By Tony Attwood

The first performance of Oxford Town came just two months after the first performance of Hard Rain’s a Gonna Fall, and yet Oxford Town sounds as if Hard Rain hadn’t happened. It is a beautiful powerful song, eloquent and emotional, but quite a different sort of composition.

So this is not to say that Dylan should have been developing Hard Rain (no one of course can tell him what he should be doing) but straight after Hard Rain he was back to writing a more traditional style of music. The fact that he could move between such different genres shows the power of his creative drive at this time.

Oxford Town itself resulted from a competition in Broadside magazine (issue 14) where the invitation was sent out for composers to write a song about James Meredith’s University of Mississippi enrolment. It was one of two very notable submissions – the other being “Ballad of Oxford, Mississippi” by Phil Ochs.

The magazine was one of those from the era which had a small circulation and was produced using fairly basic technology, but which had an influence far beyond its appearance and circulation. It was the heartland of the debate as to what was happening with pop, rock, folk, traditional music and so on.

The publishers were friends with Pete Seeger and Woody Guthrie, and strongly socialist in their outlook at and political activity. Music was seen as part of the drive for change and social justice. The magazine lasted for over a quarter of a century.

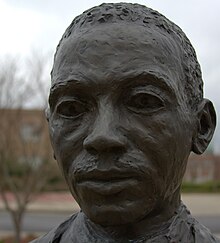

Analysis and review of the actions and work James Meredith within the American Civil Rights Movement are readily available and I do not mean to reduce his importance or the importance of the movement by not dealing with his work in detail. But because it is so widely covered on line I will just cover a couple of basics, perhaps primarily for friends in England where there were and still are racial issues, but where segregation followed a different route and the name James Meredith is not widely known.

In 1954 the Supreme Court in the USA ruled that segregation of public schools and universities was unconstitutional, as they were funded by all taxpayers. However although the federal government had asserted the right of all Americans to attend state funded universities regardless of colour, in reality many universities operated a policy of being white only. In 1962 Meredith applied for a place at the University of Mississippi and was ultimately the first African-American student to be admitted to the University. His aim therefore was encourage the national government to enforce what it had said was the right of all the population.

On 31 May 1961, Meredith, with the backing of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People took the university to court, pointing to his academic record and his service to the state in the military as justification for his having a place. Ultimately he won the case in the appeals court and again in the Supreme Court and in September 1962, the District Court directed the University to register Meredith.

The Democratic Governor of Mississippi opposed this, and the state passed a new law seeking to ban Meredith on the grounds of a previous criminal offence. The government overruled this, the Governor refused to admit Meredith, and the Governor was found to be in contempt and threatened with a fine $10,000 a day unless he gave way.

The Governor did give way, President Kennedy issued a “cease and desist” proclamation. When a mob gathered to stop the registration the National Guard was ordered in. Two men were killed in the rioting, as Dylan notes in his song. With the National Guard now in control Meredith was registered and this is seen as a key moment in the civil rights movement.

Meredith’s time as a student was extremely arduous as the protests did not cease but he gained a degree in political science in 1963, and others followed suit.

In using the phrase “Oxford Town” Dylan is (as I understand it from my distance of many thousand miles) using poetic licence; from what I read the University is described as being in Oxford, Mississippi, not Oxford Town.

And just as the song does not mention the university, the song also does not cite Meredith, but Dylan is quoted as saying “It deals with the Meredith case, but then again it doesn’t…” which is a fairly typical Dylan comment. He continues “‘Why doesn’t somebody investigate soon’ that’s a verse in the song.”

But although Dylan may have slightly changed the name of the location, the song had enormous power because of its absolute simplicity.

In the introduction the guitar rotates between two chords, and then continues to do this through the song, but it is in essence a song on one chord, with all the power coming from the melody. (Dylan once described it as a banjo song played on a guitar, and that chord rotation is most certainly reminiscent of banjo music).

Oxford Town, Oxford Town

Ev’rybody’s got their heads bowed down

The sun don’t shine above the ground

Ain’t a-goin’ down to Oxford Town

Even the opening verse tells us there is something deeply, seriously wrong here. Dylan doesn’t have to say why, because we know.

The rhyming structure is interesting though (although one hardly notices it until going back to seek it out). In verse 1 above we have lines 1, 2, and 4 rhyming. In verse 2 all lines rhyme.

