by Jochen Markhorst

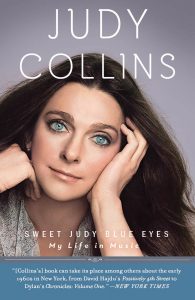

In her rather complacent autobiography Sweet Judy Blue Eyes (2012), Judy Collins remembers an imminent cat-fight with Joan Baez which is lulled by lawyers. Baez has heard that Collins wants to record “I’ll Keep It With Mine” for her Fifth Album, but claims that Bob has written that song for her. Generously, Collins writes:

In her rather complacent autobiography Sweet Judy Blue Eyes (2012), Judy Collins remembers an imminent cat-fight with Joan Baez which is lulled by lawyers. Baez has heard that Collins wants to record “I’ll Keep It With Mine” for her Fifth Album, but claims that Bob has written that song for her. Generously, Collins writes:

“I think Bob had just forgotten whom he wrote it for, or perhaps he wanted to make Joanie mad. They had been an on-again, off-again thing for a while. I won, if you want to call it that, but I always wondered if, in fact, he had told me the truth.”

Bob had simply forgotten who he had written it for. But a paragraph later she triumphs nonetheless:

“Years later, when I was recording an all-Dylan album, I found that Bob had written extensive liner notes, in which he clearly acknowledged writing “I’ll Keep It with Mine” for me. I was, of course, honoured. Who wouldn’t be?”

Well. Never trust blue eyes.

The liner notes in question were not written by Dylan, but by Cameron Crowe. And it is certainly not “clearly acknowledged” that he wrote it for her, but that this rare tape was recorded for Judy Collins … and recording a song for a pretty girl is of course not the same as writing a song for her.

Anyhow: the first real release of “I’ll Keep It With Mine” is indeed in her name – a fairly attractive single from 1965, on which she is assisted by, among others, Al Kooper on organ and Mike Bloomfield on guitar. Critic Robert Shelton is not the only one who is impressed (“one of the best folk-rock performances yet recorded,” as he writes in The New York Times), but nevertheless the single flops and Judy discards the recording for her Fifth Album.

In 2001, the flop still bothers her a bit, apparently. Journalist Richie Unterberger writes the Liner Notes For Elektra Non-LP Rarities and quotes from an interview with Judy Collins:

“There’s a very good reason that it never made it onto an album,” Collins told me in 2001. “It’s not a very good song, particularly. Certainly not a Dylan song that lives up to its name. It doesn’t really go anywhere, the lyric’s kind of flat, and the singing is very flat.”

With which she, not very elegantly, blames Dylan for the flop. And just to be sure, she claims her right once again, misquoting Biograph once again:

“All the same, I love the idea that he said, at least said to me, that he wrote the song for me. Then he told Joanie Baez that he wrote it for her. There was some talk about that, as to who did what. Of course, he says in his retrospective album [Biograph] that he wrote the song for me.”

In addition to Mrs. Collins and Joan Baez, there is a third party, a third lady who is also claiming: the originally German Christa Päffchen (1938-1988), better known as Nico. The nature of her relationship with Dylan is somewhat diffuse. With some biographers, the story pops up that she spent a few weeks with Dylan, travelling from Paris to a town near Athens, the coastal village of “Vernilya” (according to Clinton Heylin) or “Vermilya” (according to Robert Shelton). That place does not exist in either of the two spellings.

More reliable is the bequeathed testimony of Dylan’s handyman Victor Maimudes, who tells he drove Dylan for a short sunny holiday to Vouliagmeni, a coastal town that is indeed 23 kilometres below Athens. After his death, Victor Maymudes left a whole stack of recorded cassettes, which his son Jacob processed into the book Another Side Of Bob Dylan (2014).

The trip to Greece is described fairly extensively, two pages (685 words), but Nico is not mentioned. “Two elderly ladies” are. They run a little hotel, take lovingly care of Bob “day and night” and do not speak a single word of English, which makes the stay a “charming experience”.

The source of the story that Miss Päffchen accompanies Dylan there is Nico herself, who famously has a strong tendency to mythologize and most certainly did not choke on her first lie. It is recorded by Richard Witts in his biography Nico: Life And Lies Of An Icon (1993), in which Nico greatly enhances the romantic interlude in Paris with witty observations and highly questionable statements:

“Nico didn’t understand a word of his music. “Twing, twang, twing, twang, baybee: that’s how it went.

(…)

As I was from Berlin, he asked me if I knew the playwright Brecht. I told him that Brecht had a theatre in Berlin, but we were forbidden to go there because it was in the Soviet sector. He said: “You see? That would never happen in America. At least we are free to see things.” I said, “But it’s the Americans who are stopping us walking through.” For a man who was preaching about politics, he did not know his history too well.

(…)

So, then we went together to Greece for a short time, a little place near Athens, and he wrote me a song about me and my little baby. (…) The song is titled “I’ll Keep It With Mine”.”

So, casually, she reveals that “I’ll Keep It With Mine” is about her and her son, and was given to her on the spot.

She then records the song for her debut Chelsea Girl (1967), after trying to get it on the Velvet Underground setlist earlier. On a curious bootleg, All Tomorrow’s Parties, a raw version from February 1966 can be heard – only accompanied by Lou Reed, who in fact puts the slashy, aggressive part of “I’m Waiting For The Man” under the song.

