by Jochen Markhorst

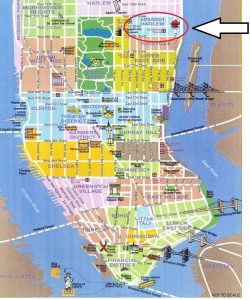

It is a mythical part of town, the part of Harlem between East 96th and 110th Street. Officially its name is East Harlem, but after nicknames like Negro Harlem and Italian Harlem (way back when one Al Pacino was born there), Spanish Harlem it has been since the 1950s. The Law of the Large Numbers – the Hispanics dominate, that’s why. The Spanish speakers themselves prefer El Barrio, though.

It is a mythical part of town, the part of Harlem between East 96th and 110th Street. Officially its name is East Harlem, but after nicknames like Negro Harlem and Italian Harlem (way back when one Al Pacino was born there), Spanish Harlem it has been since the 1950s. The Law of the Large Numbers – the Hispanics dominate, that’s why. The Spanish speakers themselves prefer El Barrio, though.

It’s quite a walk from Dylan’s West 4th Street. Two hours of walking, over 7th Avenue, crossing Central Park to East 79th and then still a reasonably long walk over 2nd Avenue.

With the subway it takes about three quarters of an hour. So not a neighbourhood where a Villager happens to pass by as he is going for a stroll. And anyway, East Harlem in the 60’s is a rather unattractive place to visit. Entire blocks of houses are down because of the many, endless urban renewal projects, so the remaining blocks are overcrowded, crime and drugs are rampant, arson is the most popular form of insurance fraud and gang violence disturbs the evening and night’s rest.

An ideal backdrop for an ominous love story, all in all. Dylan is not the only one who recognizes that. Opera director Peter Sellars, for instance, moves Mozart’s Don Giovanni to Spanish Harlem, Ben E. King loses all control when the Rose of Spanish Harlem sets his soul on fire (1960), in East Harlem Carlo abuses his Connie Corleone and is therefore beaten to pulp in the street by his brother-in-law Sonny (The Godfather I, 1972) and author Walter Dean Myers chooses El Barrio as the decor for an adaptation of the archetypical fatal drama with the archetypical fatal gypsy gal: Carmen.

It’s the contrast which fascinates, obviously. The extremely beautiful, exotic beauty amidst the extremely ugly, barren big-city wasteland returns as a motif so often in art history that it has already become kitschy – it is the erotic variant of the Bragolin’s Crying Gypsy Boy. But Dylan swears it really happened to him, this complex love story with a gypsy girl from Spanish Harlem.

The journalist Nat Hentoff is the lucky Wilbury who is allowed to watch Dylan recording Another Side Of Bob Dylan in the studio on 9 June 1964. He interviews the singer on the day itself and again a week later. While listening back to the recordings, the journalist is already sucking up: “The songs so far sound as if there were real people in them,” he generalizes. Dylan acts surprise at Hentoff being surprised about that:

“There are. That’s what makes them so scary. If I haven’t been through what I write about, the songs aren’t worth anything.”

And then the poet does not substantiate this – debatable – thesis with “It Ain’t Me, Babe” or “Ballad In Plain D” or “I Don’t Believe You”, but he elaborates with “a complicated account of a turbulent love affair in Spanish Harlem” (in The New Yorker of October 24, 1964).

Yeah, well. Fortunately, the truthfulness of the lyrics is of no importance at all. The content of the song holds an exceptional position. It is one of the very few Dylan songs in which the male protagonist hands himself over, bound hand and feet, to a woman he adores, without any nastiness or mocking distance – which is quite a contrast to the other relational songs on this LP.

