by Jochen Markhorst

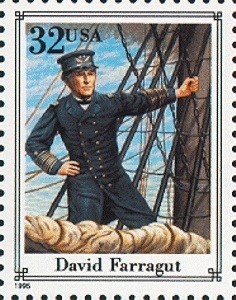

The USS Tecumseh, a monitor ship of the Northern Navy, strikes a mine and sinks within minutes. Behind it is the formidable, heavily armed three-masted sloop-of-war USS Brooklyn. Captain James Alden is warned for “a row of suspicious looking buoys” directly under the bow, stops and starts to manoeuver backwards. Lashed to the rigging of his flagship, the USS Hartford, commanding rear admiral David Farragut sees the event and he curses his ships forward again:

The USS Tecumseh, a monitor ship of the Northern Navy, strikes a mine and sinks within minutes. Behind it is the formidable, heavily armed three-masted sloop-of-war USS Brooklyn. Captain James Alden is warned for “a row of suspicious looking buoys” directly under the bow, stops and starts to manoeuver backwards. Lashed to the rigging of his flagship, the USS Hartford, commanding rear admiral David Farragut sees the event and he curses his ships forward again:

“Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead!”

Fortis Fortuna adiuvat, Fortune favours the brave; the rest of the fleet sails in one piece through the minefield, defeats the Confederates and goes ashore. The Battle in the Bay of Mobile, August 5, 1864, is decided, a few days later the city itself falls.

A hundred years later, thanks to the port, shipyards and steel, Mobile has developed into a modern, prosperous town, but it remains Southern. In the whole of the twentieth century it is mainly in the news with yet another racist incident – in February 1966, when Dylan records Memphis Blues Again, Mobile still has a backward, redneck image; you really rather be in Memphis.

The yearning for Memphis is at least as old as the blues music itself. One of the very first songs with the word blues in the title is “The Memphis Blues” by W.C. Handy from 1909, which is worded in 1912 by George A. Norton, who longs for Memphis, just because Handy plays this song:

There’s nothing like the Handy Band that played the Memphis Blues so grand.

Oh play them Blues.

That melancholy strain, that ever haunting refrain

Is like a sweet old sorrow song

Norton’s ode is perhaps the first, but certainly not the last. Chuck Berry, Muddy Waters, Jerry Lee Lewis and hundreds of other artists sing the largest city in Tennessee. The website of the Memphis Rock ‘n’ Soul Museum keeps the score: today there are more than 1000 recordings on the list.

Dylan knows all about it. Episode 31 of his Theme Time Radio Hour (November 29, 2006) is dedicated to Tennessee, more than half of the playlist is about Memphis.

Direct inspiration, however, seems to come from Sinatra, or rather: from the granite monument “Blues In The Night”.

“Blues In The Night” is somewhere in the front of The Great American Songbook. Even composer Harold Arlen, usually a modest man who can’t be caught patting his own back, gets excited again when his biographer Edward Jablonski asks about this song: “I knew it was strong, strong, strong!” (Rhythm, Rainbow And Blues, 1996 ). He even takes, very unusual, credit for a part of Johnny Mercer’s lyrics:

“It sounded marvellous once I got to the second stanza but that first twelve was weak tea. On the third or fourth page of his work sheets I saw some lines—one of them was ‘My momma done tol’ me, when I was in knee pants.’ I said, ‘Why don’t you try that?’ It was one of the very few times I’ve ever suggested anything like that to John.”

(in Alec Wilder’s American Popular Song, 1972)

Dylan is a fan of lyricist Johnny Mercer, and especially of this song, although in Chronicles he still seems to think it’s all Harold Arlen:

“Arlen had written “The Man That Got Away” and the cosmic “Somewhere Over the Rainbow”, another song by Judy Garland. He had written a lot of other popular songs, too — the powerful “Blues in the Night”, “Stormy Weather”, “Come Rain or Come Shine”, “Get Happy”, In Harold’s songs, I could hear rural blues and folk music. There was an emotional kinship there.”

Of course; Woody Guthrie, Hank Williams, Hank Snow… they are all deeper under his skin, “but I could never escape from the bittersweet, lonely, intense world of Harold Arlen.”

Copywriter Johnny Mercer does not get explicit credits from the bard, but indirectly more than once. From this song, from “Blues In The Night”, the Dylan fan recognizes

Now the rain’s a-fallin’

Hear the train a-callin

… of which echoes descend in “A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall” and in “Dusty Old Fairgrounds”, and the chorus

The evenin’ breeze’ll start the trees to cryin’

And the moon’ll hide it’s light

When you get the blues in the night

Take my word, the mockingbird’ll sing the saddest kind of song

He knows things are wrong, and he’s right

… reveals where Dylan borrowed that atypical combination of moon and mockingbird from “I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight” (and that last line comes very close to “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome”, first verse – when something’s not right, it’s wrong). and the fourth verse opens with

From Natchez to Mobile

From Memphis to St. Joe

…which should sound familiar too.

With some cut and paste work, in short, the classic “Blues In The Night” can be reconstructed in its entirety from Dylan’s Collected Works.

