by Jochen Markhorst

“Elvis,” Dylan replies to the question by whom he likes to hear his songs covered, “Elvis Pres ley recorded a song of mine. That’s the one recording I treasure the most of all… it was called Tomorrow Is A Long Time” (Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner, November ’69).

ley recorded a song of mine. That’s the one recording I treasure the most of all… it was called Tomorrow Is A Long Time” (Rolling Stone interview with Jann Wenner, November ’69).

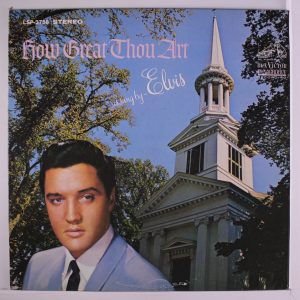

In May 1966, shortly after Dylan completed the recordings for Blonde On Blonde, Presley enters the RCA Studio B in Nashville to record in four days eleven of the twelve songs for his second gospel album, How Great Thou Art. Partly with men who have just assisted Dylan, by the way; both Charlie McCoy and bass player Henry Strzelecki are on the payroll. The twelfth song, the final song (and the hit) “Crying In The Chapel” was recorded by Presley in 1960 and was released as a single in 1965.

The album with the twelve songs will only be released half a year later, in February ’67, but in between Spinout (October 1966) appears, on which The King sings two songs which have been recorded on May 26, 1966, the second recording day of How Great Thou Art: “Down In The Alley” and that most valuable compliment that Dylan has ever received, “Tomorrow Is A Long Time”, which Presley knows through the version of Odetta.

Dylan’s love for Elvis is deep and well-documented, as is his attachment to gospel. “Songs like Let Me Rest On A Peaceful Mountain or I Saw The Light are my religion,” he confesses in the Newsweek interview (1997). And in the acclaimed MusiCares speech in 2015, he aloud dreams of the plan to record a whole gospel album with the Blackwood Brothers. Again an Elvis connection: the Blackwood Brothers are Presley’s favourite gospel quartet. For his first gospel album, he plunders their repertoire (“His Hands In Mine” and “In My Father’s House”, among others), he has been friends with the family since the early 1950s, copies the Blackwood logo font on his first two gospel records, often invites the brethren to Graceland and also performs with them once. The title song “How Great Thou Art” Elvis learns from the brothers too, by the way (and James Blackwood will sing the song again at Elvis’s funeral). And the other classic that connects Dylan and The King:

“One of the songs I’m thinking about singing is Stand By Me with the Blackwood Brothers. Not Stand By Me the pop song. No. The real Stand By Me.” And then Dylan quotes the entire song lyrics – “I like it better than the pop song.”

On Presley’s How Great Thou Art, “Stand By Me” is the fifth song, recorded one day before “Tomorrow Is A Long Time” – a lot comes together on this album for Dylan. Undoubtedly, How Great Thou Art has often been on the turntable in Hi Lo Ha, in Dylan’s house that spring of 1967. And echoes thereof resonate a few months later in the Basement of the Big Pink, where Dylan plucks his first own gospel song from the air: “Sign On The Cross”.

It is a remarkable song, rightly praised as one of the absolute highlights of the Basement Tapes, on the same level as “I’m Not There” and “I Shall Be Released”. And just like “I’m Not There”, and many more Basement songs, the song emerges rather spontaneously. Witness from the first hour Garth Hudson confirms this, in the moving Rolling Stone documentary (November 2014), in which he visits the Big Pink again for the first time in almost fifty years. The old Hudson slowly shuffles around, sits musing at the piano and shares his memories, including about “Sign On The Cross”:

“Bob didn’t like to sing the same song over and over again. Sounds to me like he did make up songs on the spot. (…). I think “Sign On The Cross” was done in real time. Both the composition and the execution thereof.”

So the lyrics have been improvised on the spot and are accordingly inconsistent, partly unintelligible, and appear to be a huddle of fragments of Blackwood, Bible and Luke The Drifter.

Key to the Kingdom, for example, echoes the song of the same name from the Brothers. Your days are numbered is a Bible phrase (from Job and from Daniel) with which Dylan has something anyway – he already uses it in “When The Ship Comes In” and will later use it again in “Mississippi”. And the spoken sermon part is unmistakably Luke The Drifter, Hank Williams’s alter ego. “Men With Broken Hearts”, “Be Careful Of The Stones That You Throw” (the song the men also play in the Basement these days), “Too Many Parties and Too Many Pals”, which is added to radio maker Dylan’s Theme Time Radio Hour’s playlist forty years later, “The Funeral”, “Help Me Understand” … all those songs with rhyming sermonettes, talk-sung sermons, that Dylan has under his skin and of which he copies the drawling diction, the rhythm and the vague Southern accent for this part of “Sign On The Cross”.

