by Jochen Markhorst

The name of the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan will forever be linked to the librettist of his most successful operas: Gilbert, Sir William Schwenck Gilbert.

The name of the composer Sir Arthur Sullivan will forever be linked to the librettist of his most successful operas: Gilbert, Sir William Schwenck Gilbert.

In the twenty-first century both names live on in the stage name Gilbert O’Sullivan, whose songs still make it to the radio, the retrospects and The Sounds Of The Seventies compilations, but that is of course not the greatest merit of those artists from the nineteenth century.

In the English-speaking world, their fourteen comic operas, the so-called Savoy Operas, are indestructible. The most popular ones are still being performed (The Pirates Of Penzance, for example, and H.M.S. Pinafore), one-liners and quotes from the operas have entered the vernacular (“hardly ever”, for instance) and the best-known pieces are part of the British collective awareness.

However, Sullivan produced the greatest hit of the nineteenth century without Gilbert: the song “The Lost Chord”, which he composed in 1877 at his brother’s deathbed on a poem by Procter.

The song is an instant success, the great artists of those years put it immediately on the repertoire and the sheet music flies like hot cakes cross the counter. The American Antoinette Sterling spreads it around the world, the popular Fanny Ronalds, also Sullivan’s secret lover, identifies herself so much with “The Lost Chord” that a copy of the song manuscript goes into her grave at her request in 1916, in 1888 Edison plays a recording of the song at the introduction of his phonograph and in 1912 Caruso sings it at the commemoration ceremony of the Titanic disaster.

The persiflage “I’m The Guy That Found The Lost Chord” by American comedian Jimmy Durante (in the film This Time For Keeps, 1947) doesn’t really stand the test of time, but it does inspire a classic in the 60s: In Search Of The Lost Chord, the acclaimed third album of The Moody Blues from ’68.

The lost chord, both Sullivan and Durante find, is a chord with a small dissonant – one like that remarkable G+ that Dylan plays in “God Knows”. Apparently, it opens heavenly vistas: in “The Lost Chord” it is divine, and according to the lyrics it sounds like “a great Amen”. With Durante it leads to an almost religious ecstasy and Dylan has not found that G+ under a pagan stone either.

Basically, it’s a triad, a common major chord, but with augmented fifth, a chord produced by widening the perfect fifth by a semitone – a slight dissonant to Western ears. The first time Dylan plays such a chord is in his religious phase, when he plays “Rise Again” by Dallas Holm, a beautiful song from 1977 that CCM Magazine considers to be one of the 100 Greatest Songs In Christian Music.

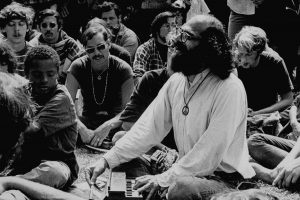

Dylan performs it a dozen times, Clydie King sings along, and those performances are all beautiful (Portland, December 3, 1980 is a very successful one). For The Bootleg Series 13 – Trouble No More 1979-1981 (2017) unfortunately only a rehearsal is selected. That is a wonderful, sober version, with excellent vocals of King and Dylan, only accompanied by Dylan’s acoustic guitar – illuminating that heavenly, “lost” chord all the better (it is the second chord, on “drive the nails”, for instance, and on “say it isn’t me”).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0NITuVaGZbU

For the sake of completeness it should be noted that around the same evangelical time, a few months earlier, Dylan also plays the G+ – in the ascending tonal order of “In The Garden” the organ climbs via that elevated fifth from G#m to Cm. More of a step in a slowed down loop than a well thought out compositional find, less distinctive than in “Rise Again” and in “God Knows”, but still. By the way, poet and friend Allen Ginsberg takes the credits, in a 1989 interview in Goldmine, for those gradually rising chords:

“I think I invented the chord-change in In The Garden. We went around trick-or-treating in Zuma Beach in masks, and I had my harmonium, and I was playing a funny ascending chord thing, where you just move one finger at a time.”

In the original, rejected version, the version that Dylan recorded with Lanois in the spring of 1989 during the sessions for Oh Mercy, the lost chord has not yet been found, according to the recording that is released on Tell Tale Signs, the eighth part of The Bootleg Series. That’s not the only difference; almost every line of text is different. In the months up to January 1990, when Dylan records the version for under the red sky, he rewrites the entire lyrics. Or at least selected other verses, which is at least as likely.

