by Jochen Markhorst

Oh, I think of myself more as a song and dance man, y’know.

Oh, I think of myself more as a song and dance man, y’know.

At the same press conference in San Francisco (December 3, 1965) where he declares that Manfred Mann is the best interpreter of his songs, Dylan defines himself as a song and dance man, as a troubadour, or: a minstrel. He postulates it with a boyish, charming grin, still smiling when he has to repeat it, but he does mean it, as we know by now.

Already in “Talking New York”, the first Dylan song which the world gets to know, he introduces himself as a traveling musician, and hereafter he keeps reminding us. I just walk along and stroll and sing, he sings in “I Shall Be Free”, I am a wandering song singer, he tells in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall”, in “Eternal Circle”, in “I Shall Be Free No. 10”, he is a Mr. Tambourine Man following the music in “Farewell Angelina”, is stoned for his songs in “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35”, and in the 21st century, on Tempest, the I still enters the scene singing and dancing: bring down my fiddle, tune up my strings.

The Traveling Wilbury’s, the supergroup in which Dylan is “Lucky Wilbury”, explicitly present themselves as minstrels too, in the attached, fictional provenance: “Dim Sun, a Chinese academic, argues that they may be related to The Strolling Tilburys, Queen Elizabeth the First’s favorite minstrels.”

And on the first record of The Traveling Wilbury’s, former Monty Python Michael Palin concludes that the group’s origins can be traced back to a culture shift at the originally very sedentary Wilbury’s:

Some intrepid Wilburys began to go away for the weekend, leaving late Friday and coming back Sunday. It was they who evolved simple rhythmic forms to describe their adventures.

Minstrels, in short. It therefore seems likely that Dylan came across his nom de plume “Lucky Wilbury” via this bridge. Through his oeuvre dozens of roaming musicians, troubadours and minstrels do march, but only one of them gets a name:

Oh, Lucky’s been drivin’ a long, long time

And now he’s stuck on top of the hill

… the minstrel Lucky in “Minstrel Boy”. Dylan shakes this charming song from his sleeve during that carefree summer of 1967 in the Big Pink, as he goofs around with the guys from The Band, filling the spectacular Basement Tapes. The world only gets acquainted with the song thanks to the live recording of the Wight concert, which ends up on Self Portrait.

At that point it is still unclear whence the song comes, but when Writings & Drawings is published in 1973, it appears that Dylan considers the song to be a Basement Tape. He places the lyrics as a second song in the “From Blonde On Blonde to John Wesley Harding” chapter, on page 364. Immediately after “Quinn The Eskimo”, which opens the chapter with twenty-one Basement songs, and before “Down In The Flood”.

At that point it is still unclear whence the song comes, but when Writings & Drawings is published in 1973, it appears that Dylan considers the song to be a Basement Tape. He places the lyrics as a second song in the “From Blonde On Blonde to John Wesley Harding” chapter, on page 364. Immediately after “Quinn The Eskimo”, which opens the chapter with twenty-one Basement songs, and before “Down In The Flood”.

Apparently Dylan has been brooding on the song some more: it is one of the fifteen chosen songs for which he makes a drawing. These Basement songs inspire him disproportionately often anyway. Five times, the Basement songs get five drawings – the lyrics of the ten other chapters, the chapters that are hung on the ten official albums, have on average only one drawing each.

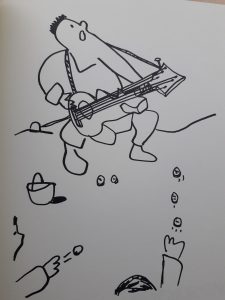

Compared with most of the other fourteen drawings, the scribble to “Minstrel Boy” is quite one-dimensional. A boy with a guitar is thrown coins, so it is really no more than an awkward illustration of the first verse (Who’s gonna throw that minstrel boy a coin). Although … that rope or string from the guitar to a stone (?) behind the minstrel is strange. Is the minstrel tethered? Or is it perhaps a cable, does Lucky play electrically amplified?

