by Jochen Markhorst

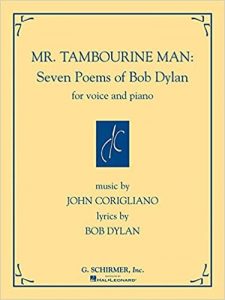

The American John Corigliano is quite a Grammy Award collector. The counter now stands at six, and in between the classical composer also scores an Oscar (for the music to The Red Violin, 1999) and the Pulitzer Prize for Music, for his Second Symphony (2001). A striking title in the list of prize-winning works has the work for which Corigliano wins his third and fourth Grammy: Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan.

The American John Corigliano is quite a Grammy Award collector. The counter now stands at six, and in between the classical composer also scores an Oscar (for the music to The Red Violin, 1999) and the Pulitzer Prize for Music, for his Second Symphony (2001). A striking title in the list of prize-winning works has the work for which Corigliano wins his third and fourth Grammy: Tambourine Man: Seven Poems of Bob Dylan.

In the program booklet at the premiere (Carnegie Hall, March 2000), Corigliano writes that he has selected the seven lyrics for their poetic value from a collection of Dylan lyrics, while he “had never heard his songs”, sketching a self-portrait of a possessed composer who works and works while life outside passes by:

“I had always heard, by reputation, of the high regard accorded the folk-ballad singer/songwriter Bob Dylan. But I was so engaged in developing my orchestral technique during the years when Dylan was heard by the rest of the world that I had never heard his songs.

So I bought a collection of his texts, and found many of them to be every bit as beautiful and as immediate as I had heard – and surprisingly well-suited to my own musical language. I then contacted Jeff Rosen, his manager, who approached Bob Dylan with the idea of re-setting his poetry to my music.”

That seems a bit too posed. Born in 1938 in New York, the city where he has lived and worked all his life… Corigliano must have had a compulsive urge to put his fingers in his ears crossing the streets, through the subway stations and parks, cafes and cinemas, through life at all, for more than forty years, to “never hear his songs”. And “coincidentally”, six of the seven lyrics he chooses from hundreds and hundreds of Dylan lyrics happen to be part of the canon: the cycle opens with “Mr. Tambourine Man”, on the way his “Blowin ‘In The Wind” and “All Along The Watchtower” are processed and the final is “Forever Young”.

The song cycle describes, according to the composer,

“… a journey of emotional and civic maturation, from the innocence of Clothes Line through the beginnings of awareness of a wider world (Blowin’ in the Wind), through the political fury of Masters of War, to a premonition of an apocalyptic future (All Along the Watchtower), culminating in a vision of a victory of ideas (Chimes of Freedom). Musically, each of the five songs introduces an accompanimental motive that becomes the principal motive of the next.”

The only title really standing out is number two, the obscure “Clothes Line Saga” from The Basement Tapes, which according to Corigliano expresses “innocence”.

Now, that is an original perspective indeed, which does show that the maestro is not hindered by any Dylan knowledge. The song, originally called “Answer To Ode”, is a pastiche. When Dylan in the basement of The Big Pink in Woodstock dashes off songs with his buddies, that summer of ’67, Bobbie Gentry’s moving country pop jewel “Ode To Billie Joe” is at the top of the charts. Dylan, who usually only parodies music he admires, imitates the emotionless recitation, the petty dialogues and the muggy boredom of the hit, but refrains from an underlying drama which makes Gentry’s ballad so blood-curdling, which provides the true power to this “study of unconscious cruelty,” as Gentry calls it.

What remains is a pointless anecdote, an overexposed snapshot of a saltless existence in a dead village, where the question of whether the laundry is already dry is more important than the news that the vice president has gone mad. It works irresistibly comically, especially because the waiting for a punch line is not being rewarded – and roughly like in dialogues at Chekhov or like Peter Sellers at his deadpan best, the comic power lies in Dylan’s lingering, monotonous recital.

