by Jochen Markhorst

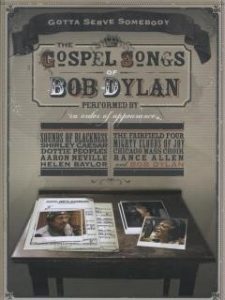

Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs of Bob Dylan from 2003 is a beautiful tribute album on which black gospel artists play eleven, mostly outstanding, versions of Dylan’s religious songs, from songs from the Devout Duo Slow Train Coming and Saved. Producer of both Dylan albums is the seasoned veteran Jerry Wexler, who also contributes to the compelling accompanying DVD with the tribute album, a documentary in which intimates like drummer Jim Keltner and guitarist Fred Tackett talk about their experiences with Dylan.

Gotta Serve Somebody: The Gospel Songs of Bob Dylan from 2003 is a beautiful tribute album on which black gospel artists play eleven, mostly outstanding, versions of Dylan’s religious songs, from songs from the Devout Duo Slow Train Coming and Saved. Producer of both Dylan albums is the seasoned veteran Jerry Wexler, who also contributes to the compelling accompanying DVD with the tribute album, a documentary in which intimates like drummer Jim Keltner and guitarist Fred Tackett talk about their experiences with Dylan.

The interview with the quiet, mild and wise Wexler is a highlight. He remembers the first confrontation with Dylan’s new repertoire and his surprise:

“Looks like we got wall-to-wall Jesus coming. Which didn’t faze me at all. I didn’t care. Because it’s Bob. If he’d wanted to do the Yellow Pages: “Yes Sir. Where you wanna start, with A’s or with Z’s?”

And still, more than twenty years after the recordings, he glows with pride, the man who was at the helm with legends such as Aretha Franklin, Dusty Springfield and Ray Charles, the man who coined the term rhythm and blues to brush away the derogatory name race music.

“To be known as Bob Dylan’s producer … that burnishes the image. So – since I have a normal sense of self-gratification – it has made me very happy from that aspect of it: I went to work with Bob Dylan, and I didn’t fail. (…) Did you see this piece by Sinead O’Connor, saying that this record was the major influence on her life?”

The first song that Dylan writes for his first religious album is not a religious song. “Slow Train” does have that status, partly because Dylan apparently attaches special importance to it and even names the entire album after it. But lyrically the song is definitely an outsider, Dylan chooses a flag which does not convey the cargo. “Slow Train” should be classified in the column that also includes “Mississippi”, “Chimes Of Freedom” and “Changing Of The Guards”; wide-ranging confetti-rains of impressions by an American citizen who connects the private with the universal, who slaloms between satire, reporting, surrealism, aphoristic oneliners and poetry.

Of course, the song is written, at least in a primordial form, well before Dylan’s radical transition to religious music, before the Bible study sessions in Reseda. The poet visits those sessions, allegedly, almost every morning in the first months of 1979, the first introduction to “Slow Train” takes place in December 1978, during a soundcheck in Nashville. An unsuspecting witness from that first hour would place the song appreciably as a bonus track to Street Legal, probably. The opening line, for instance, sounds like an echo of the sigh on “We Better Talk This Over”:

We’d better talk this over: I feel displaced, I got a low-down feeling

Slow Train: Sometimes I feel so low-down and disgusted

And from the same Street Legal song we also recognize the outspoken aversion to hypocrisy and underhandedness: here the poet fulminates against the companions who renounce their principles, the enemy hiding under a “cloak of decency”, bluff champions and “masters of the proposition”, in We Better, he despises the opponent who is two-faced and double-dealing, who is lying and treacherous.

It does not stop there, in terms of atmosphere, tone and content similarity. In “Changing Of The Guards” the protagonist regretfully watches the power-hungry thieves and merchants, in “No Time To Think” he judges, as in “Slow Train”, that profit and commerce control and dehumanize us (“Mercury rules you,” for example) and anyway, the train slowly coming up around the bend reminds us of the leaving train in Street Legal’s album closer: “There’s a long-distance train, pulling through the rain.”