The refrain of “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again” is therefore a not too complex, yet fresh version of an old romantic cliché: it expresses the classic Sehnsucht, the desire for an unattainable ideal. Dylan then enriches this with a sharp edge, by securing the languid I-person like a Tantalos, at a distance of about 380 mile from that heavenly Memphis.

The couplets are not so unambiguous. Here sparkles the psychedelic Dylan, the wordsmith of “Desolation Row” and “Tombstone Blues”, who gazes through his sciopticon and twirls the impressions with a magic pen on his hotel stationary. Thus, the poet grants us nine completely unrelated, impressionistic fragments from a colourful life. Some of them are traceable, perhaps.

The bloodthirsty railway staff from the third verse lends Dylan from the old folksong “I Wish I Was A Mole In The Ground”:

The bloodthirsty railway staff from the third verse lends Dylan from the old folksong “I Wish I Was A Mole In The Ground”:

No, I don’t like a railroad man.

‘Cause a railroad man, they’ll kill you when he can,

And drink up your blood like wine.

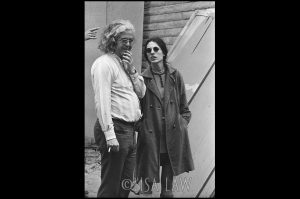

And to author Peter Coyote we owe the observation that sheds light on the following enigmatic rules (An’ he just smoked my eyelids / An’ punched my cigarette): Dylan’s manager Albert Grossman has a rather peculiar way of holding his cigarette – the hand clenched into a fist, the cigarette wedged between the little finger and ring finger:

“Albert was droning on with a cigarette jutting out of his fist, oblivious to the Rosetta stone accuracy of Dylan’s observations on the speakers behind him. I was transfixed by the literalness and specificity of the images. I felt like I was hearing a headline, and decided at that moment, that for all his surrealistic affectations, Dylan was a very literal chronicler of an absurd world. It was not his lyrics, but his subject matter which was bizarre, and much could be learned by paying attention.”

Like this, every couplet opens the gate for grateful Dylan exegetes, with that parade of obscure, eccentric passers-by (neon madmen and a dismayed priest), exotic decors (a honky-tonk lagoon under the Panamanian moon) and weird props (railroad gin and a stolen post office). And, as usual in these days, all the stops are being pulled out.

Quite tiresome then are the attempts to deduce an epic, coherent story from the poetic fragments. The decline of a patient in a rehab clinic, a journey through the Purgatory of a soul looking for Paradise, something with Vietnam … especially on expectingrain.com, there is a lot of despair. The puzzlers who search for their crypto-analysis in the lyrical corner are more tolerable. The interpretations that assume Dylan captures in words the impression his tumultuous life now makes on him, do cut some ice. A lot of images and descriptions can be traced back to associative word play, to the catachreses that Dylan loves so much in this phase of his artistry.

The meaningless, but quite melodic sounding honky-tonk lagoon is a deliberate abusio, a “misuse” of the term honky-tonk saloon, for example. Neon madmen seems to be a traceable impression of the advertising boys on Madison Avenue, who, incidentally, despite what the successful television series suggests, were not called Mad Men at all. But Dylan’s Chelsea Hotel is a five minutes walk from Madison Avenue with its admen. In 1965, a language-sensitive word artist like Dylan effortlessly plucks that word play from the air.

In any case, it is irrelevant to the enjoyment of Dylan’s art, to know what Dylan “actually” tells, which images would be meant as a metaphor for which biographical fact and who would hide behind the ragman or the senator. Moreover; many of the code crackers trivialise the poetry – unintentionally, we may assume – with their attempts to clarify; but after all, a jewel shines more beautifully in the semi-darkness than in full daylight.

And a jewel it is. For those same fans on expectingrain it often is a favourite song and also with professionals like Sean Wilentz, Frank Black (from The Pixies) and Michael Gray, the song ranks high. Even organist Al Kooper, who usually looks back rather objectively, with witty self-mockery and irony, at his contributions, is still enthusiastic: “I heard it again recently and went, Wow! Usually I go Oww!”. After which he, very gentlemanlike, gives the most credits to guitarist Joe South.

The poetic mosaic indeed is beautifully packaged. The final version on Blonde On Blonde is, thanks to that irresistible thin wild mercury sound, unbeatable. The official release of the rejected versions (The Cutting Edge, 2015) only confirms that the chemistry of Dylan and the Nashville cats is building a rock-historic Mount Everest in the spring of ’66; higher is not possible. The attempt by Cat Power for the I’m Not There soundtrack (2007) is quite fun, the version of the North Mississippi Allstars (on Uncut’s tribute Happy Birthday Bob, 2011) is beautiful and the Spanish flamenco by Kiko Veneno (1995) charming and exciting, but still – they remain well below that summit, all of them.

Well alright, the Old Crow Medicine Show is, as usual, pretty irresistible with their bluegrassy, cajun Tex-Mex, cowpunky, damn-the-torpedoes approach on 50 Years of Blonde on Blonde (2016).

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 592 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/601/Stuck-Inside-of-Mobile-with-the-Memphis-Blues-Again

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.