It is almost inevitable to interpret the song autobiographically. From day one, Dylan presents himself as a song and dance man, and here he sings, after those tumultuous years ’62 -’66 of non-stop recording, tours, cheers and booing, hysterical raving, idolatry and mud-slinging, about a musician who, after having been on the road for a long time, now has crashed. Feeling – despite all the female attention – lonely and burdened. And moreover: in the last verse, Dylan suddenly switches from the third person to the first person and sings: I’m still on that road.

Mysterious, however, is mainly the third line of the first verse, the line that only exists in writing. In terms of content, the words are quite uncomplicated. With twelve forward gears, it’s a long hard climb – so that was a trip with a pretty heavy truck or a big tractor; the poet finds a fresh metaphor to express that it certainly has not been a lazy-on-a-sunny-afternoon ride, those years on the road.

No, the mystery lies mainly in the question: where does that line come from? Neither on the very fragmentary and sketchy Basement recording from 1967, nor on the Wight 1969 live recording those words can be heard. On Wight Dylan sings something like with aching jumpers, with all on down or maybe well aching and jumping with all laid down, words, anyway, that have nothing in common with the line that is written in Writings & Drawings and again later in The Lyrics and on the site.

Curious, moreover, is the effort Dylan has made to insert these, otherwise little spectacular, words and protect them under copyright law. It seems to contribute next to nothing to the song’s expressiveness, and anyhow, it is a song Dylan will never look back on – the one performance in ’69 is also the last one.

At the release, on the maligned Self Portrait, the song yields the very rare nice things that are said and written about the album. Even headsman Greil Marcus steps out of character for a second, in his infamous What is this shit review (Rolling Stone, June 1970): “Minstrel Boy is the best of the Isle of Wight cuts; it rides easy.”

And apparently the song is appreciated by the audience too; on the recording one can hear how the listeners after the first line move from words to deeds and throw the minstrel coins – clattering at his feet, at the microphone stand.

This exceptional position, which the song only shares with “Copper Kettle”, is somewhat maintained over the years. “Minstrel Boy” is occasionally highlighted and appreciated in retrospects, in overview articles and on fan forums in the following decades, in which Self Portrait is slowly reaping some revaluation.

However, the song remains obscure. Apart from a single tribute band, the entire music world follows Dylan’s example: it is never played, biographers ignore it and the song degenerates into a catalog number in the overview lists.

That won’t change until 2013. “Minstrel Boy” is on both The Bootleg Series Vol. 10: Another Self Portrait as on The Bootleg Series Vol. 11: The Basement Tapes Complete and, sure enough, is picked up by artists like Robyn Hitchcock and Dave Rawlings, who bring the song to the stage once in a while.

More admiration deserves Jolie Holland, the New Weird American who previously has dusted such a wonderful “Tell Me That It Isn’t True” on The Lagniappe Sessions (2014). In 2017 she releases the beautiful Wildflower Blues with her old bandmate Samantha Parton, which besides a very nice cover of Townes Van Zandt’s “You Are Not Needed Now” also contains the greatest cover of “Minstrel Boy”.

The ladies think the song is a bit too short, though. Jolie is bold enough to write two extra couplets, which by the way fit perfectly. They call their music North Americana and outsider folk, a self-invented genre designation that actually does justice to their oeuvre perfectly; their “Minstrel Boy” is a sensual, lazy-sunny-afternoon performance with superior singing by the ladies. They do deserve a lot of coins.

Jolie Holland & Samantha Parton:

What else is here?

An index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

There is an alphabetic index to the 550+ Dylan compositions reviewed on the site which you will find it here. There are also 500+ other articles on different issues relating to Dylan. The other subject areas are also shown at the top under the picture.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook which mostly relates to Bob Dylan today. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews.

My absolute favorite version of Minstrel Boy has to be Joe Strummer’s take from the Black Hawk Down soundtrack. Stunning.

https://m.youtube.com/watch?v=8PSTus_5bl8

He also included an 18 minute version on his Global A Go Go album. It’s breathtaking

… which has no further relationship with Dylan’s song of the same name (to avoid any misunderstanding).

I can’t help it if I’m Lucky!

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/412/Minstrel-Boy

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.