Even more fascinating is the form. “Spanish Harlem Incident” marks a transition from the more conventional love lyrics on the previous albums to the psychedelic and visionary richness of the following Big Three. The flaming feet and restless palms are first explorations of the catachresis, the “wrong use”, the style figure in which Dylan will excel from the next record, Bringing It All Back Home. “Your temperature’s too hot for taming” is another one of them; a completely unknown, innovative combination of incompatible words, which seemingly has the power of an old-fashioned proverb – and meanwhile it’s neatly classical iambic and alliterative, grazing content-wise along the archetype of Carmen. Similarly, the love of this warm-blooded and hot-headed Carmen nul ne peut apprivoiser, cannot be tamed, as the unfortunate Don José will experience.

Different is also the music. The third take, with harmonica, is rejected by Dylan, and eventually the accompaniment is limited to the meandering guitar part in the final fifth take. It is a peculiar part; a shuffle with recurring escapades to half blues licks and over it the vocal lines, more melodious than we are used to. Those vocals Dylan delivers with an attractive sleepy, dragging intonation, matching the dreamy, unreal content of verses like I’m nearly drowning and I know I’m ’round you but I don’t know where. Which, by the way, are the first flashes of the Kafkaesque clarity Dylan will so superbly demonstrate on John Wesley Harding, a few years later. The clarity that is defined by Kafka as the so-called Laurenziberg-Erlebnis, the “Petřín Hill Experience”, in his Reflections From The Year 1920:

“To describe reality in a realistic way, but at the same time as a “floating nothing”, as a clear, lucid dream, so as a realistically perceived irreality.”

Dylan himself virtually ignores the song, though. He performs it one single time, five months after the recording, at the Halloween concert in the Philharmonic Hall in New York (31 October 1964), and, according to Björner, once more in 1990 during a rehearsal, of which there is no known recording. Perhaps the hybrid character of the song, the fish-and-fowl content, bothers him.

The Byrds quickly pick up the song. Their version is one of the four Dylan songs on their legendary debut album Mr. Tambourine Man (1965) and is, with McGuinn’s jingle-jangle twelve-string Rickenbacker, just as irresistible as the title song. Remarkable is the pathetic, somewhat overly majestic cover of Dion’s otherwise fascinating album The Return Of The Wanderer (1978). Still, it must have satisfied Dylan’s soul, an old hero like Dion singing one of his songs. And that is probably even more true for the nice performance by country dinosaur Buck Owens, mentioned by Dylan in the same breath with Hank Williams back in ’66 and honoured by him again in 2015, during that surprising MusiCares-speech in February: “Buck Owens has written “Together Again”, and that song alone surpasses anything that ever came out of Bakersfield” (a little sneer aimed at Bakersfielder Merle Haggard, who, according to the quasi insulted speaker, does not like Dylan’s songs). In country circles the song scores often anyway. Don Williams, back then a member of the Pozo-Seco Singers, lends his flexible baritone to a moody “Spanish Harlem Incident” as early as 1968 and bluegrass bands don’t shy away either (the Yonder Mountain String Band, for instance).

Entertaining enough, all of them, but none at the level of the enchanting Chris Whitley, who opens and closes his cover project Perfect Day (2000) with a Dylan song. The closing track of the album, “4th Time Around” is heart-breaking. The opening track then is “Spanish Harlem Incident” and it’s one of those rare covers that manages to step out of the master’s shadow. Sparingly orchestrated; a double bass, a percussionist who limits himself to brushes and one drum, and the Whitley’s guitar, who is holding back too, releasing only a fraction of his unique skills – in this case on his old steel guitar from the 30s, the Old Style-O, as it seems. The charm of his exceptional, hoarse, cracking and muffled voice is not without controversy, but with the slower songs, like this version of Incident, the impact is undisputed. Despite the chilly sound and bare arrangement, the song gets a warm, almost mystical glow, Whitley’s vocals enriching the song with both excitement and despair.

Boy, she surely is a fatal wildcat, this gypsy gal.

————————–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a subject line saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with approaching 6000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

But what is complete is our index to all the 604 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found, on the A to Z page. I’m proud of that; no one else has found that many songs with that much information. Elsewhere the songs are indexed by theme and by the date of composition. See for example Bob Dylan year by year.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/588/Spanish-Harlem-Incident

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.