the Broadside ballad “The Wind hath blown my Plaid away, or, A Discourse betwixt a young Woman and the Elphin Knight”, which can be traced back to Oriental sources from centuries older. And variants can also be found at the Grimm Brothers – Die kluge Bauerntochter (“The Peasant’s Wise Daughter”) for example, and Amor und Psyche and Die beiden Königskinder (“The Two Kings’ Children”); all of them stories in which the main character must complete three impossible tasks to prove that he or she is worthy.

The song is a discourse, in this case between a nobleman and a young woman. In the first three verses, the nobleman requires the enamored girl to complete three impossible tasks – sewing a seamless cambric shirt is a constant in almost all variants (the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes includes the song under the heading “Cambric Shirt”). In the following three verses, the maid in turn demands the accomplishment of three impossible tasks – only then the nobleman shall receive his seamless shirt and those other things.

The most famous adaptation, the one by Simon and Garfunkel, undermines the dramatic power. The duo reduces it to a man’s monologue, who six verses long requires everything and anything from that poor girl (again a seamless shirt too, by the way) and in conclusion summarizes:

Love imposes impossible tasks

Parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme

Though not more than any heart asks

And I must know she’s a true love of mine

Dylan’s sense of dramatic construction and psychological depth is better developed than with his medieval predecessors and with Simon and Garfunkel.

For starters: Dylan turns it into a dialogue, which already improves the dynamics a lot. The first six verses alternate between the leaving girl and her inconsolable lover. The lady says goodbye and asks what kind of gift she can send to make the wooer happy. But he does not want anything, just that she returns home as soon as possible. No silver for example, or something of gold? (Money is of no importance, apparently.)

No, neither the stars of the sky nor diamonds from the ocean would alleviate the pain of her absence. “Really nothing at all?” the persistent girl pushes. No, no, all I want is you.

The message of the seventh verse hits the listener almost as hard as the narrator:

I got a letter on a lonesome day

It was from her ship a-sailin’

Saying I don’t know when I’ll be comin’ back again

It depends on how I’m a-feelin’

… that girl is not going to come back at all, and she wanted to appease her bad conscience with that gold and silver, as we now understand.

And he too understands:

Well, if you, my love, must think that-a-way

I’m sure your mind is roamin’

I’m sure your heart is not with me

But with the country to where you’re goin’

Bitter, disappointed, yet pragmatic – pragmatic enough to serve that elegant, heartbreaking closing nugget: ah, there is something you can send me after all. Let’s have those Spanish leather boots.

Covered countless times, of course. Usually beautiful, and otherwise at least tolerable; after all, this song falls into the category Unbreakable. The half premier division succumbs (Joan Baez, Richie Havens, Boz Scaggs, Nanci Griffith), and the divisions below have a go at it too.

As is often the case, the lonely ladies with just guitar have the certain je-ne-sais-quoi. Kiersten Holine is an excellent, heartbreaking example.

The solo album from Dan McCafferty, the singer of the Scottish rock band Nazareth, who often displays his admirable talent for upgrading songs (“Love Hurts”, the Stones’ “Out Of Time”, and especially Joni Mitchell’s “This Flight Tonight”). McCafferty’s Boots is embellished by a full band and yet modest, pleasantly melancholic and powerful – actually exactly what Rod Stewart in his best days would have made of it.

However, most of the goose bumps are produced by the North Carolina folk duo Mandolin Orange with a simple and irresistible trick: the enchanting violinist Emily Frantz sings the ladies’ part, guitarist Andrew Marlin the abandoned lover – and the one line they sing together (“I don’t know when I’ll be comin’ back again”) is pure magic.

That violin solo, by the way, would even break Suze’s heart way over in Perugia.

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

Bob Dylan’s grandfather had a shoe factory in Odessa Ukraine. The family fled away from the pogroms 1905. In the poem “I and I” he wrote: “I have made shoes for everyone, even you, while I still go barefooted”. Shoes/boots symbolize his profession. Spanish symbolizes love. “Spanish is the loving tongue” is the title of another song. Spanish boots symbolize love songs.The boots are also a symbol of travel or escape. The boots did not bring her back to him, instead she used them for escaping.

Ups is he a little naughty If leather refers to the skin, then spanish leather might refer to erotic love and not to romantic love.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/90/Boots-of-Spanish-Leather

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.