For many clarifiers that is too thin. They then insist on exposing expressiveness beneath the surface. A Greil Marcus (Invisible Republic, 1997) can “crack the code of the talk”, knows we are hearing “what Raymond Chandler descibed as the American voice: flat, toneless and tiresome”, “a voice that can say almost anything while seeming to say almost nothing.” Marcus, incidentally, seems to know that the narrator is a boy, a teenage boy double for Bobbie Gentry’s teenage girl, but does not reveal from what he derives that knowledge. Obvious it is not; in the kind of household that emerges from Dylan’s thin sketch, picking up the laundry is more a woman’s job, a job entrusted to the daughter of the house, and the silly talk that the neighbour in the third verse starts with the storyteller is hardly the kind of conversation an adult man will have with his fifteen, sixteen-year-old neighbour’s son, but rather with a teenage girl.

This part of Marcus’ analysis, however, this unmotivated gender determination, does not trigger the most eyebrow-raising. That would be provoked by his thoughts on the second verse, the verse recalling how the Vice-President has gone mad. Slightly hysterical is Marcus’ insistence on his argument that this verse hides sharp political criticism of Vice President Hubert Humphrey. In the acted lethargy of the performance, he now hears that the village is actually Washington DC 1967, Humphrey is vice president, Marcus even hears criticism of Humphrey’s turnaround on civil rights since his days as mayor of Minneapolis, in 1948, and concludes that this answer song answers the question Bobbie Gentry’s hit evokes: what did the girl and the suicidal Billy Joe throw off that Tallahatchie Bridge?

Dylan’s song, Greil Marcus concludes, tells us it was the vice-president who jumped off the bridge.

Mike Marqusee (Wicked Messenger, 2006) sees in the song “a bleak social vision”, “unperturbed American complacency” and an America “cultivating amnesia”, and Oliver Trager (Keys To The Rain, 2004) even a “veiled commentary at the US resumption of attacks on North Vietnam.”

Both gentlemen acknowledge “Ode To Billie Joe” as a source, both admire the subtle way in which that song manages to move, but both also cloak themselves in the conviction that this one sentence, the Vice-President’s gone mad, is a serious, politically motivated comment, reflecting Dylan’s opinion on a current topic.

Well. Granted: fascinating or at the very least amusing struggles of well-read, eloquent gentlemen with a gem that Dylan himself never looks back on, but nevertheless very far-fetched interpretations of a text that is foremost meaningless and, precisely for that reason, funny.

The only noteworthy cover of this song is an interpretation that at the very least matches the original (switching off the dramatic Nobody-Sings-Dylan-Like-Dylan mode: it really does surpass the original).

Suzzy and Maggie Roche from The Roches are the dream candidates for an attempt: unique, unusual harmonies and very deadpan, witty presentation are characteristics of their artistry. They succeed completely; their contribution to the tribute album A Nod To Bob (2001) is quite brilliant. The ladies deliver the paradoxical juggling act to sing both toneless and melodic. The indispensable organ work of Garth Hudson turns out to be dispensable after all: the Roches arrange traditionally, but oh so effectively by trickling in more instruments per couplet. The organ is only used percussively in the second verse, but still honours Hudson in the third verse with short strokes. The coda is ingenious; after a Trugschluß, the deceptive cadence, the sisters conclude the song with a short, wordless finale that manages to even enhance the comic effect.

It is three minutes and fifteen seconds of total perfection – Suzzy and Maggie produce one of the most beautiful Dylan covers ever. Quite an achievement. Worth at least six Grammy Awards.

What else is on the site

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 595 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 2000 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, please do drop me a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article. Email Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, links back to our reviews

Thank you for posting this. It is very very long ago I heard Bobbie Gentry’s “Ode To Billie Joe”. I didn´t know lyrics then. Clothes Line Saga I never heard. Excellent song and video! Just when both songs are together here it is interesting. I think about unconscious cruelty…

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/121/Clothes-Line-Saga

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.