by Jochen Markhorst

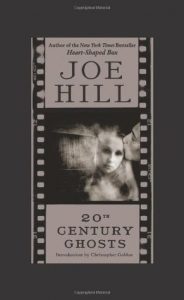

The American writer Joe Hill has been successful for a while, not only as an author of popular comics (the Locke & Key series, for example), but also as a writer of horror, thriller and fantasy since 1997. Winning him prizes, scoring hefty sales figures; some of his work has already been adapted for film too.

The American writer Joe Hill has been successful for a while, not only as an author of popular comics (the Locke & Key series, for example), but also as a writer of horror, thriller and fantasy since 1997. Winning him prizes, scoring hefty sales figures; some of his work has already been adapted for film too.

His pseudonym is unveiled in 2005 and appears to be not that made up; born in 1972 as Joseph Hillstrom King, he chooses a pseudonym because his father is the world-famous bestselling author Stephen King. Understandably, the young King would like to be judged on his own merits.

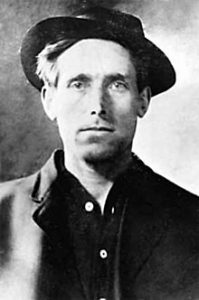

And from that first name “Joseph Hillstrom” it is only a small, historically correct step to “Joe Hill”. Father Stephen and mother Tabitha (also a talented writer) are admirers of the legendary Swedish-American union activist and honour him by naming their first son after him.

That Swede is born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund (1879-1915) and emigrates from Stockholm to the United States in 1902. He changes his name to Joseph Hillström, earns a living as a worker crisscrossing the country, in the meantime writing and drawing socially-motivated cartoons, political songs and satirical poems.

That Swede is born Joel Emmanuel Hägglund (1879-1915) and emigrates from Stockholm to the United States in 1902. He changes his name to Joseph Hillström, earns a living as a worker crisscrossing the country, in the meantime writing and drawing socially-motivated cartoons, political songs and satirical poems.

He is a tough, articulate and intelligent socialist. The latter probably plays a part in his highly dubious death sentence and subsequent execution, November 19, 1915, for the murder of a grocer and his son in Salt Lake City, Utah. On the night of the murder, Joseph Hillström, aka Joe Hill, reports to a local doctor with a gunshot wound in his hand that he refuses to explain – which is about the only incriminating fact on which he is convicted.

Years later, it turns out that Hill’s hand had been wounded in a fight over a woman, Hilda Erickson, who in a retrieved letter also recounts that Joe was shot by her ex-fiancé.

Hill’s handwritten last will is a poem that once again demonstrates his talent for pointed sketches in a firm, witty style. It opens with:

My will is easy to decide

For there is nothing to divide

My kin don’t need to fuss and moan

“Moss does not cling to rolling stone”

The entire poem is set to music decades later by Ethel Raim, who sometimes with her Pennywhistlers shares the stage with Dylan. Immortal, however, is the tragic, gifted Joe Hill mainly from “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night”, the song Earl Robinson made of Alfred Hayes’ poem in 1936. Pete Seeger sings it, Bruce Springsteen plays the song live, very Dylanesque with acoustic guitar and harmonica (2014), but the most famous version is by Joan Baez, Woodstock ’69.

Dylan himself reflects on the song in his Chronicles Vol. 1. Quite extensively, as a matter of fact. It is a fascinating passage in Chapter 2, “The Lost Land”, in which he tries to recall how he started songwriting. The song “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night” and the story behind it is a trigger, at any case.

The life story of the activist immigrant fascinates him, but Dylan then retells it with remarkably little accuracy. For example, he casually mentions that Joe Hill fought in the Mexican War – that war was thirty years before the birth of the Swede. And Dylan tells that Hill was hanged and with his head in the noose spoke his last words, “Scatter my ashes anywhere but Utah.”

Joe was not hanged, but shot and his last words were: “Fire – go on and fire!”

A few years later, when radio maker Dylan plays the Baez version of “Joe Hill” in his Theme Time Radio Hour (episode 73: “Joe”), he apparently has been updated, he corrects the inaccuracies and tells the historically correct story.

Dylan ponders on that song. It doesn’t do Joe Hill justice, he says. He would do it differently and immortalize Hill more like a Jesse James or a Casey Jones. That would also create a nice circle; one of Hillström’s better-known songs is called “Casey Jones – The Union Cap”. Dylan already has a title: “Scatter My Ashes Anyplace But Utah”, and after that he considers modelling that song about Joe Hill on “Long Black Veil”. But alas, although he says he is thinking about how to approach such a first self-written song, it never comes that far. I didn’t compose a song for Joe Hill.

Well, not in those embryonic years anyway, the artist means. In 1967 the old fascination flares up again, when Joe Hill under yet another new alias finds a place on that beautiful album full of itinerant vagabonds, martyrs and outlaws, on John Wesley Harding.

The genesis is romantic. Dylan interrupts his months of playtime with the guys from The Band in West Saugerties and gets on the train to Nashville. That is a journey of some two days and it is tempting to think that Dylan is sitting there in a coupe, writing in his notebook the lyrics for the upcoming LP. In any case, there is no trace of it on The Basement Tapes and Band member Robbie Robertson also knows for sure Dylan did not play anything of John Wesley Harding in the basement of the Big Pink.

On the other hand, we have the testimony of mother Beatty Zimmerman, who in those days regularly stays with Dylan’s young family: Bob “continuously getting up and going over to refer to something” in the “huge” King James Version of the Bible that is always open, on a stand in the middle of his study.

Half quotes, Bible references, and Biblical language – it is all to be found on John Wesley Harding, so that notebook probably says a few things – which then gets completed on the train or at Nashville’s Ramada Inn, where Dylan is staying.