Dylan the poet has, according to his own words, a tendency to overwrite, to write more than necessary and has already sung several versions with Lanois, in March and April ’89. Not unusual with great songwriters; Leonard Cohen, for instance, writes more than eighty verses for his magnum opus “Hallelujah” and has never been able to choose a definitive version. Coincidentally also the song that sings a “secret chord”, by the way (Now I’ve heard there was a secret chord / That David played, and it pleased the Lord – only to reveal in the next line how that chord goes, so not that secret).

Presumably Dylan also has, just like Cohen has and just like Dylan has for a song like “Dignity”, about twenty verses for “God Knows” and lets the whimsy of the day decide, when he’s in the studio. This is apparent as well in the live versions after January 1990; there Dylan the singer browses left and right in the various versions, seemingly adding and deleting verse fragments at random.

The word combination God knows is a strong trigger, apparently, and Dylan’s inspiration may have been lit by Chekhov, whose short stories he admires so much. Бог знает (“Bog znaet”), God knows, is Chekhov’s favourite stopgap; in the Collected Short Stories alone it appears hundreds of times.

The alternative versions usually have a somewhat friendlier opening than the official one, the version on the site and in The Lyrics 1961-2012. Those versions open with God knows I need you or God knows I love you or God knows I believe you, all friendlier anyway than God knows you ain’t pretty.

That, and the fact that the verses are apparently interchangeable, suggests that Dylan is not dealing here with a lady, fictional or otherwise, but that the you is a personification, that the author poetically expresses his concerns about the vulnerability of an unnamed subject. Earth, perhaps. In this phase of his creation, Dylan does show some environmental awareness every now and then, hinting at ecological pain points.

On The Traveling Wilbury’s “Inside Out” (the grass ain’t green, it’s kinda yellow), in “Everything Is Broken” (Take a deep breath, feel like you’re chokin’), on this album in “2X2” (How much poison did they inhale?) and in the title song (the river went dry) and here in this song there is a river that no longer flows. The producer, the sympathetic Don Was, gets a vague suspicion when they record “Under The Red Sky” and decides to ask the man directly: “Is this song about ecology?” Dylan answers, without missing a beat: “No. But it won’t pollute the environment.”

Dylan likes to play “God Knows” on stage. Almost two hundred times, until 2006. It often is a nice boost of the set, usually they are driving, rocking versions of a song that stands out on under the red sky as well. However, neither that stage exposure, nor the inclusion of the Oh Mercy version on Tell Tale Signs leads to much recognition. There are hardly any covers – in fact only the tribute bands, dutifully, put a generally bloodless version on the repertoire.

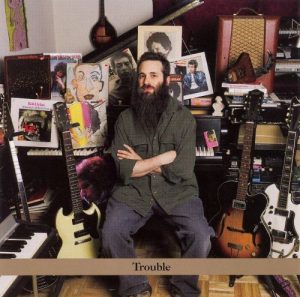

The exception comes from the jazz world. In 2006, the Jamie Saft Trio record a wonderful, special tribute to the master with the album Trouble.

The liner notes are alarming, promising a crippling respect for the bard. “Every man has his rabbi – let me introduce you to mine,” the Jewish Jamie Saft writes, and he explains in detail why he allows himself little freedom with the songs: they are, in Jamie’s opinion, already radical enough of themselves.

Luckily, he is not that respectful in deed. Although the trio plays very recognizable interpretations of the songs, the men most certainly do not feel limited by the original versions. The brilliant, sixties lecture of “Dignity” starts off with the intro of “Rainy Day Women # 12 & 35”, “Living The Blues” gets a Roaring Twenties arrangement and is sung beautifully by guest vocalist Antony, and the track selection deserves compliments too.

Of the eight songs, only “Ballad Of A Thin Man” is one of the more predictable choices on a tribute album, the other seven are songs that are skipped by everyone else: “Trouble”, “Disease Of Conceit” and “Dirge” (Michael Moore’s cover, with Jewels & Binoculars, of “I Pity The Poor Immigrant” is arguably the most beautiful jazz rendition of a Dylan song, but this “Dirge” comes close).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ik1AToDgveg

And “God Knows”, of course, the song that no seasoned jazz fan could ignore, if only because of that dissonant G+ – the penetrating, harmony-disturbing d# is gratefully milked out by the gifted pianist Saft.

Jamie Saft Trio – God Knows: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZcemrVDTYtE

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a subject line saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with approaching 6000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

But what is complete is our index to all the 604 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found, on the A to Z page. I’m proud of that; no one else has found that many songs with that much information. Elsewhere the songs are indexed by theme and by the date of composition. See for example Bob Dylan year by year.

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/213/God-Knows

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.