by Jochen Markhorst

The list of Grammy Award winners reveals that 1961 was not a bad year, in Musicland. Ray Charles wins four, including for his best vocal performance single record on “Georgia On My Mind” and one for the best rhythm & blues performance, being “Let The Good Times Roll”; Ella Fitzgerald gets two for “Mack The Knife”; Cole Porter; Henry Mancini; and Marty Robbins (best country & western, “El Paso”)… names, songs and albums that have stood the test of time.

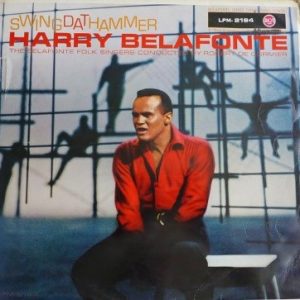

The young Dylan probably hears with appreciation who wins in the category best performance folk: Harry Belafonte, for his album Swing Dat Hammer. The King of Calypso is a common thread in Dylan’s career. In interviews he invariably mentions Belafonte – Odetta – The Kingston Trio – Woody Guthrie, in the listing of artists that put him on the track to his breakthrough as a folk artist. In the Playboy interview with Nat Hentoff (autumn ’65) even as the primal source: “First it started with, you know, Odetta. Oh no, it starts with Harry Belafonte. It starts with Harry Belafonte.”

Dylan will always be grateful to Belafonte for his first studio experience, for the invitation to play harmonica on “The Midnight Special”, for the album of the same name, in ’62. It makes an indelible impression on Dylan, although his memory of his “professional recording debut” (Chronicles, chapter 2) is not entirely correct historically – the studio recording on which Dylan “made a professional debut” is five months earlier, on Carolyn Hester’s third record (also harmonica, and quite prominent – as in “I’ll Fly Away”).

Whatever the case, Belafonte seems to make more of an impression in February ’62. In Chronicles, the autobiographer Dylan devotes many words to Belafonte. Only superlatives, roaring compliments and expressions of respect – both for Harry’s music, his acting and his personality at all. It comes close to a canonization:

“Astoundingly and as unbelievable as it might have seemed, I’d be making my professional recording debut with Harry, playing harmonica on one of his albums called Midnight Special. Strangely enough, this was the only one memorable recording date that would stand out in my mind for years to come. Even my own sessions would become lost in abstractions. With Belafonte I felt like I’d become anointed in some kind of way.”

… the words with which Dylan concludes his long declaration of love (over 400 words) to Harry Belafonte.

By the way, it leads to a moving reaction of the honestly surprised, elderly protagonist. He actually thought at the time that the monosyllabic, closed Dylan, who flatly refused to play in a second take, who threw his harmonica in the wastebasket on his way out, looked down on him and his music:

“I remember thinking, does he have that much disdain for what I’m doing? But I found out later that he bought his harps at the Woolworth drugstore. They were cheap ones, and once he’d gotten them wet and really played through them as hard as he did, they were finished. It wasn’t until decades later, when he wrote his book (Chronicles), that I read what he really felt about me, and I tell you, I got very, very choked up. I had admired him all along, and no matter what he did or said, I was just a stone, stone fan.”

(interview in Mojo, July 2010, with the then 83-year-old Belafonte)

Traces of Belafonte can be found throughout Dylan’s oeuvre. In song fragments (in “If You Ever Go To Houston”, 2009, for example), in choice of repertoire (“Dink’s Song”, “Rocks And Gravel”, “Delia’s Gone”, “Go Away From My Window”… Belafonte has recorded dozens of songs that inspired Dylan, or at least stimulated), in references (in “Desolation Row”), and it is not inconceivable that Dylan derives the title for his literary debut, Tarantula, from Belafonte’s signature song “The Banana Boat Song (Day-O)”:

A beautiful bunch o' ripe banana Daylight come and me wan' go home Hide the deadly black tarantula Daylight come and me wan' go home

