by Jochen Markhorst

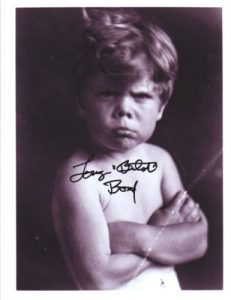

The poet Dylan undoubtedly envisions the archetype bully, the neighborhood bully from The Little Rascals, Tommy ‘Butch’ Bond, who played the role twenty-seven times between 1931 and 1938. Our Gang, as the series was originally called, began in 1922 and is still one of the most successful comic film series in history. Up to 1944, 220 episodes are recorded, feature and cartoon versions are being released well into the twentieth century (the 1994 cinema version is a hit), in the twenty-first century even coloured versions are re-released, and on Netflix The Rascals do well again in 2018, almost a hundred years after the first episode.

The poet Dylan undoubtedly envisions the archetype bully, the neighborhood bully from The Little Rascals, Tommy ‘Butch’ Bond, who played the role twenty-seven times between 1931 and 1938. Our Gang, as the series was originally called, began in 1922 and is still one of the most successful comic film series in history. Up to 1944, 220 episodes are recorded, feature and cartoon versions are being released well into the twentieth century (the 1994 cinema version is a hit), in the twenty-first century even coloured versions are re-released, and on Netflix The Rascals do well again in 2018, almost a hundred years after the first episode.

It is, therefore, a seductive, and most likely true, fantasy to imagine the little boy Robert Zimmerman sitting cross-legged on the living room floor in front of the telly, after the Saturday bath with combed hair in his pyjamas with a glass of lemonade, experiencing deep satisfaction when that mean bully Butch once again loses out.

Thirty years later that image from his youth looms up again when the protest singer ventures onto the politically slippery ice of the Israeli question. Although… “political”?

“I don’t consider anything that I write political,” as Dylan writes in the early sixties, in the (withdrawn) liner notes for “Let Me Die In My Footsteps” on The Freewheelin’ (1963). Until well into the 90’s this is a refrain in the interviews, sometimes unsolicited, but mostly as a reaction to a journalist who unsuspectingly uses the adjective “political”: “I don’t write political songs.” Even “Masters Of War”, Dylan declares defensively at a press conference in London, 1997, “is a very non-political song.” Remarkable, but even more remarkable is Dylan’s explanation: “I don’t know what politics is, to tell you the truth. I don’t know the difference of right-wing or left-wing. I don’t know those differences.”

The addition then confirms what we have suspected since the 1960s: Dylan has a rather private, simplistic conception of the meaning of the word “politics”. He seems to think it means something like “being active for an official political party”. Already in 1965, in an English interview with Ray Coleman, he argues quite naively:

“No politics. It would be just impossible for me to stand up and be associated with any political party. They’re all crap – every single one of them is crap. They all think they are better than the next one. Huh.”

In that light, Dylan’s commentary on the through and through political “Neighborhood Bully” is easier to grasp. Nonsensical, but still traceable within his own, simple-minded definition of “politics”:

“And Neighborhood Bully, to me, is not a political song, because if it were, it would fall into a certain political party. If you’re talking about it as an Israeli political song – even if it is an Israeli political song – in Israel alone, there’s maybe twenty political parties. I don’t know where that would fall, what party”.

(Rolling Stone interview with Kurt Loder, 1984)

“You can’t come around and stick some political-party slogan on it,” the bard clarifies. And in the Robert Hilburn interview, 1992, he’s still on the wrong track: “They call a lot of my songs political songs, but they never really were about politicians.” By the way, in that same conversation he admits, half-jokingly, to having written maybe one political song: “All Along The Watchtower”.

Granted, the term is not very clear-cut, but in general we mean something like “regarding the governance of a community’, in which community is understood very broadly. After all, we also do “politics” in the office space, at the football club, in the classroom and we already did in the sandbox.

And that’s where things go wrong, in all those interviews with Dylan. Journalists and radio interviewers who, quite rightly, casually refer to the political impact of “The Times They Are A-Changin’” or “Blowin’ In The Wind” really don’t think that those songs are meant as party political tunes for the Farmer Labor Party, the communists or the Republicans, but refer to the common, to the dictionary meaning of “politics”: meaning the songs highlight and comment on social power structures.

Oddly enough, Dylan’s reflex, the retort that his songs are not party-political songs, is never corrected. Awe for the man’s status or for his supposed intellectual superiority, presumably.

It is only in the twenty-first century that increased insight seems to descend. After some forty years of “not writing political songs”, Dylan suddenly says in 2001, in response to the humour in the songs of “Love And Theft”:

“Basically, the songs deal with what many of my songs deal with – which is business, politics and war, and maybe love interest on the side.”

(Rolling Stone interview with Mikal Gilmore).

Suddenly claiming, without blinking his eyes, that the songs of “Love And Theft” are just like “many of my songs” political.

Shortly afterwards, in the autobiography Chronicles Vol. 1, the writer uses the term (finally) in the common, universal sense. Looking back, Dylan will probably then qualify “Neighborhood Bully” as a political song after all, in a Chronicles Vol. 2 that will hopefully be released someday.