Dylan himself has trouble with the song. After the Witmark demo in June ’64, he makes two attempts at the Bringing It All Back Home sessions and eleven attempts at the Blonde On Blonde sessions in Nashville, but he can’t get it done (as Dylan seems to think; the instrumental takes, recorded without Dylan, are truly thin wild mercury beauties). The true conviction also seems to be lacking, considering his implicit rejection in the Biograph booklet:

“A lot of stuff I’ve left off of my records I just haven’t felt as been good enough. Or maybe it didn’t sound like a record to me. I never even recorded I’ll Keep It With Mine, you know… but if people like it, they like it.”

And he never performs it live either. On the other hand: those many, many studio attempts suggest that Dylan does at least suspect the song’s strength – and gets frustrated because he is unable to unleash this suspected power.

The fact that Dylan keeps returning to this song for more almost two years is probably due to the lyrics’ appeal. Crystal clear, but impenetrable. No extravagancies like guilty funeral directors, bloodthirsty train staff or Persian drunks, no wideranging excesses, but short sentences, simple words with few syllables and a sober cast: a “you” and a “me”. The two lines of verse that stand out (how long can you search for what’s not lost and I’m not loving you for what you are, but for what you’re not) are clear too.

And yet it is completely mysterious; the title alone cannot be clearly understood – what does he keep with him? “Time”? He seems unintentionally concealing, the narrator, who is a remarkably sensitive, probably older and at least a fatherly wise narrator, and who allows himself to be vulnerable – a rare appearance among the often sneering, hurting and condescending protagonists in Dylan’s love lyricism in these years. But we don’t get more than a vague representation of the things around it. The first two verses outline a comforting, loving and understanding lover, and by introducing the scenery, a platform, in the last verse, we might be tempted to think: a dramatic farewell scene – but no, he will be back tomorrow. Or will he? A weary conductor suddenly appears, trapped in the back and forth of the railway line, he will take the narrator with him. Like a ferryman of Death.

Enigmatic. And beautiful.

Like many of Dylan’s lost classics, this song is not orphaned. After Collins and Nico, dozens of artists eagerly take a shot a “I’ll Keep It With Mine”.

Fairport Convention is the first to recognize, in 1969, the slightly lurid undertone of the work and plays a brilliant version on the album What We Did On Our Holidays. The band of Richard Thompson and Sandy Denny remains committed to the song well into the 21st century.

In 2010, Dean and Britta deliver the music for thirteen Andy Warhol movies from the 1960s, and then choose the Dylan song for Nico’s screen test – and improve the light-hearted version of Nico from 1967.

And then there are the compelling version by Marianne Faithfull (on the wonderful Strange Weather, 1987), a quirky and supercooled rendition by Oh Susanna (2003), the violins of Bangle Susanna Hoffs (with Rainy Day, 1984) and the atmospheric, hollow lecture by the emo trio from Wisconsin, Rainer Maria (on Catastrophe Keeps Us Together, 2006); again it’s the ladies who score the most moving and respectful Dylan covers.

And it is also a lady to whom we can thank the perhaps most beautiful “I’ll Keep It With Mine” of the past 50 years: frontwoman Carol van Dijk from the Dutch band Bettie Serveert. Their contribution to the soundtrack I Shot Andy Warhol (1996) is both Horn of Plenty and Pandora’s Box at the same time – initially an intimately produced up-tempo pop ballad, energetically suppressed, with surprising, short contributions from the village fanfare in the first two couplets and later derailing with a wild, detonating Velvet Underground-like eruption after the last verse.

Dylan did write the song for Carol van Dijk. Case closed.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 594 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews

It’s a beautiful song, very powerful. The version I love most is the Bank Account Blues version on piano, a solid, confident song with a hollering hook line. It doesn’t really sound like other stuff he was doing around 1964, so maybe he felt a little wary of it. It’s not the first time Bob judged his songs differently though, is it?

Beautiful article too, Jochen. Fascinating tale. I doubt Judy Collins ever read the liner notes to Biograph, or if she did, her ego swelled up on reading her name and she’s confused about who it was who mentioned her…

A terrific exploration of a song that has intrigued me since I first heard it on Biograph. Truly one of your best. And thank you for the introduction to Bettie Serveert.

I too have always loved the line: “I’m not loving you for what you are, but for what you’re not.” I use know this very attractive woman who was so down to earth and modest and I often thought of this line around her. She easily could have been conceited but she was not.

That’s a lovely thought JZ

Thanks for you thoughts on this song.

Apart from the Widmark demo, which might be as good as any except it seems to derive from a damaged acetate, there is another early recoring of I’ll Keep It With Mine. This appears towards the end of the DLB bonus video 1965 Revisited. The sccene features Dylan in conversation with Nico and the editing implies that he serenades her with this song. Sadly we do not get the whole song so perhaps it is incomplete anyway.

I’ll Keep It With Mine is a teasingly elusive song. Bank Account Blues suggests that saving time is somehow like saving money. But the words are deceptive, especially ‘save you’ and ‘any time’. Either he promises to help her not waste time by spending it with him; or he promises to rescue and guard her safely, or even redeem her. Similarlyv ‘any time’ operates quite differently when you hear it as an adverb ‘anytime’ – spend some time with me becomes I can save your soul whenever you are ready.

In the studio Dylan does not record the song on the piano entirely unaccompanied: a metronome marks the beat – the perfect way to ‘keep time’!

The place in Greece where Dylan stayed in 64 is Vouliagmeni, as revealed in Victor Maymudes’ book

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Another_Side_of_Bob_Dylan

1965 interview with Nico about meeting Dylan in 1964 in Paris

http://velvetforum.com/viewtopic.php?t=145779

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/298/Ill-Keep-It-with-Mine

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.