by Jochen Markhorst

The story so far…

- Highway 61 Revisited (1965) part I: Look out kid

- Highway 61 Revisited (1965) part II: On a desert island

- Highway 61 Revisited (1965) part III: Words don’t interfere

1 Open your ears; 9r”5j5&

But O O O O that Shakespeherian Rag— It’s so elegant So intelligent

(T.S. Eliot – The Waste Land)

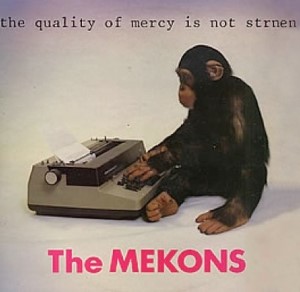

In 2020 The Mekons still exist, the British-American crew from Leeds who initially created a furore as a hard, chaotic punk rock band, but has now explored just about every corner of the music world. Title plus cover of their 1979 debut album is still one of the witty highlights: The Quality Of Mercy Is Not Strnen. The cover photo, a monkey with a typewriter, clarifies the title: this chimp almost typed a Shakespeare quote (“The quality of mercy is not strained,” from The Merchant Of Venice).

In 2020 The Mekons still exist, the British-American crew from Leeds who initially created a furore as a hard, chaotic punk rock band, but has now explored just about every corner of the music world. Title plus cover of their 1979 debut album is still one of the witty highlights: The Quality Of Mercy Is Not Strnen. The cover photo, a monkey with a typewriter, clarifies the title: this chimp almost typed a Shakespeare quote (“The quality of mercy is not strained,” from The Merchant Of Venice).

The joke is, of course, based on the Infinite Monkey Theorem, which states – in variants – that an immortal monkey with infinite time one day will type the Collected Works of Shakespeare. Variants talk about a million monkeys and a million years, or an infinite number of monkeys and the typing of Hamlet, but Shakespeare is a constant in all these variants.

It’s a brilliant thesis to motivate students of the probability theory – strongly visual, humorous and fairly sharply defined (Hamlet has 30,577 words, about 130,000 letters). But solution and evidence are sobering. The odds are so small that it cannot be described in our language. If every proton in the universe from the Big Bang to the end of the universe were a typing monkey, billions more universes would be needed before we would have a 1 in a trillion chance of a flawless Hamlet.

That does not scare off. Throughout every decade, there are scientists who manage to free up a scholarship to experiment with the thesis. In 2002, students and lecturers at the University of Plymouth put six crested macaques to work for a month. The result is meagre: only five pages of text, mainly filled with the letter s. At most, the very last line is somewhat exciting still:

blbbbbnnfllmnnmjfgmnmmmassssssjjkbhnmnn

Despite this disappointment, the work is published in a fine hard-cover edition with photographs of the authors: Notes Towards The Complete Works Of Shakespeare, by Elmo, Gum, Heather, Holly, Mistletoe & Rowan, Sulawesi Crested Macaques (Macaca nigra) from Paignton Zoo Environmental Park (UK).

More successful are automated simulation programmes. In August 2003 a virtual monkey in Scottsdale, Arizona, after billions and billions of “monkey years” produces nineteen letters from The Two Gentlemen Of Verona (“VALENTINE. Cease toIdor:eFLP0FRjWK78aXzVOwm)-‘;8.t”), other teams achieve similar successes with Richard II and Timon Of Athens, and the preliminary record is set on a website, The Monkey Shakespeare Simulator, with 24 letters from Henry IV: “RUMOUR. Open your ears; 9r”5j5&?OWTY Z0d” (likewise after billions of virtual monkey years).

2 A cloud that’s dragonish

“Shakespeare-dropping” is a motif in Dylan’s oeuvre. Sometimes unveiled, such as Ophelia and Romeo in “Desolation Row”, Othello and Desdemona in “Po’ Boy” and Romeo and Juliet in “Floater”. Sometimes with a traceable quote, like in “Mississippi” (“Give me your hand and say you’ll be mine” from Measure For Measure) and Hamlet’s “to be or not to be” in “My Own Version Of You”, and occasionally with a loud and clear hello, like in “Stuck Inside Of Mobile” (“Shakespeare’s in the alley”). Examples from 1965 to 2020 – the bard from Stratford-upon-Avon has been receiving tips of the hat from the Hibbing bard for over fifty years.

Beyond that begins the grey zone, the zone in which the dozens of disputable Shakespeare references float around, text fragments that, depending on your tolerance limit, are eligible to apply for the “Shakespeare reference”-stamp.

In “You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome” Dylan sings dragon clouds, Shakespeare’s Antony says in Antony And Cleopatra: “Sometimes we see a cloud that’s dragonish”. The Earl of Warwick in Henry VI says: “Where having nothing, nothing can he lose” – which could be celebrated by more fanatical reference seekers as the source for “Like A Rolling Stone” (when you got nothing, you got nothing to lose). The album title Time Out Of Mind might be a quote (Romeo And Juliet, Act I, sc. 4) and album title Tempest happens to be a Shakespeare title as well (all right, factually The Tempest).

Which brings us into the light grey zone: paraphrases and “inspirations’, again depending on your willingness or eagerness to see a paraphrase or a reference in it.

An exceptional suicide like to eat fire (from “Too Much Of Nothing”) can only be found once in all world literature (in Julius Caesar) and in the same Basement song, whose title echoes Much Ado About Nothing, we hear another unique expression (to abuse a king, only to be found in Shakespeare’s Pericles) plus some remarkable jargon like “oblivion”, “temper”, “mock” – words Dylan never uses elsewhere, but can be found in Shakespeare’s Collected Works by the dozen. And another Basement song (“Tears Of Rage”) offers similar possibilities of comparison with King Lear.