The song is an odd song out in Dylan’s catalogue, similar to the position of a “Give Ireland Back To The Irish” in McCartney’s portfolio or Sting’s “Russians” – simplistic, one-dimensional, pamphlet-like songs about complex, politically loaded problems. Dylan gives the song some literary cachet by making an allegory of it, by introducing a personified “Israel” as a thinking and acting man, as “just one man”. Personifications the poet Dylan uses all the time, in all the decades of his writing career, but he rarely writes allegories. “Dignity” is the clearest exception, other songs could be considered allegorical, but are poetically vague enough to escape that stamp (“Maggie’s Farm”, “Dear Landlord”, “Man In The Long Black Coat”, to name but a few).

That attractive, misty, Dylanesque poetic vagueness lacks the unique “Neighborhood Bully”. All right, the choice of title echoes a romantic, nostalgic residue from his Minnesota youth, and at most the last two lines are, in terms of literary sparkle, out of tune as well. But that’s all. The lyrics themselves are unsubtle, disparate and even a bit pushy, they reveal the same kind of Calimero complex as we already know from “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”: no matter how well-intended and even admirable the protagonist operates, “they” stone him. The power of the ironic reversal to consistently refer to the good guy as “bully” is milked out after two verses but is then still served up for another nine verses – no Dylan glasses are rose-tinted enough to be touched, surprised or moved for that long.

Outside Israel, the lyrics do not make many waves. In reviews of Infidels the song is usually ignored, maybe mentioned without much clangour of clarions, focusing mainly on Dylan’s passionate singing, the guitar duel of grandmasters Knopfler and Taylor, and the driving, gospel-rock-like musical accompaniment.

Bordering on embarrassed disregard, all in all, which seems to be shared by the master. In the studio he still devotes quite some time, by his standards, on a definitive recording (returning to it a month later, this time with Rolling Stone Ron Wood on guitar), but after that the song disappears into the drawer; Dylan never plays the song on stage.

Not even when he’s in Israel, in 1987. When journalist Robert Hilburn asks, a day after the concert in Tel Aviv, the master acts surprised:

“I hadn’t even thought of that song. I probably should have but I didn’t. It would seem to be an appropriate song. Maybe I’ll play it in Germany (laughs).”

Not very convincing. Dylan has, as always, thought carefully about the setlist, performs a surprising finale, the very Jewish “Go Down, Moses” (with the refrain line Let my people go) and two days later in Jerusalem he plays a totally different set (in extremis; not one single song is repeated), again without “Neighborhood Bully”.

Perhaps he shies away from the song’s charge and the propagandistic abuse that can be (and is) made of it. An understandable reticence, as is evident after a look at the internet forums where the song is discussed. On the American expectingrain.com, the British Untold Dylan, on YouTube… inviting a discussion about the song immediately gets out of hand, turns into poisonous, intolerant bickering about Palestine, bombings, UN resolutions, Gaza and arms supplies, in short: into the well-known, fruitless hostile debate and flame wars.

In Israel, they do like it, though. As late as in 2016, the country’s oldest newspaper, the venerable Haaretz, recalls that “rare declaration of full-throated Israel support by a mainstream American rocker” in a short article on the occasion of Dylan’s seventy-fifth birthday. The journalist Gabe Friedman states in the article that “some of the lyrics sound like they could have been taken from a speech by Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu” and that other lines “are reminiscent of the 2015 campaign ads for religious Zionist political party Habayit Hayehudi (The Jewish House)”.

Writer and university lecturer Adeyinka Makinde reports from Westminster University that the song is particularly popular with the Likud, as an “after-party conference boogie-down number” and according to the Jerusalem Post it is “a favourite among the Dylan-loving residents of the territories”.

There is, therefore, a slight disappointment when Dylan does not play “Neighborhood Bully” at any of his six concerts in Israel (1987, 1993 and 2011). Which is, in itself, not too surprising. After all, Dylan himself is, as we all know, perhaps the biggest bully of them all.

Publishers’ footnote: As is noted in the article above when this song was reviewed previously, the commentary immediately degenerated into political, religious and economic assertions without evidence, and as Jochen says, “into the well-known, fruitless hostile debate and flame wars.” As a result I was forced to ban numerous readers from commenting on the site, and remove a large number of posts. You may feel it unreasonable and unfair, and you may feel that your comment is perfectly legitimate and worthy of publication, but in this case you’re not making the decision. If I think the comment is unhelpful it will be removed. If I think it is very unhelpful the author will be banned. Autocratic, dictatorial, pathetic, unreasonable … yes my approach probably is all of those, but I have better things to do with my time as publisher of Untold than mediate political argument. On the other hand if you would like to comment on the chord structure, guitar work, or use of phrasing, in a non-political, non-aggressive manner, that’s fine by me.

“We live in a political world.” Bob can’t pretend not to know what the word means!

There is no way of intellectually understanding Dylan’s creative imagination without considering the mystical processes and experiences that unfolded in his inner life. But, you would have to first consider there is an inner life that brings inspiration and experiences making the world and its societies, with its collective intelligence and ignorance a thing the true poet comments on from a mesa above the pollution and the fray in a world of warring opposits.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/439/Neighborhood-Bully

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.