by Jochen Markhorst

In December 2016, a remarkable story with a suspiciously high urban legend quality bounces around through the media worldwide. In a television program, the Japanese Otou Yumi talks to his wife for the first time after 20 years of remaining obstinately silent. He felt ignored, he explains, because his wife Katayama gave all her attention to their children and out of jealousy he therefore punished her with silence.

In December 2016, a remarkable story with a suspiciously high urban legend quality bounces around through the media worldwide. In a television program, the Japanese Otou Yumi talks to his wife for the first time after 20 years of remaining obstinately silent. He felt ignored, he explains, because his wife Katayama gave all her attention to their children and out of jealousy he therefore punished her with silence.

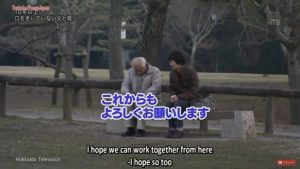

In the Hokkaido TV programme both sit on a bench in the park where they once had their first date. At a distance, hidden behind trees, the three now grown-up sobbing children witness how father talks to their mother for the first time in all those years. “Somehow it has been a while since we talked to each other,” the cowered Otou opens the marital conversation, staring at his feet.

Silent treatment it is called, and for the associative, playful language artist Dylan the jump to the similarly sounding silent weekend is not that big. It is a destructive, passive-aggressive form of punishment and generally quite popular with relational quarrels to effectively express disapproval or contempt. It does bother the I-person from “Silent Weekend,” in any case. What he did or did not do is less clear – the song poet does not elaborate and leaves it at this sketchy, difficult to understand draft.

From the official lyrics can be concluded that the narrator, just like Otou Yumi, finds it annoying that his sweetheart has no attention for him, she is swinging with some other guys. Apparently he vented his dissatisfaction, perhaps against previous agreements about letting each other free. Or misplaced jealousy led him to vicious and unreasonable comments. And that is precisely why, just like Mrs. Katayama Yumi, he gets the cold shoulder. According to the official lyrics, as it is published in Lyrics and on the site:

Silent weekend

My baby she took me by surprise

Silent weekend

My baby she took me by surprise

She’s rockin’ and a-reelin’

Head up to ceiling

An’ swinging with some other guys

However, this October day in 1967, Dylan definitely does not sing about other guys in that second verse. What he does sing is not very clear, but it certainly is something completely different. Tony Attwood and Eyolf Østrem respectively hear something like:

Silent weekend

My baby she took me by the heart

Silent weekend

My baby she took me by the heart

She’s thinkin’ about disposin’

But I know I know she’s dozin’

And she’s tearin’ me all apart

… and Østrem:

Silent weekend,

My baby she took me by the heart.

Silent weekend,

My baby she took me by the heart.

She’s awake and bad, she’s boastin’

but I know I know she’s ghostin’

An’ she’s tearin’ me all apart.

Anyway, in both variants it seems more likely the narrator was caught with other ladies and subsequently has been put in the fridge. In the bridge he admits that he has done a whole lotta thinkin’ about a whole lotta cheatin’, and the mysterious metaphor in the (later rewritten) line to open up a passenger train seems to refer to Jimmie Rodgers’ mega hit from 1928 “Blue Yodel No. 1 (T For Texas)”:

‘Cause I can get more women

Than a passenger train can haul

“Blue Yodel No. 1” was at the time a rather startling mix of folk, blues and jazz, which soon got the somewhat derogatory stamp “hillbilly”, but with some tolerance can be seen as a precursor to rockabilly, and consequently also to rock ’n’ roll. And that, playing a rockabilly tune, is also the raison d’être of “Silent Weekend” – not so much the poet Dylan’s need to encapsulate a universal relationship problem in poetic words. And like “Dress It Up, Better Have It All” seems to pop up from shreds of Carl Perkins, Wanda Jackson and Billy Lee Riley, this rocker too seems, apart from Jimmy Rodgers, to be indebted to the legendary Sun recordings of the 50s. “Lonely Weekends” by Charlie Rich being an obvious candidate:

Well I’m makin’ alright

From Monday morning till Friday night

Oh, those lonely weekends

Since you left me

I’m as lonely as I can be

Oh, those lonely weekends

And not just a source of inspiration in terms of lyrics – “Lonely Weekends” is a beautiful rocker, driven by a rolling piano and a Charlie Rich who is more Elvis-like than ever. Released in 1960 and Rich’s only Top 30 hit in those years (Charlie Rich is on the Sun label until 1963, also earning a living as a session musician for competing colleagues such as Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis and Billy Lee Riley). Forty-seven years after “Silent Weekend”, Dylan professes his love for “Lonely Weekends” in public, when he plays it in episode 53 of Theme Time Radio Hour (“Days Of The Week”): “And one of my favourite songs about the weekend is from the Silver Fox, Charlie Rich.”

The return of Levon Helm must have been a trigger. Almost two years before, November 29, 1965, the sensitive, gentle Helm said goodbye to the group, battered and bruised by the audience’s hateful booing during the world tour, and perhaps also in dissatisfaction with his supporting role as “the drummer of Bob Dylan’s backing band”. But in the late summer of ’67, Albert Grossman becomes the manager of the then-nameless band and arranges (eventually, a few months later) a record deal with Capitol. Rick Danko already sees the Big Money Ship on the horizon, and thinks that Levon should get the hell back in order to catch his drop of the honey pot. “They want to give us a couple hundred thou, Lee. Better come and get your share!” (in The Last Waltz of The Band, Neil Minturn, 2005).

The band has been in Woodstock since February, has been playing all those wonderful old and new songs for months, from June been recording all those bizarre, traditional, incomparable and everyday songs, and Levon is delighted:

“They played me some of these tapes, and I could barely believe the level of work they’d been putting out. (…). I could tell that hanging out with the boys had helped Bob to find a connection with things we were interested in: blues, rockabilly, R&B. They had rubbed off on him a little.”

(This Wheel’s On Fire, 1996)

Dylan’s “found connection” with blues and rockabilly is arguably a bit older than this summer in Woodstock, but it’s understandable that Levon’s heart skips a beat. Helm is the only real rockabilly veteran here in this basement; he plays drums in the original Hawks with Ronnie Hawkins as early as 1958 and records “Red Hot” with him (on the first album Ronnie Hawkins, 1959).

Levon has just missed the previous exercise, “Dress It Up, Better Have It All,” but Dylan effortlessly shakes a consoling plaster from his sleeve, the rockabilly stomper “Silent Weekend”, which could just as well have been plucked from the repertoire of Ronnie Hawkins.

Levon has wandered around in his almost two-year retreat. Lying on the beach in Mexico until his money runs out, traveling with an old friend from Arkansas from job to idleness to job through Florida, Tennessee and Louisiana, until he signs at the Aquatic Engineering and Construction Company in Houma, in the heart of Bayou Country, and then some months aboard a ship laying oil pipes in the Gulf of Mexico.

On his return after the telephone call from Danko, he is pleasantly surprised to hear how Richard Manuel has picked up the drumsticks and Levon is particularly pleased with his steep learning curve and level:

“Richard was an incredible drummer. He played loosey-goosey, a little behind the beat, and it really swung. (Later, when we were playing shows, Richard would hit the high-hat so hard the cymbal would break.) Knowing Richard, I shouldn’t have been surprised at this, but I was amazed how good he’d become. Without any training, he’d do these hard left-handed moves and piano-wise licks, priceless shit – very unusual.”

… more or less forcing Levon to become more proficient in other instruments – especially his beloved mandolin.

For the time being, however, Richard graciously steps down and returns his place behind the drum kit to his former band leader, marking the actual starting point of The Band. “Silent Weekend” is one of the first recordings with Helm. And despite all the friendly words from Levon, it immediately shows that there is now a real drummer in the house.

When Dylan occasionally is away (three times) to record John Wesley Harding in Nashville, the quintet tinkers further with their unique sound that a little later will be displayed on the masterpieces Music From The Big Pink (1968) and The Band (1969). The return of Levon Helm ignites it. And, as Otou Yumi says to his wife on the bench: “There’s no going back now, I guess.”

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 590 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/568/Silent-Weekend

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.