Very different from Blonde On Blonde, as the studio musicians and producer of that previous masterpiece also notice. During the recordings for that LP, the musicians played cards and ping-pong for days while Dylan wrote the songs in the studio, there was no limit to studio time and plenty of room for experimenting with arrangements and deviating instrumentation. Now the songs are already finished and in no time they are on tape with a minimum of instrumentation – apart from a single steel guitar in the last two songs, the job is done by just bassist Charlie McCoy, drummer Kenny Buttrey and Dylan.

“I Dreamed I Saw St. Augustine” is recorded immediately during the first session, October 17, 1967. And during that session, which lasts only three hours, “Drifter’s Escape” and “The Ballad of Frankie Lee and Judas Priest” are recorded too.

Of course, Dylan borrows the title, the opening lines and the circle structure from Joe Hill, but otherwise, as promised, he takes a completely different approach.

In line with the majority of the songs on John Wesley Harding, the language is archaic, taken from the King James Version of the Old Testament. Here Dylan draws primarily from the Book of Daniel, it seems; that book describes many visions and dreams anyway, and in there we also come across the three kings from the LP’s liner notes, the exclamations Lo and Behold, which Dylan saves for the Basement Tapes song, but especially that remarkable idiom. Ye, gifted, arise, utmost, fiery, just to name a few.

Dylan has to bend over backwards every now and then to get those words in and may still slip one or two times (“whom already have been sold”?), but apparently the poet thinks evoking the Scriptural sphere is more important than flawless grammar.

Either way, it works. And then partly thanks to the Kafka-affiliated style and theme. In terms of content, the lyrics have the same opaque clarity, the realistically described irreality as Der Prozeß (The Trial). Therein, the main character Josef K. is in the same state of upheaval as the I-person here; feeling guilty without being guilty, and also ending up lonely, anxious and in shame.

Dylan’s choice of perspective is a great find and comes close to his envisioned ideal from Chronicles. The protest song shouldn’t be preachy, he argues, not one-dimensional. “You have to show people a side of themselves that they don’t know is there.”

In St. Augustine, the protagonist dreams that he was on the jury that sentenced Joe Hill to death, and now is consumed by the insight that he killed an innocent, a saint even. The ambiguity is masterful; the narrator dreams having a vision. The shame, loneliness and anger are real, but the reason is not – after all, it is just a dream. Only apparently unambiguous is the name; however, this St. Augustine has nothing to do with a historical Saint Augustine – the same applies here as with the names in the songs, “John Wesley Harding” and “As I Went Out One Morning”, as with the landlord in “Dear Landlord” or Kafka’s parables and the New Testament parables: Go on, read, it does not say what it says.

The chosen musical accompaniment is sparse and brilliant. In the original, the slow waltz which Dylan will make from it just two years later (with The Band on the Isle of Wight), already shines through – the ripening process has done the song good.

The cover versions are almost always compelling. The men of the English / Australian ensemble The Fatal Shore build a stately cathedral of the song on their debut album (1997), the sympathetic Dirty Projectors record a warm, intimate living room version in 2010 and Thea Gilmore’s spine-chilling approach (Songs From The Gutter, 2005) gave her the courage to venture into an integral version of John Wesley Harding (2011, a glorious and brave album) a few years later.

Thea Gilmore:

John Doe’s cover on the I’m Not There soundtrack (’07) may be a bit overcrowded, but remarkable it is still, as it contains both echoes from The Band and Slow Train Coming. And even Joan Baez’s approach is tolerable for the Dylan fan with Baez allergy, on her Dylan tribute Any Day Now – incidentally with the original drummer, Kenny Buttrey, and also recorded at Nashville’s Columbia Studios (1968).

The most intriguing cover comes from an old slow hand and is on I Still Do (2016). It sounds like Eric Clapton unearthed a lost track from Ry Cooder’s chef-d’oeuvre Chicken Skin Music and then livened it up with his own chicken skin inducing guitar playing. Dramaturgically, Clapton’s singing does not come close to Dylan, obviously, but he knows quite well how to uncover the hidden melodic ore deposits – the quality in which Dylan himself has excelled for more than half a century.

Eric Clapton (sorry, it seems this video is not available in all parts of the world. In case that affects your viewing of the song there is a second edition beneath).

What else is on the site?

We have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with over 3330 active members. (Try imagining a place where it is always safe and warm). Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture.

The index to all the 597 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found on the A to Z page.

If you are interested in Dylan’s work from a particular year or era, your best place to start is Bob Dylan year by year.

On the other hand if you would like to write for this website, or indeed have an idea for a series of articles that the regular writers might want to have a go at, please do drop a line with details of your idea, or if you prefer, a whole article to Tony@schools.co.uk

And please do note our friends at The Bob Dylan Project, which lists every Dylan song in alphabetical order, and has links to licensed recordings and performances by Dylan and by other artists, plus links back to our reviews (which we do appreciate).

Yes, but your broad statement that the song “has nothing to do with a historical Saint Augustine” does not convince me that it doesn’t.

Augustine first be a “Gnostic” who considers that the physical world falls from a spiritual plane of light into one of darkness from which an individual can escape back to the light through the seeking of self-knowledge; then he converts to Christianity and beliefs more compatible with canons held by the Roman Catholic Church that an organization of religious authorities is necessary to lead the flock.

Many of Dylan’s song lyrics have a ‘gnostic’ slant to them though they are double-edged enough to be also interpreted from a Protestant point of view that claims Augustine as one of their own.

It seems to me that many of Dylan’s rolling lyrics gather moss from the ‘middle of the road” taken by poet Robert Frost.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/269/I-Dreamed-I-Saw-St-Augustine

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.