by Jochen Markhorst

In Scotland and parts of England, the black dog represents good luck. But elsewhere one of the more persistent myths about the black dog phenomenon concerns the instinctive fear that people are said have for it.

In Scotland and parts of England, the black dog represents good luck. But elsewhere one of the more persistent myths about the black dog phenomenon concerns the instinctive fear that people are said have for it.

This is proven by animal shelter statistics: in many countries the chance that a black dog is taken by new owners is considerably smaller than with the different-coloured yapping tail-waggers. Research into this is inconclusive and therefore remains popular – for decades now there have been a number of academics every year who freshly start again tally marking in order to produce and defend with those figures usually weightless positions in theses. Especially in the anthrozoological faculties, obviously, but also the sociologists do participate diligently.

In the arts, the black dog is usually used to instill fear. Holmes’ Hound Of The Baskervilles is black (also in all 25 films since 1914), in Ian McEwan’s novel Black Dogs the Gestapo uses them as guard dogs and there they symbolize the evil what Western Civilization is capable of, the devil appears in Goethe’s Faust in the form of a black poodle, and when Breughel paints a black dog it is a bringer of bad luck and misery.

But much more poetic, and perhaps more famous, the Black Dog is known as a metaphor for depression. This interpretation is usually attributed to Churchill, who has indeed made it known by repeatedly referring to his own deep depression with the image of a black dog. “I think thist man might be useful to me,” he writes about a German psychiatrist, “if my black dog returns.”

However, the comparison is much older. As early as 1882, R.L. Stevenson (the Scottish author of Treasure Island) describes a melancholy figure as a man with “the black dog upon his back”, but Churchill probably got it from Samuel Johnson (1709-1784), from whose work Dylan sometimes draws (“Sweetheart Like You”, for example). Dr. Johnson, who, like Churchill, is a mentally unstable, literary genius, describes his “melancholy” as a black dog in various letters, suggesting that it is a common expression in the 18th century. And probably even longer; Horace knows already around 40 BC that a black dog brings bad luck and, somewhat roughly translated, will be your companion if “you hate your own company”.

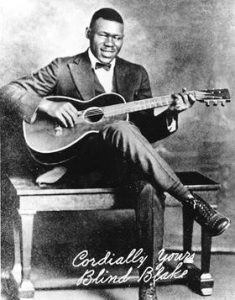

The black dog in “Obviously 5 Believers” belongs to the depression-bringing breed too. The song is initially called “Black Dog Blues”, before Dylan inserts the verse with the five believers and renames the song dadaesque, in line with titles such as “Absolutely Sweet Marie”, “4th Time Around” or “Temporary Like Achilles”. The original title the minstrel borrows from one of his old heroes, from Blind Blake, whom he will later honour more directly with a cover of his “You Gonna Quit Me Blues” (which will be the title song of Dylan’s album Good As I Been To You) .

Arthur “Blind” Blake (1896-1934) is one of the founding fathers of the blues and is in the same league as, for example, Blind Willie McTell and Charley Patton. And especially because of his phenomenal guitar playing; the integration of the ragtime piano sound is gratefully copied to this day by guitarists such as Mark Knopfler.

Arthur “Blind” Blake (1896-1934) is one of the founding fathers of the blues and is in the same league as, for example, Blind Willie McTell and Charley Patton. And especially because of his phenomenal guitar playing; the integration of the ragtime piano sound is gratefully copied to this day by guitarists such as Mark Knopfler.

Blake’s first hit “Early Morning Blues” echoes through in Dylan’s opening words, and fragments of Blake songs are then heard in every subsequent verse, except in those surrealistic fifteen jugglers / five believers stophes. Although … “Fighting The Jug” comes close. Musically Dylan is less close to Blind Blake. Even though he (presumably) lived in Chicago for several years, Blake is not from the Chicago School, where the music of “Obviously 5 Believers” is clearly rooted. Maybe by accident; Robbie Robertson tells Cameron Crowe in 1985 that the Nashville studio musicians essentially just did their job, and this particular song happens to be an example where they changed the direction:

“I remember the Nashville studio musicians playing a lot of card games. Dylan would finish a song, we would cut the song and then they’d go back to cards. They basically did their routine, and it sounded beautiful. Some songs pushed it somewhere else, like Obviously Five Believers where we had four screaming guitar solos.”

… pushing it into the direction of a sharp, driven and energetic Chicago blues, that is. Simple enough, but less simple than Dylan himself seems to think. His slightly irritated outburst during the recordings is well-known: “Hey, what the f …,” he shouts at the second, prematurely interrupted take, “this is very easy man, this is very easy to do.”

Dylan apparently does not realize that he lets the experienced Nashville cats play a traditional twelve-bar blues, but that his couplets are only ten bars long; eight bars of vocals plus two bars instrumental is quite unusual (“Good Morning Little Schoolgirl” by Muddy Waters has a similar abnormality). Granted, not quantum mechanics, but still something to pay attention to. It’s the last recording session for Blonde On Blonde, it’s already past midnight – the sharpness is no longer there, understandably. Some complaining in the background and Dylan cuts it off: “Okay, let’s try it this time, I don’t want to spend no time with this song, man.”

Not too affectionate. Dylan already illustrates this disposability during the session: in each of the four takes the lyrics change, occasionally completely off the cuff ad-libbing some random words to fill up the line. After the recording, he ignores the song, it is not performed on stage and seems soon forgotten.

Until June ’85, when Dylan is a guest at a radio show that is broadcast nationwide. One of the songs that Bob himself has requested is “Obviously 5 Believers”, and host Bob Coburn is surprised:

Coburn: You wanted us to play “Obviously Five Believers”. Why? Why do you still want us to play that song?

Dylan: I just like it.

Coburn: You just like that song; here it is.

Obviously Five Believers plays.

Coburn: Some pretty nasty blues harmonica there Bob Dylan. “Obviously Five Believers” from Blonde On Blonde.

Dylan: That’s not me though…

Coburn: That’s not you, though? Who is it?

Dylan: That’s Charlie McCoy.

But even in the years that follow, the song does not appear on the concerts’ playlists, and Dylan’s choice at the radio show seems to have been one of his smokescreens again… when the song suddenly pops up on the set list in May 1995. It is no ad hoc folly either: up until April 1997 the master performs it forty times. And he does indeed seem to enjoy it.

Despite this unexpected revival, however, the song remains a curiosity, and the same goes for the colleagues: there are not too many covers – actually only two noteworthy, both adding equally little to the original.

Top Jimmy and the Rhythm Pigs from Los Angeles release their debut album Pigus Drunkus Maximus in 1987, despite the adolescent title an infectious, exciting blues rock exercise. Striking are “Ballad Of A Thin Man” and Merle Haggard’s “Working Man Blues”, but the highlight is a steamy version of “Obviously 5 Believers”.

A bit more attractive, on more fronts, is Toni Price on her second album Hey (1995). The band is filthy and mean, no better or worse than Top Jimmy’s, but hey: the drawling, sensual vocals of the quite irresistible Texan lady really are a plus. An antidepressant, actually.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 590 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, is starting to link back to our reviews

Jesse Winchester’s “Black Dog” should have been mentioned…from his first album on Bearsville…

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/461/Obviously-Five-Believers

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.