by Jochen Markhorst

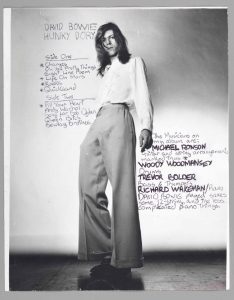

Among the many pearls glittering on one of his most beautiful albums, Hunky Dory from 1971, shines the remarkable “Song For Bob Dylan”, a beautiful song with a striking text, of which the often quoted a voice like sand and glue are the most memorable words.

Among the many pearls glittering on one of his most beautiful albums, Hunky Dory from 1971, shines the remarkable “Song For Bob Dylan”, a beautiful song with a striking text, of which the often quoted a voice like sand and glue are the most memorable words.

Bowie’s song doesn’t fall from the sky. With the partly idolating, partly reproaching ode, the British chameleon shakes off the Dylan feathers he has worn for a year or two: on his playlist are the Dylan covers “She Belongs To Me” and “Don’t Think Twice”, for a while he performs in a Dylan-1963 look, including proletarian cap, the first two albums are filled with half and full Dylan references and the word dylanesque is a constant in the (mostly positive) reviews of those LPs. In an interview for Melody Maker (’76) the singer looks back on “Song For Bob Dylan”:

“It was at that period that I said,OK, if you don’t want to do it, I will. I saw the leadership void.”

But he remains faithful to his idol in the following decades. In this same Hunky Dory period Bowie records another unreleased nod to Dylan, “It’s Gonna Rain Again”, with the hobby project Tin Machine he releases “Maggie’s Farm” on a single, in between with the band of Bryan Adams he records a heavy but attractive “Like A Rolling Stone” and most of all: in 1998 he takes a shot at “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven”. Never officially released, unfortunately, although it is a mesmerizing version.

It is a very well-chosen cover. With its despondent, dark verses full of mysterious imagery and expressive metaphors, the monumental masterpiece is situated exactly at the intersection of Dylan’s and Bowie’s repertoire – even the title fits both Bowie’s first hit “Space Oddity” (1969) and his last, “Lazarus” (2016).

In reviews, the song is often mentioned in the same breath as that other monument on Time Out Of Mind, “Not Dark Yet”. Understandable: apart from the music both songs are also thematically comparable. The narrator despairs, the end of life approaches inevitably.

Tryin’ is still slightly less desolate. Where “Not Dark Yet” does not even offer the prospect of redemption in an afterlife (“I just don’t see why I should take care”), at least the gate to heaven is open here – still, anyway. Though it is far from a consoling, cloudless counterpart of “Not Dark Yet”, obviously. Predominant is an identical worn-out languor, embedded in the same structure: both lyrics are cast in Dylan’s beloved François Villon format, songs without a chorus but with recurring refrain lines that end every verse.

Tryin’ is more accessible. Dylan opts for the well-known, almost archaic life path metaphor, as it has been worded for centuries, by poets such as Emiliy Dickinson, Pablo Neruda, Paul McCartney and Robert Frost:

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth

(The Road Not Taken, 1916)

In every couplet the narrator travels, the protagonist is literally on his way and in a figurative sense tries to reach the gate of heaven. The I-person roams from the middle of nowhere to Missouri, follows the Mississippi up to the estuary, as far as New Orleans and thus roughly follows Highway 61. On the way, he plucks to his heart’s content from the blues idiom. “Trying To Get To Heaven” Dylan already hears in 1962, at a concert by Reverend Gary Davis in Gerde’s Folk City, and he is probably familiar with Al Koopers variant, with the chorus “Tryin’ to get to heaven in due time / Before the heaven doors close” (“Wake Me Shake Me”, The Blues Project, 1966).

Just as classic and extremely effective is the trick with which the poet sets the mood in the first two lines: the threatening, dampening silence preceding a summer thunderstorm.

