This article continues from Bob Dylan Blues part 1: a greatest hit

by Jochen Markhorst

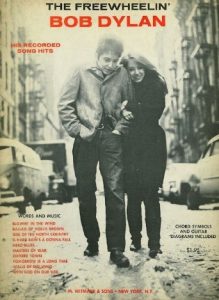

Not only on Greatest Hits, but also on Freewheelin’ “Bob Dylan’s Blues” is an odd duck. The other twelve songs are all coherent, either tell a story (“Oxford Town”, “Girl From The North Country”), or communicate in unrelated verse lines a single, text-transcending image, or a single comprehensive message (“Blowin’ In The Wind”, “Masters Of War”, “Hard Rain”). The more insignificant songs, such as “Bob Dylan’s Dream” or “Down The Highway” and even “I Shall Be Free” are still more or less coherent.

Not only on Greatest Hits, but also on Freewheelin’ “Bob Dylan’s Blues” is an odd duck. The other twelve songs are all coherent, either tell a story (“Oxford Town”, “Girl From The North Country”), or communicate in unrelated verse lines a single, text-transcending image, or a single comprehensive message (“Blowin’ In The Wind”, “Masters Of War”, “Hard Rain”). The more insignificant songs, such as “Bob Dylan’s Dream” or “Down The Highway” and even “I Shall Be Free” are still more or less coherent.

“Bob Dylan’s Blues” is the only song avoiding that. Five unrelated verses, each a short tableau of its own, which together do not form one atmosphere, not one state of mind and not one narrative – they remain five loose, uncorrelated snapshots.

The opening promises a grotesque fantasy à la “Motorpsycho Nitemare”, “I Shall Be Free No. 10” or “Highway 61 Revisited”:

Well, the Lone Ranger and Tonto They are ridin’ down the line Fixin’ ev’rybody’s troubles Ev’rybody’s ’cept mine Somebody musta tol’ ’em That I was doin’ fine

An opening stanza in a style that will become characteristic of Dylan’s lyrics in about three years’ time. The alienating effect caused by the use of cultural icons or archetypes from other art disciplines, in this case the television heroes from the Western series The Lone Ranger, is comparable to the guest appearance of Cassius Clay in “I Shall Be Free No. 10”, of Captain Arab in “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream” or of Cinderella in “Desolation Row” – to name but three of the many, many examples.

This becomes even more alienating by embedding those intruders in, as Dylan later calls it in his Nobel Prize speech, the vernacular; the blues clichés and the folk lingo, “the only vocabulary that I knew, and I used it.”

“Ridin’ down the line” is vernacular that young Dylan knows from half his baggage. From “Cocaine Blues”, for example, or from “On The Atchison, Topeka And The Santa Fe” – and above all from Woody Guthrie of course, from “Talking Sailor Blues”; the Guthrie song which in more than one respect (musically, for example) is a template for this early Dylan song;

Doorbell rung and in come a man, I signed my name, I got a telegram. Said, "If you wanna take a vacation trip, Got a dish-washin' job on a Liberty ship." Woman a-cryin', me a-flyin', out the door and down the line!

The next lines are just as recognizable. Fixin’ ev’rybody’s troubles, ev’rybody’s ‘cept mine is a variant of the well-known wailing from lamento’s like “Oh, Lonesome Me” and “But Not For Me”, and variants of I guess I’m doing fine sound familiar thanks to dozens of country and folk songs – Dylan’s trigger may be the recent country hit “Funny How Time Slips Away” (written by Willie Nelson).

The narrator of the second verse, unlike the protagonist of the opening couplet, is not troubled at all:

Oh you five and ten cent women With nothin’ in your heads I got a real gal I’m lovin’ And Lord I’ll love her till I’m dead Go away from my door and my window too Right now

This is a confident, seriously infatuated young man, and the verse is even autobiographical, as we may conclude in this exceptional case. In her memoirs A Freewheelin’ Time (2008), Suze Rotolo, Dylan’s girlfriend in those years, reveals quite a lot about the background of the songs on this LP, and she even quotes from letters Dylan wrote to her while she was in Italy:

“Some of the words he wrote in the letters became song lyrics, others he put in quotes so I would know they were from a newly written song:

I had another recording session you know—I sang six more songs—you’re in two of them — Bob Dylan’s Blues and Down The Highway (“All you five & ten cent women with nothing in your heads I got a real gal I’m loving and I’ll lover her ’til I’m dead so get away from my door and my window too—right now”). Anyway you’re in those two songs specifically—and another one too—“I’m in the Mood for You”—which is for you but I don’t mention your name…. “

And although Rotolo modestly adds a disclaimer a little later:

“I don’t like to claim any Dylan songs as having been written about me, to do so would violate the art he puts out in the world. The songs are for the listener to relate to, identify with, and interpret through his or her own experience.”

