by Jochen Markhorst

Waylaid, the past participle of to waylay, is a beautiful, archaic and striking word in the otherwise rather poor lyrics to “Do Right To Me Baby”. In this century the use of it appears more often than in the centuries since 1513, since the first registered use of waylay, but the synonym to ambush is and remains much more common.

Waylaid, the past participle of to waylay, is a beautiful, archaic and striking word in the otherwise rather poor lyrics to “Do Right To Me Baby”. In this century the use of it appears more often than in the centuries since 1513, since the first registered use of waylay, but the synonym to ambush is and remains much more common.

Dylan’s country hero George Jones mentions the word once (in 1963, in “Big Harlan Taylor”), at Shakespeare it can only be found twice (in Twelfth Night and in Henry IV) and also Dylan only uses the word twice. Both times in 1978, by the way: not only in this song but also in the ambitious “No Time To Think” (which he actually writes in December ’77). And that’s not the only similarity between both songs.

Stylistically they could not be more different, of course. “No Time To Think” (from Street Legal) is an explosion of eloquence, of bizarre rhymes, rhythmic masterpieces and virtuoso language. “Do Right To Me Baby” is a thin, monosyllabic, somewhat droning, straightforward text. Which is illustrated by the scoreboard statistics as well: No Time has 288 unique words, Do Right only 80 – less than an average nursery rhyme. Of course, quantity doesn’t mean everything, but it does say something. At the very least, the most word-rich pop poet shows himself here, in a lyric of 323 words, from a remarkably gruff side.

But, strangely enough, both songs seem to be in line with each other in terms of content. In “No Time To Think” the poet also slaloms past universal, eternal vices, sins and temptations that have threatened the salvation of the human soul since the beginning of time. To this end, he stamps, verse after verse, masterfully poetic, pseudo-clear-cut Big Words (“Memory, ecstasy, tyranny, hypocrisy”) on mysterious imagery, symbolically loaded (“Mercury rules you and destiny fools you / Like the plague, with a dangerous wink”). It is dense, intellectually challenging, through-composed poetry, which a few months later, with “Do Right To Me, Baby”, he seems to rewrite into a child-friendly dummy version. By loyalty, dear children, Uncle Bob means “Don’t wanna cheat nobody, don’t wanna be cheated”, gravity is a difficult word for “Don’t wanna amuse nobody, don’t wanna be amused”, tenderness is the horror we try to avoid when we say, “Don’t wanna touch nobody, don’t wanna be touched”. And like this, all those don’ts seem to connect with Big Words and verse fragments from No Time, with the reflections the poet Dylan apparently has on his mind, these months.

The man Dylan is at a much-discussed crossroads these months. After his painful divorce, the bard stumbles into the Vineyard Christian Fellowship Church with the help of friend Mary Alice Artes, converts to Christian and a few months later astounds the world with the beautiful but frighteningly evangelical record Slow Train Coming. Dylan himself can pinpoint the exact turning point. On 17 November 1978, towards the end of the long, exhausting tour of 1978 (ten months, 114 concerts in ten countries) Dylan is in San Diego and someone from the audience throws a silver cross on stage.

“Now usually I don’t pick things up in front of the stage. Once in a while I do, but sometimes, most times, I don’t. But I looked down at that cross. I said, ‘I gotta pick that up.’ I picked up that cross and I put it in my pocket. It was a silver cross, I think maybe about so high. And I put it … brought it backstage with me. And I brought it with me to the next town, which was off in Arizona, Phoenix. Anyway, when I got back there I was feeling even worse than I’d felt when I was in San Diego. And I said, ‘Well I really need something tonight.’ I didn’t know what it was, I was using all kinds of things, and I said, ‘I need something tonight that I never really had before.’ And I looked in my pocket and I had this cross that someone threw before when I was in San Diego.”

And even more dramatic is his testimony that, lonely and alone in a hotel room, he felt the Hand of Jesus.

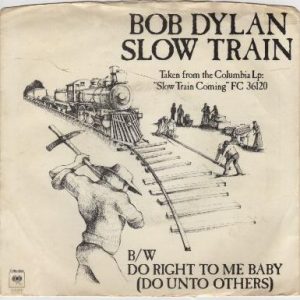

In these days he writes the first two songs that will appear on Slow Train Coming: “Slow Train” and “Do Right To Me Baby”. “Slow Train” is hardly evangelical and fits in better with Street Legal in both style and content, but “Do Right To Me Baby” is Dylan’s first, real attempt to proclaim the Good News, the prelude to that startling conversion.