As in many of Dylan’s most beautiful works, the lyrics reach lyrical and poetic peaks through this combination: the connection of fragments of blues clichés (“wading through the high muddy water”) with paraphrase (the Biblical lonesome valley comes from Psalm 23) and catachresis, innovative word combinations (“The heat rising in my eyes”). “You can seal up the book and not write anymore” is another great find, such an elegant variant of the Closed Book as a metaphor for the end of a relationship.

Teasing are the nostalgic references to drug consumption. Mary-Jane is an almost antique pseudonym for marijuana, but Dylan’s first association is the whore madam from the old folk song “Ridin ‘In A Buggy, Miss Mary Jane”, which he probably knows in the performance of Pete’s half-sister Peggy Seeger (1958) :

Oh, Miss Mary Jane. Sally's got a house in Baltimore, in Baltimore, in Baltimore. Sally's got a house in Baltimore, and it's full of chicken pie.

Thanks to Nancy Sinatra’s “Sugar Town” (1966) and especially the frank explanation by songwriter Lee Hazlewood, we know that Sugar Town is sugar cubes drenched in LSD. In a few reviews of Tryin’, it is partly therefore concluded that the entire song is a tribute to the deceased Jerry Garcia – and also because it is possible, with some kung-fu acrobatics, to filter fragments of Grateful Dead song titles from the song. It is a hardly sustainable thesis with thin evidence. And anyway: whenever Dylan writes an admiring in memoriam, he is far from vague or ambiguous: “Lenny Bruce”, “Roll On John”, “Blind Willie McTell”, “High Water (For Charley Patton)”.

Sugar Town – Nancy Sinatra (not the best qualty, but a wonderful, corny videoclip):

The literary peak is in the middle, as it should be. The third verse portrays in a masterful, stifling way the meaninglessness of existence, by observing a platform full of commuters: “I can hear their hearts a-beatin’ / Like pendulums swinging on chains.”

The following lines are different from the published lyrics on bobdylan.com. The official site states:

I tried to give you everything That your heart was longing for

Already in the studio Dylan stumbles over its too clichéd nature and improves it to the much more powerful, much more desperate

When you think that you’ve lost everything, You find out you can always lose a little more.

Lucinda Willams’ cover (on the Amnesty project Chimes Of Freedom, 2012) is appreciated, in general. Overappreciated. It is true that the instrumentation is beautiful, but Williams’ singing is terrible, overacting like a Nicholas Cage in a ten a penny action movie (with a similar dictation too, by the way) and Lucinda is so busy groaning and gasping that it becomes painfully clear: she has no idea what she is singing.

Then the reading by veteran Peter Rowan, a bluegrass musician from a lower division, is much more attractive. With the Czech backing band Drúha Tráva, he records a dreamy, sultry version for the album New Freedom Bell in 1999. And the interpretation by loyal Dylan disciple Robyn Hitchcock, with the cooperation of recognized Dylan interpreters Gillian Welch and David Rawlings, is very attractive too (on Spooked, 2004).

But towering far above them all is the gothic cathedral Bowie constructs from “Tryin’ To Get To Heaven”. Bowie’s respect is almost tangible, but it doesn’t paralyze him. An artist of his calibre dares to deviate from the original, an artist with his qualities knows how to enrich the original. Bowie’s tendency to the theatrical is of course much more pronounced than Dylan’s tendency to dramatize, fitting this work very well. Unlike in the parent song, a sharply rising tension curve is constructed here, which, very dramatically, collapses halfway. The intensity with which Bowie then sings the last two verses is chilling.

It is a magnificent cover by a great artist.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 594 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews

FYI, the “elegant” turn of phrase, “You can seal up the book and not write anymore,” is a not so transparent allusion to both the Old Testament Hebrew prophet Daniel, instructed by the Archangel Michael to,

… shut up the words [of the prophecy] and seal the book until the time of the end…”

Daniel 12:4

https://biblehub.com/daniel/12-4.htm

This language is repeated in the New Testament book of Revelation, in chapter 10:4

“Now when the seven thunders uttered their voices, I was about to write; but I heard a voice from heaven saying to me, “Seal up the things which the seven thunders uttered, and do not write them.””

https://biblehub.com/revelation/10-4.htm

Perhaps there is a bit more meaning than the “meaninglessness of life” in the lyrics.