Now, trains are not a new phenomenon in Dylan’s oeuvre, obviously. This is the twenty-ninth officially released song in which a train is passing by, and already from the cover text of Highway 61 Revisited, fifteen years earlier, Dylan’s fascination for the image of the slow train is apparent. That text opens with “On the slow train time does not interfere”, Autumn points a few lines further to the passing slow train and the poet ends the wildly fanning prose text with the concealing revelation that the subjects of the lyrics on this album are somehow about beautiful strangers, Vivaldi’s green jacket and the holy slow train.

True, it is a beautiful, strong cast-iron image, the image of the train slowly appearing around the bend. In this song text more threatening, darker, more apocalyptic than we know from Dylan. Initially, in the early 60s, the train was a “normal” symbol for romantic Wanderlust, the romantic motivator of the storyteller who hopes to find happiness beyond the next mountain. “Poor Boy Blues”, “Gypsy Lou”, “Paths Of Victory”, to name just a few. Gradually the image of the train becomes a stage piece, to illustrate the detachment of the protagonist, for example. Like in “It Takes A Lot To Laugh” and “Visions Of Johanna”.

Ominous the trains become not until the 70s. Nightly heat hits him with the devastating power of a freight train in “Simple Twist Of Fate”. In “Señor” the last thing the undressed, kneeling narrator sees (incidentally a copy of the execution scene on the last page of Kafka’s The Trial) is “a trainload of fools” and in the stage talk with which Dylan always announces this song in 1978, the singer recounts about a train journey where an old Mexican with devilish features is in his coupé:

“He was just wearing a blanket, and he must have been 150 years old. I took another look at him an I could see that both his eyes were burning out. They was on fire. And there was smoke coming out of his nostrils.”

Now there’s a fellow passenger who raises questions about the travel destination. Certainly not a mousy commuter on his way to his work in the Bookkeeping & Accounting Department, at any rate – rather a demon on his way to Armageddon.

This slightly bewildering speech Dylan delivers around the same time as he writes “Slow Train”, and the mood sets the tone. The seven verses end with the recurring verse in which the slow train is comin’ up around the bend, always preceded by dark observations. But then again, if this song is to be the standard-bearer of Dylan’s first religious album, one could, with some good will, tick off those dark observations as manifestations of Biblical Deadly Sins – such as pride, greed, and gluttony. Still – analysis from an author like Howard Sounes (Down The Highway, 2001), experiencing “a resurgence of faith in God” does seem rather exaggerated.

The first verse and most other verses exude the preachiness of New Testament Bible books, especially the Book of James, although Dylan refrains from quoting literally. Earthly principles is such a concept that, although it sounds mighty Biblical, is nowhere to be found in the Book of Books. The tone of lines like Have they counted the cost it’ll take to bring down / All their earthly principles they’re gonna have to abandon? on the other hand, most certainly is. It does sound quite like the many exhortations that earthly wealth, treasure and riches are fleeting, a chorus with the Apostles and New Testament letter authors.

The same edifying tone colours the fourth, fifth and sixth verse. Evangelically normative, or at least clear and unambiguous the content is not. Such as why Founding Father Thomas Jefferson turns over in his grave. In his time, the author of the Declaration of Independence made quite a point of the principle that all people are equal, so he will indeed be bothered by fools, glorifying themselves. But still… would that result in restlessly tossing around in his last resting place? Jefferson has had his fair bit of experience with those kinds of people, the occurrence of self-elevating idiots two hundred years later can hardly be grave-shakingly shocking.

More focused is the venom that is poured out over the sinners in the fifth and sixth couplet: capitalist big shots, false healers, hypocrites and big-earning television evangelists should prepare for what’s coming, because the holy, slow train is already peeking around the corner.

The vastness and the exaltedness of those couplets is diminished in the two couplets in which the poet gives way to private concerns with ladies from Alabama and Illinois. Both images suggest something anecdotal, but the precise nature of it remains (naturally) Dylanesque foggy.

Yet, even added up these six verses raise fewer questions than that weird third verse. The tone thereof is remarkably different. A xenophobic, agitprop-spreading populist provocateur speaks up, here the poet assumes the role of a redneck uncomfortably close to unhealthy nationalism. “Facts” are stated with a Trump-like aplomb and inaccuracy. That control by foreign oil is really not that big a deal, for example. The United States has been producing more than half of its oil requirements itself for many years and there is still lots of stretch in that need. The image of sheikhs walking around waving chic jewels and wearing nose rings (?), determining America’s future, is downright nasty and malicious, and does awkwardly resemble some demagogue’s fit, rather than a poet laureate’s well-considered reflections. Odd.