This particular Glad Tiding is taken from Matthew, chapter 7, verse 12: “Therefore all things whatsoever ye would that men should do to you, do ye even so to them”. So the title and the chorus are gospel in the true sense of the word: “good message”.

However, it is the only biblical adaptation in the song. All those don’ts from the verses still seem (partly) in line with the commandments, rules of conduct and the guidelines from the New Testament Gospels, but the tone is really completely wrong. The opening line for example; don’t wanna judge nobody, don’t wanna be judged. It is true, Jesus says “Judge not, that ye be not judged” (Matthew 7:1), but in the verses that follow he explains what he means: that he abhors hypocrisy and calls to a self-critical gaze, illustrated by the metaphor of the mote in thy brother’s eye and the beam in your own eye.

The narrator in Dylan’s song strikes the tone of the bored, annoyed adolescent who wants to put an end to his mother’s sermon: “I don’t care enough to have an opinion, and moreover, I don’t want to be judged.” That is quite contrary to what the same New Testament tells us, not to say heretical – you most certainly will be judged, whether you like it or not. If not immediately after your death, then at the latest on Judgement Day. In Matthew alone it is four times announced; ye shall be judged in the day of judgement.

The narrator maintains this bored, annoyed tone in all the verses; it is mainly a list of activities with which he or she does not want to be bothered. Most of them belong to the domain of ordinary, everyday decency. Don’t hurt, don’t shoot, don’t cheat and don’t betray. Some are hardly to be taken seriously (“I don’t want to be amused”?), others border on absurdism (“I don’t want to marry someone who’s already married” – yes, we have laws against that, for a while now).

Dylan writes the text before attending pastor Gulliksen’s Bible lessons, that much seems clear.

Nevertheless, the song has great value for every Dylan fan. First of all for music historical reasons: it is the first song of the evangelical Dylan, the first Christian revelation Dylan introduces us to. He fumbles it, hardly noticeable, somewhere into the end of the setlist at the very last concert of that 1978 tour, at the Hollywood Sportatorium, near Fort Lauderdale, Florida, on December 16, 1978. Dylan is quite elaborate, if not loquacious that night, joking and fooling around with the musicians, but “Do Right To Me Baby”, a world premiere after all, passes without any comment, is not even announced or looked back on.

And secondly, because of the music. The richness of melody and rhythm changes, the subtleties and loving interpretation at all, and the beautiful ebb and flow of tension building and de-stressing are probably largely due to producer Jerry Wexler and session guitarist Mark Knopfler, as we may deduce from that first live introduction, well before both greats got involved. This embryonic primeval version is still set up as a thumping, funky and sweaty rocker. In the recording studio in Alabama, Wexler and Knopfler cut out the diamond that shines on Slow Train Coming. Cut like a 10cc or Stealer’s Wheel pop diamond, but with even more facets; a country guitar plucks underneath the fluttering, funky bass, pianist Barry Beckett provides the soul and drummer Pick Withers performs the same paradoxical trick he just demonstrated on Dire Straits’ first record: playing tight and laid-back at the same time.

It elevates “Do Right To Me Baby”, in spite of its lyrics, to one of the many highlights of one of Dylan’s most beautiful albums. That’s what the master himself seems to think too; later live performances are grafted onto the studio version (and sometimes surpass that, like the one at the Warfield Theatre in San Francisco, November ’79).

As with almost all songs from Dylan’s Christian catalogue, colleagues are a bit hesitant; the song is not covered much, not even in gospel circles. Tim O’Brien’s bluegrass is usually nice, sometimes very successful (“Tombstone Blues”, for instance), but here it’s no more than amusing (on Remember Me, with sister Mollie O’Brien, 1992).

Very nice is the Norwegian Tina Lie with a heavy blues and a fine band (on Free Enough To Fall, 2009).

The nicest, catchiest cover, the one by Clinton Collins & The Creekboys (Junebug, 2009), isn’t sky-high either, but it’s nice, acoustic, folky bluegrass country – Collins turns it into pure Americana and that does fit, one could say – if one were allowed to judge, that is.

Clinton Collins & The Creekboys

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 5500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

But what is complete is our index to all the 604 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found, on the A to Z page. I’m proud of that; no one else has found that many songs with that much information. Elsewhere the songs are indexed by theme and by the date of composition. See for example Bob Dylan year by year.

Tony this is to your best writing to date. I can only defer to Jakob Dylan “Up on the Mountian”. A Father and Son song that becries , “But theres a bright ,bright light makin its way up on the Mountain But you wont abandon your Masterpiece you wont surrender your Masterpiece and you will deliver your Masterpiece”.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/157/Do-Right-to-Me-Baby

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.