… she most certainly may, and we may, go so far as to say that this chorus, these thirty-eight words, express Dylan’s infatuation with Suze.

Stylistically still somewhat in line with the first verse. The opening is again disruptive. “Five and ten cent women” is not a household term. The five and ten cent, or five and dime is the department where the bargains are, five-and-dime products stand for “cheap”, “low quality”, and the same goes for the food you could get at the lunch counter there (like at Woolworth and at Kresge): cheap and not really refined.

In a few songs, the expression does appear, but never with the negative, insulting connotation that Dylan now attributes to it. The most famous is Bing Crosby’s “I Found a Million Dollar Baby (in a Five and Ten Cent Store)”, Glenn Miller is overjoyed with the love so sublime he finds in Woolworth’s five and dime (“A String Of Pearls”, 1944) and a derogatory connotation really only sounds in the ancient “Braggin’” (1941, Harry James and his Orchestra), which Dylan will sing on Triplicate in 2017:

Braggin' 'bout your fishin' 'Bout your horseshoe pitchin' Bet you always keep the score Braggin' 'bout your medal That's the kind they peddle Down at the five and ten cent store

But to dismiss flirtatious ladies as five and ten cents women with nothing in your heads is an original and alienating find of the young poet.

Just like in the previous verse, Dylan contrasts the unusual with the ordinary; this original insult is followed by run-of-the-mill lingo. Especially the last line, Go away from my door and my window too, is an evergreen, obviously. Dylan copies it quite verbatim from John Jacob Niles’ classic “Go Away From My Window” and will further vary on it in “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”, in “It Ain’t Me, Babe”, in “Can You Please Crawl Out Your Window”… up to Rough And Rowdy Ways, 2020, the window is one of Dylan’s favourite whereabouts for protagonists and antagonists.

The expressions five-and-ten-cents and the synonym five-and-dime are of course – literally – subject to inflation. At the end of the 70’s the first upgrades dollar shop and pound shop pop up and the previous specification becomes a metaphor like Dylan already used it in 1962: five-and-dime or nickel-and-dime is something like “worthless”, “banal”.

Until 1982, that is, when Robert Altman’s film adaptation of the successful play Come Back To The Five And Dime, Jimmy Dean, Jimmy Dean becomes a huge hit. The play, and the film, is set in a Woolworth’s Five-And-Dime in Texas, not far from Marfa, where James Dean’s last film Giant (1955) was shot. It’s 1975 and the five ladies of the James Dean fan club The Disciples Of James Dean commemorate the death of their idol, twenty years ago today.

It’s a great, suffocating actors’ movie with a particularly beautiful, poignant, melancholy ending: the sudden flash forward to the place of action years later. The Five And Dime is abandoned, dilapidated, in the dusty mirror we see the apparitions of Mona, Joanne and Sissy (Sandy Dennis, Karen Black and Cher), hollowly singing their McGuire Sisters imitation (“Sincerely”).

As an expression, five and dime has a bitter-sweet, melancholic charge since then, depicting something like the innocence of the 1950s, when we were still young and beautiful and carefree, when James Dean and Marilyn Monroe were still alive.

Incidentally, Come back to the five and dime, Jimmy Dean has a similar emotional charge, and also a similar musicality and a similar timbre as the word combination Goodbye Jimmy Reed – the song of cinephile Dylan from 2020. Just like “Bob Dylan’s Blues” a song of unrelated verses, with alienating clashes of clichés with anomalies… yet in the 2020 song, a coherent image still does emerge from all of this.

To be continued. Next up: Bob Dylan’s Blues – part III

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/4920/Goodbye-Jimmy-Reed

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.