by Jochen Markhorst

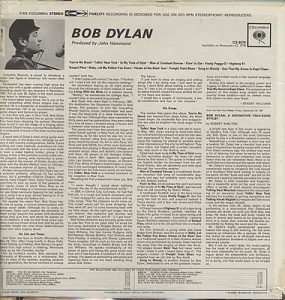

“He is one of the most compelling white blues singers ever recorded. He is a songwriter of exceptional facility and cleverness,” rouse the liner notes on Bob Dylan (1962), and “he’s an uncommonly skillful guitar player.”

“He is one of the most compelling white blues singers ever recorded. He is a songwriter of exceptional facility and cleverness,” rouse the liner notes on Bob Dylan (1962), and “he’s an uncommonly skillful guitar player.”

Well all right, the vocal qualities may still fall into the category beauty is in the ear of the beholder, but “uncommonly skillful guitar player”? Even Dylan must have read that back with some embarrassment, and rightly so.

“Bob’s musical ability is limited, in terms of being able to play a guitar or a piano,” as Mark Knopfler says. Quickly adding how unimportant that is:

“It’s rudimentary, but it doesn’t affect his variety, his sense of melody, his singing. It’s all there. In fact, some of the things he plays on piano while he’s singing are lovely, even though they’re rudimentary. That all demonstrates the fact that you don’t have to be a great technician. It’s the same old story: If something is played with soul, that’s what’s important.”

The blues music, however, has turned out to be a great, constant and lasting love – we can at least agree on that after sixty years. The liner notes on the successor The Freewheelin’, a year later, analyse confidently that Dylan has already gone through a big change since the last album, has moved to the top of the folk movement, and predict – bull’s eye – that “there will surely be many further dimensions of Dylan to come” in the future. Writer Nat Hentoff, though, acknowledges that the blues has been able to hold its ground, alongside all those folk songs, with traditional sounding songs like “Down The Highway” and “Honey, Just Allow Me One More Chance”. On the following albums and throughout the decades, up until Rough And Rowdy Ways in 2020, this shall remain so. The blues content varies, true, sometimes evaporating completely, but always returns – the blues is intrinsic to Dylan, deeper anchored than, for example, folk music.

On record number three, The Times They Are-A Changin’ (1964), there is not too much room for the blues between all those finger-pointing songs, on successor Another Side Of it slowly crawls back, and on Bringing It All Back Home Dylan’s beloved style of music shines and is born again: the minstrel embraces the electricity, and in doing so the Chicago blues. The band’s playing is bursting with joy – and not just with the blues. Dylan is playing electric and with a band for the first time since high school, and is audibly having a lot of fun.

“Outlaw Blues” is a highlight in that respect. Raw, carefree and unpolished, with the rattling exuberance of schoolboys in a garage band and the energy of the rhythm and blues over the simple blues scheme of Robert Johnson’s “When You Got A Good Friend”.

Ain’t it hard to stumble And land in some funny lagoon? Ain’t it hard to stumble And land in some muddy lagoon? Especially when it’s nine below zero And three o’clock in the afternoon

The lyrics are food for music historians and Dylanologists, which is part of the special charm of this song. Actually, the song marks the blossoming of the kaleidoscopic lyricist Dylan, announcing the string of superb highlights on Side 2, like Tambourine Man and It’s Alright Ma. “Outlaw Blues” is a first step on that stellar path.

For starters, the thief of thoughts lovingly raids the blues catalogue. The opening Dylan borrows from “Stranger Here”, which he probably knows through the version by Odetta:

Ain't it hard to stumble When you got no place to fall Ain't it hard to stumble When you got no place to fall Stranger here Stranger everywhere I would go home But honey I'm a stranger

…and the associative leap from stranger to outlaw is not that big. Equally associative are the half and whole references to blues heroes in the remainder of the first verse. To “Nine Below Zero” by Sonny Boy Williamson II, “Three O’Clock Blues” by B.B. King and, well all right, half a wink to Muddy Waters.

It opens the gate to the rest of the lyrics, to the nonsensical outbursts, semibiographical veils and Americana;

Ain’t gonna hang no picture frame Well, I might look like Robert Ford But I feel just like a Jesse James

As in this second verse, Jesse James’s death scene, who was shot in the back by the coward Robert Ford while hanging a painting over the sofa – crucial enough to become to song’s name-giver, apparently.

The cheerful nonsense of the third verse,

Oh, I wish I was on some Australian mountain range I got no reason to be there, but I Imagine it would be some kind of change,

is witty and has the merit of inspiring Arlo Guthrie:

We ought to send Officer Joe Strange To some Australian mountain range So we all can do the ring-around-a-rosy rag. (Ring-Around-a-Rosy Rag, 1967)

And in the fourth verse the poet once again places a real Dylan classic: don’t ask me nothing about nothing, I just might tell you the truth – the one-liner that, together with the sunglasses and the black tooth has been siphoned off from the song’s “primeval version”, from “California”.

And furthermore some loose snippets from the blues canon. The woman in Jackson is most likely from “Blue Bird Blues” by Sonny Boy Williamson (1937), the brown-skin girl from the song’s template, from Robert Johnson’s “When You Got A Good Friend” (She’s a brown skin woman, just as sweet as a girlfriend can be) and I love her just the same Dylan probably steals from Louis Jordan’s mega hit “Caldonia” from 1945:

Walkin' with my baby she's got great big feet She's long, lean, and lanky and ain't had nothing to eat She's my baby and I love her just the same Crazy 'bout that woman 'cause Caldonia is her name.

By the way, “Caldonia” is the first song in history for which the term rock ‘n’ roll is used in writing (in Billboard Magazine). James Brown releases his version of “Caldonia” on single a few months before Dylan records “Outlaw Blues” – one way or another it must have penetrated Dylan’s vocabulary.

In the verse one could find, with some good will, a few lines to biographical facts. Just as in the finale one may wonder whether that might be Joan Baez, the dark-skin woman whose name he won’t mention. After all, in previous years he did quite regularly visit her in California.

Thin, but in line with the misty, opaque nebulous poetry in which Dylan will become even more proficient, hereafter. And in line with the promise made by the master in the liner notes: I am about t sketch You a picture of what goes on around here sometimes. A vague drawing of unrelated fragments from a restless, multicoloured life… yes, that does sound very much like Dylan’s poetry these years.

Infectious it is anyway. Ain’t it hard when you stumble is a great opening line and the thrust of the simple blues riff remains irresistible throughout the decades – the song is on many setlists. Grace Slick picks it up back in ’66 (before Jefferson Airplane, with The Great Society), Dave Edmunds in the ’70s (with Rockpile), Dream Syndicate in the ’80s, with both Thin White Rope and The Radiators the song was on the playlist in 1992 and Dylan friend Jack White takes “Outlaw Blues” with his White Stripes into the 21st century.

None of the covers are presumptuous, nor display any ambition apart from having fun. The rugged garage sound is a Great Common Denominator and, although always enjoyable, no one refreshes the original.

The one exception is the studio recording by The Morning Benders (on the brilliant tribute project Subterranean Homesick Blues, 2010). They pull the song tight in a slow, dressed-down and dramatic arrangement, add ethereal backing vocals and produce a macabre, ominous version, very different, and very successful.

Uncommonly skillful guitar player, by the way.

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with approaching 5000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

But what is complete is our index to all the 604 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found, on the A to Z page. I’m proud of that; no one else has found that many songs with that much information. Elsewhere the songs are indexed by theme and by the date of composition. See for example Bob Dylan year by year.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/480/Outlaw-Blues

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.