He went down to Oxford Town

Guns and clubs followed him down

All because his face was brown

Better get away from Oxford Town

But then Verse three – one suddenly wonders “what does ‘around the bend’ mean?” In English English the phrase is slang for having a bizarre or odd idea. A person says “I’ve working on a time machine” and the friend replies, mockingly, “You’re round the bend”. Not such that it makes you insane, but that is just an odd, odd, thing to say or do. In that context it doesn’t seem at all strong enough for what happened at the university, so maybe there is another meaning in American English.

Oxford Town around the bend

He come in to the door, he couldn’t get in

All because of the color of his skin

What do you think about that, my friend?

One fears that perhaps it was just a throw away line to get a rhyme with the last line – and yet it seems quite unnecessary. The rhyming structure is already established as variable, and since “friend” is hardly essential to the meaning, one wonders why another phrase wasn’t used – unless there is an American meaning to the phrase “round the bend” that I don’t know. (Round the Bend is also a novel by Neville Shute, published 1951, which deals with religion’s relationship to good works, but that doesn’t seem to take us anywhere).

Verse four again seems to drift away from the point. The visit of the man and his lover and her child is hardly central, and seems only to be there to find a rhyme with “come” – although it is only a half rhyme. All the drive comes from the proper rhymes of lines 2 and 4. It is almost as if Dylan and his family stumbled across the issue while passing, which is again odd. This was national news.

Me and my gal, my gal’s son

We got met with a tear gas bomb

I don’t even know why we come

Goin’ back where we come from

But then after this we are back on track. The rhymes work and the urgent need for this to be resolved (in the last line) is made more powerful because the rhymes are working, and each line is vital to the song.

Oxford Town in the afternoon

Ev’rybody singin’ a sorrowful tune

Two men died ’neath the Mississippi moon

Somebody better investigate soon

And yet despite the fact that some of the lines appear to have been thrown in without deep thought, the song has the power because it is so simple and understated. A “this is the world we live in – we really ought to get this sorted” type of song, except that it is not “we” who need to take action, but rather “someone”.

Indeed that “someone” is the oddity, and it is odd that Dylan specifically mentioned that line in his commentary. He’s not doing anything, I’m not doing anything, there’s no call on the President. Just someone. Maybe that is the point. “We sit here stranded” waiting for others to act. (Mind you, I seem to be able to relate every Dylan song back to Johanna, so maybe not).

I personally find this very strange. I have known the song since its first release in the UK; I can even remember the record shop where I bought it with my pocket money as a kid. As I came to think about writing about it today, I could sing the whole song, get every word right and play the guitar part without listening to it again. It is there deep within me and I haven’t played it or heard it in years. And yet, I still find it curious, almost as if Dylan just wrote it and sang it, without going back to think, “couldn’t I say a little more there?”

Maybe he was being pressured to finish off his piece for Broadside, maybe he was already moving on to something else. Who knows.

But it is still a poignant, meaningful, powerful remarkable piece of music. I’m glad I’ve still got that original copy of the album all these years on.

Index to all the songs on Untold Dylan

For the origin of ’round the bend’ see:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Telegraph_Island

The reason behind the title of Oxford Town is that Dylan uses the English folk song, Nottamun Town, as model both for the metrics and the one-chord drone features of his song.

Best wishes

Michael

Michael, thanks for writing in. I appreciate the point, but really the melody of Nottamun Town doesn’t anything like Oxford Town, and it was sung as an unaccompanied piece (it is a mediaeval song, so any accompaniment came hundreds of years later). True, I only know the version that is popular in the East Midlands of England (where Nottingham is) but it really doesn’t seem to have in common with Dylan’s song.

Interestingly the Wiki entry on Nottamun Town says that it was used by Dylan as the basis for Masters of War, and that I can immediately hear.

Just my opinion of course, not trying to say this is right and that is wrong.

I think, at least, you will grant that the off-key titling of Dylan’s song-contest entry – as you remarked – could derive from his contemporary interest in English folk songs, a subject that would prove so profitable in the long run. ‘Oxford Town’ is an immortal song, but still a pastiche (of Nottamun Town), though that’s an opinion, of course.

One of the most interesting points about “Oxford Town” is its absolute relevance for contemporary American politics: make black lives matter, the geographic split between red and blue states, the culture of guns and violence particularly characteristic of the Southern states.