But by now we are leaving even the light grey zone, and we are approaching the Infinitely Typing Monkeys. After all, album titles such as Desire and Saved, for example, are also words that can be found in Shakespeare’s sonnets and tragedies – but can hardly be considered references. Even an enthusiastic Dylan researcher like Professor Ricks would agree. But that same Professor Ricks is the leader of the faction of Dylanologists who enthusiastically promote unspectacular word correspondences and vaguely similar phrases to possible Shakespeare references – correspondences and similarities that would be classified by the scientists at the University of Plymouth under: “hits by the Infinitely Typing Monkey Dylan”.

A maverick then is the word combination twelfth + night from “Highway 61 Revisited”.

3 If music be the food of love, play on

Now the fifth daughter on the twelfth night Told the first father that things weren’t right My complexion she said is much too white He said come here and step into the light he says hmm you’re right Let me tell the second mother this has been done But the second mother was with the seventh son And they were both out on Highway 61

Mick Fleetwood is not secretive, in his entertaining memoirs. One of Fleetwood Mac’s older albums is named after it (the underrated Then Play On, 1969 – “Oh Well” is on the American reissue) and he also calls his autobiography Play On; Now, Then And Fleetwood Mac (2014). Why, he explains right away in the first paragraph:

“Play on. Two words, no more, but they’ve said it all to me.

They’ve been, at different times, a simple direct order, a call to action, a mantra and a comforting concept that promised rebirth. I first read them in the most beautiful and romantic couplet in Twelfth Night, my favourite of Shakespeare’s works. I’ve never forgotten it; in fact I took it to heart

immediately because it spoke to me.”

He has signed with “Play On” half his life, has a tendency to encourage people around him with these very words and Then Play On “I still count as my favourite record”.

It’s a legacy of his youth; happy he was not, in the boarding schools in Gloucestershire, but thanks to this British part of his upbringing the young Fleetwood is affected by Duke Orsino’s monologue:

If music be the food of love, play on; Give me excess of it, that, surfeiting, The appetite may sicken, and so die. That strain again! it had a dying fall: O, it came o'er my ear like the sweet sound, That breathes upon a bank of violets, Stealing and giving odour!

… and at the same time, Mick’s declaration of love demonstrates the difference with Dylan’s use of Shakespeare: to Fleetwood, it is rhyme and reason.

Dylan of course knows the title of Shakespeare’s romantic comedy. And by now (1965) he knows the urge of many followers and journalists to dig for and find far-fetched allusions and produce insane interpretations of his lyrics. It’s the mid-sixties Dylan, so the subtlest tinge of maliciousness is enough to then play on: to liven up the quasi-Biblical enumeration of fifth daughter, first father and second mother with a twelfth night.

It’s a direct hit; among the reference seekers, this contextless Twelfth Night is still high up on the told-you-so-list, the list of references to prove how much Dylan has been influenced by Shakespeare. It’s not too convincing, though; the quotes and paraphrases never really transcend name-dropping, are mostly rhyme and never reason. Sure, Dylan’s admiration for Shakespeare is sincere and respectful, which he repeatedly confesses in interviews, such as in the Uncut interview, 2015:

“You travel the world, you go see different things. I like to see Shakespeare plays, so I’ll go — I mean, even if it’s in a different language. I don’t care, I just like Shakespeare, you know. I’ve seen Othello and Hamlet and Merchant of Venice over the years, and some versions are better than others. Way better. It’s like hearing a bad version of a song. But then somewhere else somebody has a great version.”

… but a demonstrable influence on the style of his lyrics, as the Beat Poets have, or a demonstrable artistic soul affinity, as with Kafka or Rimbaud, or even appropriations to poetically convey a story, as from Ovid or Junichi Saga – no. Dylan’s Shakespeare references are actually little more than glitter and gold dust. Like the otherwise empty twelfth night here. Which Dylan, unconsciously associating or consciously scattering glitter, amplifies some more with the subsequent, Shakespearian complexion. Shakespeare uses this word more than fifty times (three times in Twelfth Night, by the way). The only other time in his entire oeuvre that Dylan uses the word is in yet another Shakespeare reference, the one in “Floater” (2001):

Romeo, he said to Juliet, “You got a poor complexion. It doesn’t give your appearance a very youthful touch!” Juliet said back to Romeo, “Why don’t you just shove off If it bothers you so much.”

… in which the use of the names Romeo and Juliet again has no function whatsoever – except as a Brechtian “V-Effekt” (Verfremdungseffekt, alienation effect) – the same function as Mack The Finger, God and Georgia Sam in “Highway 61 Revisited”.

In short, Dylan’s Shakespeare love is real, but is limited to shimmering on the surface. Or, as the Supreme Bard would say, “Love is a smoke raised with the fume of sighs”. (Romeo And Juliet, Act I, sc. 1)

To be continued. Next up: Highway 61 Revisited – part V

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

You’ll find some notes about our latest posts arranged by themes and subjects on the home page of this site. You can also see details of our main sections on this site at the top of this page under the picture. Not every index is complete but I do my best. Tony Attwood

On one of his time-travelling excursions, Dylan sings to Shakespeare the lines “My warehouse eyes, my Arabian drums/Should I put them at your gate?”; when the playwright later pens ‘Twelfth Night”, the lines “Make me a willow cabin by your gate/And call upon my soul within the house” appear in Act 1, sc 5 .

A co-incidence?….Me thinks not!