The song can stand it, this weird glitch. “Slow Train” is a grandiose song, a magnificent conclusion of that wonderful side A. Guitarist Mark Knopfler may claim a part of the success. He opens with a short solo that is both venomous and lyrical, gets all the space to place accents, exclamation marks and commentaries with every line of verse, and has the talent and skill to enrich the already so rich song. Crackling production by Wexler, great arrangement with modest keyboards and subdued horns … the song crowns one of the most beautiful album sides from Dylan’s rich discography.

The guildsmen, however, stay away from this highlight, oddly enough. There are hardly any covers of “Slow Train”, and certainly not any worth mentioning. The song seems to fall between two stools. Artists who are attracted by the Biblical power of an “I Believe In You” or a “Gotta Serve Somebody” miss the confession here, while others may be deterred by the religious connotation. Anyway: in that original version alone – and also in the live version with Grateful Dead on the wrongly denounced album Dylan & The Dead (1989), by the way – the song will be with us, yes, to the End of Time.

Rotterdam, 1987 (with Tom Petty & The Heartbreakers):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dog4tPL3UZQ

What else is on the site

You’ll find an index to our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to the 500+ Dylan compositions reviewed is now on a new page of its own. You will find it here. It contains reviews of every Dylan composition that we can find a recording of – if you know of anything we have missed please do write in.

We also have a discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

Dylan’s ‘slow train’ does refer to the Holy Bible which points out that the locomotive coming up around the bend actually carries the Queen of Sheba along with camels, spices, gold and gems that she presents to King Solomon:

And she came to Jerusalem with a very great train

With camels that bare spices, and very much gold, and precious stones

And when she was come to Solomon

She communed with him of all that was in her heart

(1 Kings, 10:2)

The King (whose slaves built the railroad tracks to his own gold mine) had become corrupted, and gladly ordered his slaves to unload the Queen’s gifts of camels, spices, gems, and gold from the boxcars.

Very good article once more. And it explains why it is one of the few songs (When He Returns is another, but for opposite reasons cause it is a pure Gospel and not a fingerpointing song) that I really admire from that sterile and sometimes, in my humble opinion, downright nasty album which the great Wexler could not save. I am very fond of Street Legal, because of the poetry in it, although sometimes there as well, Dylan sounds a bit too pissed off, but with humour and some healthy self-mockery, and Slow Train was written shortly thereafter and bears resemblances and has as a surpluss a tremendous funky vein running through it. What I don’t understand is the often blindly repeated criticism about so called racism when he is singing about the oil sheiks. I have witnessed what those guys did to the world in the seventies, and their description rings true to me, by the way, they still cause trouble, one look at the Saoudi should suffice, and it is their power and greed and ugly way of handling women and spreading fundamentalism that is still causing a lot of trouble… It’s not their blood, it is their doing, it has nothing to do with race, but believes and richess.

As well as the singing the ‘phone book quote, Jerry Wexler also said ” there are three geniuses in music Aretha, Ray Charles and Bob Dylan “. I would have therefore expected some kind of recognition of Dylan’s vocal performance on both the album version and the magnificent 1987 live version above. Thankfully, there are no cover versions !

This great song ( what a tune! ) needs Dylan’s genius to sing… the urgency of his voice, the timing and phrasing including the way he effortlessly sings the overly long lines, the understated way he sings the evils described, the masterly way he rhymes “embarrassed” and “Paris”, “companions” and “abandon” and, magically, “stop it ” and “puppets”. The slight changes in the repeated last line , “slow, slow train…”. The timbre. The authority in his voice.

Jerry Wexler’s compliment that Dylan could sing the Yellow Pages is a truly wonderful compliment and gives you some idea of how Bob Dylan’s singing is regarded. I hate lists but the fact that Dylan is in Rolling Stone’s top ten greatest singers, chosen by other singers, is an important statement. I guess Tony included the tremendous live version from Rotterdam, 1987 and this performance can be found on ‘Another Night :Unreleased Recordings ‘ on the great ‘A Thousand Highways’ website.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/576/Slow-Train

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.