by Jochen Markhorst

A P R I L, 1 9 7 0

Dear Fay,

Some people are going to get killed out of this situation

that is growing. That is not a warning (or wishful thinking). I

see it as an “unavoidable consequence” of placing and leaving

control of our lives in the hands of men like Reagan.

These prisons have always borne a certain resemblance to

Dachau and Buchenwald, places for the bad niggers, Mexicans,

and poor whites.

The logical place to begin any investigation into the

problems of California prisons is with our “pigs are beautiful”

Governor Reagan, radical reformer turned reactionary.

Governor Ronald Reagan of California participates enthusiastically, with the playful idea of an agent from Long Beach. At the end of the 1960s, the militant Black Panthers consistently call policemen pigs and that swear word begins to take hold. Officer Bernie Frydman believes in reverse psychology, invents the acronym Pride-Integrity-Guts-Service and initiates a “Pigs Are Beautiful” campaign with friendly happy pigs on ties, buttons, tie pins, cufflinks and posters.

Governor Ronald Reagan of California participates enthusiastically, with the playful idea of an agent from Long Beach. At the end of the 1960s, the militant Black Panthers consistently call policemen pigs and that swear word begins to take hold. Officer Bernie Frydman believes in reverse psychology, invents the acronym Pride-Integrity-Guts-Service and initiates a “Pigs Are Beautiful” campaign with friendly happy pigs on ties, buttons, tie pins, cufflinks and posters.

“I like it,” declares his boss, the future president Reagan, and he appears for a few weeks with a gilded pig as a tie pin at press conferences and television broadcasts.

The transparent attempt to turn pigs into an honorific, into a badge of honour, does not catch on. The officers are not suddenly proud to be a pig and to this day pig is just as insulting and as popular as it was in 1968. Even more popular actually; it’s now spread to all English-speaking countries.

In his collection of letters, the bestseller Soledad Brother, Black Panther George Jackson does not exercise any particular restraint either: 117 times the brave constables are indicated with the hated invective (twice with “policeman”, thirty times with “cop”).

Now, George Jackson deserves some consideration for being a little less nuanced. In 1961, at the age of 19, after a few juvenile offences, he is factually sentenced to life imprisonment. His crime: he is behind the wheel of the getaway car during a robbery at a gas station (where the loot is $71). After more than seven years in San Quentin, he is transferred to Soledad Prison in January ’69, where a guard shoots him in August ’71, officially during a violent escape attempt.

During his prison years, he has developed himself considerably – from petty criminal street punk to a well-read, leftist-intellectual philosophical activist with remarkable literary talents. His metaphors sometimes do derail slightly (“These prisons have always borne a certain resemblance to Dachau and Buchenwald, places for bad niggers” – after which Jackson ends his letters for a while with “From Dachau with love”), but he also scatters his writings with beautiful aphorisms (“I’m doing as I’ve always done, wish for five, expect three, and get nothing”), classical quotations (Jackson loves Shakespeare: “Let Rome in Tiber melt, and the wide arch of the ranged empire fall” from Antony and Cleopatra) and paraphrases the ideas of men like Kipling and Darwin to marble one-liners like “The jungle is still the jungle be it composed of trees or skyscrapers, and the law of the jungle is bite or be bitten.”

Dylan is fascinated, not only by Jackson’s colourful and tragic course of life, but also by the collection of letters. In songs like “Walls Of Red Wing” and “I Shall Be Released” the poet plays with the notion that the world is a prison, that we are all prisoners. Dylan’s reflex to elevate the prisoner to the status of hero is known from “The Ballad Of Donald White”, “Drifter’s Escape” and, later, from “Hurricane” and the songs about Hattie Carroll and Davey Moore demonstrate his compassion for black victims of a white, repressive system.

So George Jackson’s story is right up Dylan’s alley, leading to a rare flash of inspiration. Dylan’s well is empty in the dry years between New Morning (1970) and Pat Garrett And Billy The Kid (1973). He doesn’t achieve more than the songs “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece”, both inspired by his writing block. The apparent ease and remarkable speed with which “George Jackson” is written, recorded and released creates hope, also because of the old-fashioned, pre-’65 finger-pointing content of the song: is Dylan back?

The B-side of the single, the acoustic version, is in any case a return to old times. The instrumentation (guitar and harmonica only) and the simplified, dramatized distortion of the actual events is 1963 Dylan: “The Lonesome Death Of Hattie Carroll”, for example, including that philosophical finale.

Jackson himself divides the world into two distinct types only: the guilty and the innocent. Dylan embellishes that into the more poetic image some of us are prisoners, the rest of us are guards. There is also some excitement about the four-letter word shit, the first expletive in an official Dylan song. It is beeped by the mainstream radio stations, but alas, it does not generate too much extra attention.

Back at the top of the charts it does not bring him. A disappointing 33rd place is the single’s peak; like the press, the public is not too enthusiastic either. There are even cynical questions about Dylan’s sincerity – that the worn out protest singer would want to slip back into the hearts of his old fans over Jackson’s back (as if Dylan ever cared about the expectations of his admirers).

Neither does the recording mark a reopening of his creative vein – it will take some more time before the songs start flowing again.

No, no return, just an isolated burst. One that evaporates quite quickly. It almost seems as if the subject is too controversial, even for the master himself. Jackson is of course radicalized, embracing Lenin and Mao (“with them I found salvation”) and has – officially – the death of at least one prison guard on his conscience. So the single, with a band version on side A, does little and soon fades, just like the song at all; Dylan never plays it live, doesn’t select it for compilation albums and it’s hardly picked up by any of his colleagues.

In the Far East the song pops up again, on the compilation Masterpieces (1978) and a next official re-release takes until 2013, until the bonus disc at The Complete Album Collection Vol. 1.

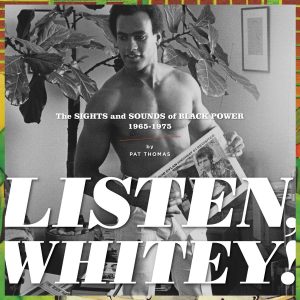

In the black community the song is more appreciated. As on the Sounds Of The Black Power collector Listen Whitey! – with on the cover Dylan fan and Black Panther founder Huey Newton cherishing a copy of his beloved Highway 61 Revisited.

In the black community the song is more appreciated. As on the Sounds Of The Black Power collector Listen Whitey! – with on the cover Dylan fan and Black Panther founder Huey Newton cherishing a copy of his beloved Highway 61 Revisited.

Of the rare covers, the reggae version of Steel Pulse (2004) has at least some conviction; their own “Uncle George” demonstrates passion and commitment to the cause as well. However, memorable music it does not yield, nor does the sterile live performance by Joan Baez. The only performance that is (more than) worth listening to is J.P. Robinson’s glowing soul ballad from 1972. An Otis Redding approach (especially the opening, in which he seems to slide down to “I’ve Got Dreams To Remember”), with horns, organ and ladies’ choir – an arrangement which works surprisingly well. And that languishing mouth organ certainly is a very nice reverence to the song’s spiritual father.

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics who teach English literature. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a subject line saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with approaching 6000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best.

But what is complete is our index to all the 604 Dylan compositions and co-compositions that we have found, on the A to Z page. I’m proud of that; no one else has found that many songs with that much information. Elsewhere the songs are indexed by theme and by the date of composition. See for example Bob Dylan year by year.

Nice article, thanks for including J.P. Robinson‘s version, too. But I still continue to enjoy listening to the original A and B sides. Thanks, again.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/208/George-Jackson

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.