Initially, goofiness undoubtedly triggered the song’s creation. In the first part, the first three couplets, Dylan is still flawlessly in Buster Keaton mode. He sings free of irony, wistful, almost falsetto, carried by the particular heavenly organ playing of Garth Hudson and the stately cadence of the song. Once at the sermonette, the bard does not completely succeed in keeping a straight face and one can hear the corners of his mouth curl up. Gradually, the (not very successful) Southern accent creeps up stronger, but: his talent for improvisation and his self-control do not let him down and he completes the sermon without exploding.

In terms of content, it is far from coherent, but a single, almost-rounded, aphoristic gem does shine. The door is here and you might want to enter it, but, or course, the door might be closed stands out. Luke The Drifter loves parables, but this one seems to be inspired by one of Kafka’s most famous: Vor dem Gesetz, “Before the Law”, the parable told to Josef K. in Der Prozeß (The Trial) by a preacher. Herein, the main character arrives at “The Law”. He wishes to gain entry, but the Türhüter, the Doorkeeper, does not let him in and lets the man wait for years, until his death, at the door to the Law. You might want to enter it, but the door might be closed.

It is, with all its beauty, slightly frustrating. The perfect, unearthly musical accompaniment, Dylan’s breathtaking vocals, the rough poetic diamonds, the enigmatic concept sign on the cross … the brilliant, boundlessly inspired song poet Dylan from 1967 needs at most half a typewriter session to create a definitive masterpiece in the outer category, another “Desolation Row” or “Visions Of Johanna”.

But he shrugs it off. It is unknown why he discharges the song without comment, does not grant it a second take or at least performs it again on stage. Perhaps he does not feel completely at ease with the unserious approach of a religious song, or he fears that he is not able to oversee the impact of the chosen images (although this does not stop him a bit later, in the songs for John Wesley Harding). And, more importantly, the words mean nothing, have no coherence, and merely suggest an evangelical message.

In any case, in January 1974, just under five years before his much talked-about conversion and the ensuing deadly serious gospel songs, Dylan claims that religion does not go too deeply for him:

“Religion to me is a fleeting thing. Can’t nail it down. It’s in me and out of me. It does give me, on the surface, some images, but I don’t know to what degree.”

That is quite different for Elvis, for whom gospel, experience of God and religion are deeply, deeply rooted in his genes. But even Elvis has reserves: at a concert in 1955 where the Blackwood Brothers are also performing, he refuses to sing rock ‘n’ roll songs – out of respect for his idols.

Eventually it will take until 1973 before Roxy Music fills the gap and lets a gospel song flourish in a pure rock environment, with the masterpiece “Psalm” on the Stranded album. Admittedly steeped in the famous Bryan Ferry irony, but still…

“Sign On The Cross” is not one of the fourteen songs offered to other artists on the “publishing demo” in 1968, nor is it on the first bootlegs Great White Wonder (’69) and Great White Wonder II (’70). The song is still unknown when copyright is established in 1971.

In 1972 the song finally comes to the surface: on one of the best Dylan tribute albums ever, on Coulson, Dean, McGuinness, Flint’s Lo And Behold! from England, produced by the Supreme Guru of the Dylan covers, Manfred Mann.

It is a wonderful version. Dennis Coulson is from Benwell, Newcastle, Tom McGuinness from Wimbledon, Dixie Dean lives a few miles away in New Malden and drummer Hughie Flint was born and raised in Manchester – on paper the men are thoroughly English. But they do hide that very well. The moment their “Sign On The Cross” starts, the listener is in a wooden church in the Alabama countryside. First only a subservient piano and a modest bass behind the sensitive, fragile vocals of Dennis Coulson, in the second verse drums and accordion join in and the guitar of McGuinness places tasteful, lyrical decorations (more beautiful than Robbie Robertson’s exquisite Curtis Mayfield licks of the original). In the third verse the brakes are released. The band switches to an irresistible blues stomp with a grand ladies choir, to switch back just before the sermonette. Coulson is too wise to get caught in such a sermon; that would indeed break the spell. Instead, the men let Jimmy Jewell, the saxophonist to whom we also owe that short, heart-warming sax solo in Joan Armatrading’s “Love And Affection”, toot a dry, melancholic solo. Then all the obligations are met and the men, supported by the enthusiastic background singers, can let their freak flags fly. The song ends as it should end: furious, uplifting and above all soulful.

Elvis could not have done it better.

Postscript: For once we are unable to offer online videos of the cover version that is cited here. Coulson, Dean, McGuinness, Flint’s version of the song may of course be available in your location. But if not and you want to hear it you will either have to subscribe to an obliging subscription service or else try and find a copy of the Lo And Behold! album in an obliging store.

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/566/Sign-On-The-Cross

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.

Because later onyou might find the door

You might want to enter

But of course the door might be closed