In No Direction Home Belafonte can also be heard, with his interpretation of “Bald-Headed Woman”, one of the chain-gang songs, songs sung by the working, chained prisoners, from this award-winning album Swing Dat Hammer. On that record Dylan also notices “Rocks And Gravel”, which he will record in April ’62 during the second Freewheelin’ session, and especially Belafonte’s version of the chain-gang song “Diamond Joe”:

Ain't gonna work in the country And neither on Forester's farm I'm gonna stay 'till my Marybell come She gone call me Tom

There are two songs called “Diamond Joe”. One is the nineteenth century cowboy song Dylan will be covering on Good As I Been To You in 1992. That one has nothing in common with the other, which is the song Dylan will perform, in a variation, as Jack Fate in the film Masked & Anonymous (2003). The oldest recording of this “Diamond Joe” is from 1927, by the Georgia Crackers. But Belafonte uses as source the recording made by the legendary music archivist Alan Lomax in 1937 at the infamous Parchman Farm, the Mississippi State Penitentiary. The arrangement and interpretation by the Calypso king are breath-taking, by the way.

As a radio maker Dylan plays both songs in Theme Time Radio Hour episode 73 (March 2008, “Joe”) – Cisco Houston’s version of the cowboy song, and the steaming 1927 Georgia Crackers recording of the other (“No matter how you slice it, that’s rock and roll”, Dylan mumbles approvingly).

For the inspiration of “Maggie’s Farm” Dylan circles often refer to “Down On Penny’s Farm” (The Bently Boys, 1929, alternative title “Hard Times In The Country”). That song unmistakably provides the template for Dylan’s “Hard Times in New York City”, both lyrically and musically, but the resemblance to “Maggie’s Farm” is really not much more than “some girl’s name + farm”. No, the “Diamond Joe” by Belafonte (or rather: by Charlie Butler, the singing prisoner on the original Lomax recording) is a more obvious candidate.

Not too important, of course. More importance has the landslide impact of the song. In 1965, “Maggie’s Farm” is the cat thrown amongst the hard-core folk pigeons – Dylan opens his much-discussed electric set at the Newport Folk Festival with the song, and things would never be the same. Retrospective historiography says that the public’s dismay had more to do with the lousy, overdriven sound quality than with the so-called taboo-breaking electrical amplification, but the myth is inextinguishable. As are the stories around it. About Pete Seeger is still told, mainly thanks to fantasist Greil Marcus, how he attacked the cables with an axe. But Seeger himself later states, and credibly: “I only went to the sound engineer to tell him that Dylan’s microphone needed adjusting.” In his memoirs he is unequivocal:

“Bob was singing Maggie’s Farm, one of his best songs, but you couldn’t understand a word, because of the distortion.”

The folk legend continues to admire Dylan publicly and continues to play Dylan songs after Newport, until his death in January 2014. Not “Maggie’s Farm” though. He allows that one to pass him by, as Ketch Secor, the foreman of Old Crown Medicine Show, tells in a heartwarming necrological article for The New Yorker (“Pete Seeger Gazing up into the Trees”, 27 February 2014):

“In 2005, the Clearwater Festival went on in spite of a cold, driving rain. My band, Old Crow Medicine Show, played our set, then cheered from the side stage while Pete Seeger sang with a chorus of schoolchildren. Later that day, I joined in with Pete’s grandson, Tao Rodriguez-Seeger, and his rock band. Backstage, Pete crunched on an apple and looked up at the dripping trees, seemingly unaware of the clash of drums and guitars. While Tao and I sang “Maggie’s Farm,” I kept looking back to see how Pete liked it, but he just went on munching that apple and gazing up into the trees.”

Half-brother Mike Seeger does the honours and records in 1999 with David Grisham and John Hartford the album Retrograss, containing a beautiful rocking chair version of “Maggie’s Farm” in an archaic, Dock Boggs-like arrangement.

Pete’s last professional recording – and only time in his entire life that he makes a music video – is Dylan’s “Forever Young” (Seeger’s contribution to the Amnesty project Chimes Of Freedom, 2012). Irresistible – just like the Caribbean cover of “Forever Young” by that other eternally young giant, Harry Belafonte (1981), by the way.

To be continued. Next up: Maggie’s Farm – part II

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 7000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood