by Jochen Markhorst

PLAYBOY: Do you think you have a purpose and a mission?

PLAYBOY: Do you think you have a purpose and a mission?

BOB DYLAN: Henry Miller said it: The role of an artist is to inoculate the world with disillusionment.

Playboy interview, March 1978

They met once, Dylan and Henry Miller, but that wasn’t really a success. Dylan is with Joan Baez in Big Sur, California, in the late summer of ’63, and Baez casually mentions that Miller lives nearby. She happens to know him. The fan Dylan wants to meet him, and after the Baez concert in Los Angeles (October 12th), where Dylan makes his Hollywood Bowl debut as an opener and accompanist for Baez, she takes him and sister Mimi to the famous writer. In the liner notes of Another Side Of he incorporates an impression of that encounter:

henry miller stands on other side of ping pong table an’ keeps talkin’ about me. “did you ask the poet fellow if he wants something t’ drink” he says t’someone gettin’ all the drinks. i drop my ping pong paddle an’ look at the pool. my worst enemies don’t even put me down in such a mysterious way.

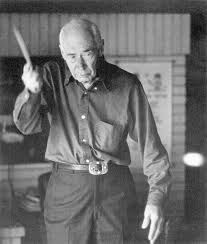

At that time, August ’64, it still seems to be a somewhat surreal memory of a fictitious encounter. But Henry Miller is indeed a fanatical ping-pong player, and in the same Playboy interview in 1978 in which he quotes the above words of Miller, it seems to be a real, true memory: “Yeah, I met him. Years ago. Played ping-pong with him,” which he repeats a year later, in the interview for L’Expresse with French journalist Philippe Adler (“we played table tennis”).

Years later, February 1975, when asked about Dylan in the Rolling Stone interview with Dylan fan Jonathan Cott, Henry Miller remembers:

“I have no way of knowing whether Bob Dylan was influenced by me. You know, Bob Dylan came to my house ten years ago. Joan Baez and her sister brought him and some friends to see me. But Dylan was snooty and arrogant. He was a kid then, of course. And he didn’t like me. He thought I was talking down to him, which I wasn’t. I was trying to be sociable. But we just couldn’t get together. But I know that he is a character, probably a genius, and I really should listen to his work. I’m full of prejudices like everybody else. My kids love him and the Beatles and all the rest.”

Dylan remains an admirer. He often mentions Miller when asked about his favourite writers, Miller drops by in Tarantula, and in 2000 that enigmatic line from the Oscar-winning “Things Have Changed” (I feel like putting her in a wheel barrow and wheeling her down the street) seems to be a paraphrase of an excerpt from Miller’s Tropic Of Capricorn: “Sometimes he’d stand her on her hands and push her around the room that way, like a wheelbarrow.”

Overlapping is the love for songs by both greats. Quantitatively less often than in Dylan’s Chronicles, of course, but in any Miller book about every four or five pages a song, a musical scene or a memory of a song comes along.

At the crossroads of both declarations of love lies John Jacob Niles. Miller writes full of admiration in Plexus (1952):

“Over the coffee and liqueurs we would sometimes listen to John Jacob Niles’ recordings. Our favorite was “I Wonder As I Wander”, sung in a clear, high-pitched voice with a quaver and a modality all his own. The metallic clang of his dulcimer never failed to produce ecstasy. He had a voice which summoned memories of Arthur, Merlin, Guinevere. There was something of the Druid in him. Like a psalmodist, he intoned his verses in an ethereal chant which the angels carried aloft to the Glory seat. When he sang of Jesus, Mary and Joseph they became living presences. A sweep of the hand and the dulcimer gave forth magical sounds which caused the stars to gleam more brightly, which peopled the hills and meadows with silvery figures and made the brooks to babble like infants.”

In every respect (content, stylistic and even word choice) comparable to Dylan in Chronicles (2004):

“I listened a lot to a John Jacob Niles record, too. Niles was nontraditional, but he sang traditional songs. A Mephistophelean character out of Carolina, he hammered away at some harplike instrument and sang in a bone chilling soprano voice. Niles was eerie and illogical, terrifically intense and gave you goosebumps. Definitely a switched-on character, almost like a sorcerer. Niles was otherworldly and his voice raged with strange incantations. I listened to Maid Freed from the Gallows and Go Away from My Window plenty of times.”

Well-chosen words, from both writers. And Dylan implicitly reveals the sources for two of his songs. “Maid Freed From The Gallows” has given him the plot for “Seven Curses” (1963), and “Go Away From My Window” leaves traces, too:

Go away from my window Go away from my door Go away way from my bedside And bother me no more

…so, the opening line, the rhyme scheme and the theme for “It Ain’t Me, Babe”.

John Jacob Niles, however, has the words spoken by the girl, the girl with whom the narrator is in love and by whom he is rejected. According to his own words, this is a true story. At least, that’s how Niles introduces the song, in 1957:

“I wrote Go Away From My Window for a girl, with blue eyes and blond hair, and the year was 1908. I was exactly sixteen years of age. The girl didn’t think much of the song, she didn’t think much of me. Since then, a great many people have sung Go Away From My Window.”

Touching. Though not very believable – it is not very likely that a sixteen-year-old boy in love would try to charm his chosen one with a song in which the woman says that the guy should get lost. And “I wrote” also could do with some nuance; the Roud Folk Song Index dates the first of a long, long line of “Go From My Window” songs 1611, and the title is even mentioned as early as 1578. With a different tenor, though; usually these are songs in which the woman tries to warn her lover, who is standing outside under the window, that her husband has come home unexpectedly – it is the first example of the intrigue ballad of the night visit.

Niles changes the plot, and Dylan eventually tilts the motive. This brings him back to the narrative of the seventeenth century “Go From My Window”, with a different, much more vicious mentality, of course, and even with the same constellation of persons:

Go melt back into the night, babe Everything inside is made of stone There’s nothing in here moving An’ anyway I’m not alone

In Dylan’s song the third party returns, present behind the back of the speaker, just like five centuries ago the party with whom the protagonist will spend the night.

“It Ain’t Me, Babe” makes a huge impression. Joan Baez loves the song and records it as early as 1964 for her album Joan Baez 5 (which also includes her cover of Niles’ “Go Away From My Window”); it becomes a year later the breakthrough hit for The Turtles, still in 1965 Johnny Cash scores a hit with it as well, with future wife June Carter; Jan & Dean; Nancy Sinatra; Peter, Paul & Mary; Bryan Ferry through Bettye LaVette in 2018… the song has been continuously covered in all echelons of the pop world for over fifty years and the end is not yet in sight.

As a catchphrase, the song title has long since penetrated into the collective cultural baggage. In lawsuits, for example. Like in New York 2003, in the case Kinkopf v. Triborough Bridge & Tunnel Authority. An insignificant dispute about whether or not tolls have been wrongly collected, on which the judge rules in writing:

“Rather than provide any documentation to support his contention such as showing that his vehicles were elsewhere at those times and places, claimant offers the Bob Dylan “It Ain’t Me, Babe” plea.”

A feminist magazine from Berkeley calls itself It Ain’t Me Babe in 1970; a writer of an erotic novel uses the title in 2014; magazine articles; episodes of TV series; titles of graphic works of art; and in 2005 a racehorse is born and is given the name It Ain’t Me Babe, the poor soul.

The biographical crime film Blow (2001, Ted Demme), starring Johnny Depp, goes one step further. George Jung (Johnny Depp) is arrested with 660 pounds of marijuana and the judge asks: how do you plead?

George: [stands] “Alright. Well, in all honesty, I don’t feel that what I’ve done is a crime. And I think it’s illogical and irresponsible for you to sentence me to prison. Because, when you think about it, what did I really do? I crossed an imaginary line with a bunch of plants. I mean, you say I’m an outlaw, you say I’m a thief, but where’s the Christmas dinner for the people on relief? Huh? You say you’re looking for someone who’s never weak but always strong, to gather flowers constantly whether you are right or wrong, someone to open each and every door, but it ain’t me, babe, huh? No, no, no, it ain’t me, babe. It ain’t me you’re looking for, babe. You follow?”

It is a brilliant, absurd monologue, which does justice to music historical cross connections; George connects Dylan’s “It Ain’t Me, Babe” with a verse from Woody Guthrie’s “Pretty Boy Floyd”, which Dylan in turn has quoted in “Song To Woody” and paraphrased in “Absolutely Sweet Marie”.

Part of the Olympic magic the song owes to contrast; the lyrics are blunt and mean, almost cynical, but set-up, composition and structure of the musical accompaniment do not match that; the introductory lines to the chorus promise a We Are The Champions-like hymn, the chorus itself is, well, jubilantly comes pretty close. “It’s not me!” the narrator cheers triumphantly.

Quite indestructible, the combination of these lyrics with this magnetic melody. Thus, almost all covers are fun, at the very least – you have to dress it up very, very corny to compromise the power of the song. The downside is: it is apparently difficult to add something. All those nice covers are actually quite interchangeable. Only radically different arrangements stand out. Not necessarily better than the original, but some of them do surprise, at any rate.

At the top of that category: the old-fashioned, glowing soul approach by Bedford Incident, a completely unknown band with a completely unknown single from May 1969 – with a magnificent harmony-intermezzo and an overflowing, irresistible arrangement. Horns, violins, four male vocalists and a complete band – fortunately, Bedford Incident completely fails in Henry Miller’s function-requirement to inoculate the world with disillusionment. Although… Bedford Incident’s single never got any further than “Best Leftfield Pick” on Radio KIBH in the remote village of Sewald, Alaska, August 1969.

Which, with all due respect for Sewald and Radio KIBH, is a bit of a disillusionment, obviously.

And in case of difficulty, here’s an alternative source…

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=frVt1jGDS6Y

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

Every kid that ever lived played wheelbarrow with their siblings or friends. No need to attribute a Dylan lyric in such a farfetched way.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/315/It-Ain't-Me,-Babe

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.