Just one more observation: when you go to new Orleans on the Mississippi River, you go down, not up to it. NOLA, being on the Delta, is at or below sea level.

Bill, in Kansas City

(12th Street & Vine)

I wish I shared your high opinion of Bowie’s cover. To me it sounds like he’s lost the song–or never found it–and is trying to cover with acting. It’s nice to know that he admired the song, at least.

I doubt Dylan’s Sugar Town has anything to do with Nancy Sinatra’s. Of course he would have known that song, but his lyric comes straight from an African American folk song, “Buck-Eye Rabbit”:

I wanted sugah very much,

I went to Sugah Town

I climbed up in that sugah tree.

An’ I shook that sugah down.

(I take this from Eyolf Østrem’s discussion of the song on his Dylanchords site; Eyolf quotes a post on the r.m.d. site.)

“I’ve been walking that lonesome valley” doesn’t come from the 23rd Psalm, at least not directly. It comes from the old gospel song: “You’ve got to walk that lonesome valley / You’ve got to walk it by yourself.” Which is of course just what the singer in Dylan’s song is doing. As with so many of Dylan’s songs, one has to be careful about assuming that biblical allusions come straight from the Bible. He knows his Bible, of course, but he also knows the world of folk and blues and gospel songs that draw on it. Before he got religion, they were his Bible.

“I tried to give you everything / That your heart was longing for” is not from a rough draft. It’s what he actually sang in concert, years after first recording the song. And it doesn’t replace the “When you think that you’ve lost everything” lines; those are moved to the last verse, replacing the “Some trains don’t carry no gamblers” lines. It does seem a shame to lose those lines, but the revision is more than just a cliché. It’s from “The Streets of Baltimore,” written by Tompall Glaser and Harlan Howard and best known in the recordings by Bobby Bare and by Gram Parsons and Emmylou Harris: “A man feels proud to give his woman what she’s longing for / And I kind of liked the streets of Baltimore.” Perhaps Dylan is simply giving a nod to that song, prompted by the mention of Baltimore in his own song. But I suspect it was on his mind when he wrote “Trying to Get to Heaven.” Perhaps it even provided the pattern he followed. Both songs are made up of four-line stanzas (though Dylan’s lines are split into two on the page, making eight), ending with a refrain–what you call the “François Villon format.” And the refrains–“the streets of Baltimore / Trying to get to heaven before they close the door”–rhyme with each other. You could even see Dylan’s song as a kind of sequel: after the singer left his woman walking the streets of Baltimore, he never did make it back to Tennessee. He’s been wandering the world ever since, trying to get to heaven before they close the door. But that’s going a little far.

Thanks Morten and Bill,

Wonderful, enriching additions/corrections!

(And no worries, Morten; I, too, am pretty sure that Nancy Sinatra’s “Sugar Town” has no connection with Dylan’s Sugar Town whatsoever – I only seized the opportunity to insert a corny video clip of Nancy Sinatra in a minidress – which in itself is a laudable goal under any pretext, I guess).

Thanks and groeten uit Utrecht,

Jochen

Dylan’s remarkable skill in enabling his words mean different things to different people is evident here with the historic ‘ People on the platforms waiting for the trains

I can hear their hearts a-beating

Like pendulums swinging on chains

When you think that you’ve lost everything

You find out you can always loose a little more…’

which addresses his people’s recent history. The words, however, need Dylan’s compelling and sensitive vocal performance together with the compassionate music, including the soaring harmonica solo, to register there power. Dylan performed the song in Europe including Paris and, from memory, Amsterdam, soon after the song’s release.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/694/Tryin-To-Get-To-Heaven

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box.

Too many light years from home, Bowie deadens Dylan’s “Trying to Get to Heaven” by leaving most of its earth-bound lyrics behind