The devastating simplicity of the song renders it an even more powerful statement about these deep chasms splintering American society than more ambiguous songs like “Blowing in the Wind”. To be sure “Oxford Town” lacks the political sophistication of “A Pawn in Their Game” that develops a theory of how Southern racism kept down, suppressing the political voice of the dregs of white society.

Why the contemporary relevance? The obvious answer is that contemporary societies continue to struggle with their historical development: slavery versus the bill of rights in the case of the United States: Christianity and the Enlightenment in the case of Western Europe; political and military fragmentation in Europe versus a ideological drive to unify the Continent; French and British culture in the case of Canada; and so forth.

Michael, of course. With Dylan saying nothing much, we can only have opinions, and I do welcome all opinions here. Each one makes me re-think.

Always liked the understatement in the song. To me, as well as on the surface addressing the Meredith case, the song is critical of the limp response of the white liberals from northern states who see the civil rights movement as a ’cause’ to support and although good intentioned, they ultimately are tourists in a complex and deadly situation.

The opening verses deal in simplifications and understatements of events as the narrator sees them, who is so incensed by what is going on brings his gal and her son down to Oxford to lend support to Meredith and the civil rights movement. The reality turns out to be far scarier than imagined and they soon retreat to the comfort and safety of where they come from. The residents of Oxford however don’t have that luxury and are left behind to face shadowy murders which prompts the wholly inadequate cry from the narrator of “somebody better investigate soon”.

Interesting piece on Dylan’s finest–hands down–protest tune ever, though I think you probably are over-analyzing its rhymes.

You should know that when the late John Hammond [Sr.] was talking to Dick Cavett in New York City about Dylan’s import, it was the only song he cited as evidence of the recording artist’s genius.

Hammond was also in the Columbia studio the night Dylan recorded it. His reaction was the same as my own when I first heard it, although unlike Hammond, I didn’t vocalize it. That response? “It that it? Isn’t there more?”

BRYAN STYBLE/Florida

Zimmerman Blues 1975-79

As a freshman at Ole Miss in the Autumn of 1962, I was an eyewitness to the riot on the Oxford campus the night of Sunday, September 30, 1962, over the admission of the first Negro (James Howard Meredith) as a student. He was a native Mississippian and had served in the Air Force prior to 1962, and was a transfer-in senior who wanted to graduate from the flagship state university. After all these past 55 years since the riot, it still amazes me that the death toll was not much higher than the two men who were shot to death on campus that night. They are still considered cold cases. When I met with James Meredith in his home in Jackson, Mississippi, in 2001, we both agreed that full responsibility for the riot falls on segregationist Governor Ross Robert Barnett.

Hello Tony, yes another very interesting analysis of a song from Bob Dylan’s Music Box http://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/481/Oxford-Town So come and join us inside and listen to every version of every song composed, recorded or performed by Bob Dylan, plus all the great covers and so much more.

It seems that the line by line breakdown you are giving the song does not seem to explain the meaning of the song (as it seems to me!)

I thought the whole point was a family group were going to a demonstration or support. Therefore verse four is the point of the whole song. They go down in political support against an act of discrimination and find the whole occassion far bigger and worse than they could have imagined. They went to help but found themselves powerless – so they hope that at least someone can sort the mess out.

I would have thought that “around the bend” would refer to the tense moment when the Greyhound leaves the interstate highway and curves around (rather like our motorways) towards the target Town. It is the moment you have almost “arrived” and you have no idea what to expect. Exciting but un-nerving.

The rest of the song is about what happens there.

Amazing the it has myriad echos in the current “Black Libes Matter” demonstration all accross the USA.

I love the way Dylan plays with time in his lyrics. The song’s verses are structured present, past, past, past, present to show reflection of the events of that day and the sad outcome. I feel verse four is important in explaining the escalation of the situation. My interpretation is that this family came down to show their support to James Merideth in protest, which is their constitutional right. However, they were met with tear gas so the police violated this right. The line, “I don’t even know why we came” I feel is pretty powerful because it’s saying “I do not know why we even bother, the constitution and the law means nothing to the authorities of this town, let alone the message we came down here to support”. Again, this is just an interpretation and I think Bob Dylan’s real genius comes from the fact that he leaves things so open that they can be interpreted many different ways, yet at the same time you hear the lyrics and you know there is a a message there.

I am thinking “around the bend” is a geographic description, referring to the location of Oxford (Town) in relation to the Mississippi River. It’s another understated way of saying something…and it sets up the rhymes for the rest of the verse, for sure.