by Jochen Markhorst

At the beginning of December ’67 it starts to itch, with The Band (which doesn’t have a name at that time – but in the village, in Woodstock, the boys are always called the band). Dylan has been away three times in the past six weeks. To Nashville, to record John Wesley Harding in three shifts. In the meantime, the men, now with Levon Helm, have merrily continued playing. Levon remembers:

At the beginning of December ’67 it starts to itch, with The Band (which doesn’t have a name at that time – but in the village, in Woodstock, the boys are always called the band). Dylan has been away three times in the past six weeks. To Nashville, to record John Wesley Harding in three shifts. In the meantime, the men, now with Levon Helm, have merrily continued playing. Levon remembers:

“When I reported for duty in the basement the day after I arrived in Woodstock, they were working on “Yazoo Street Scandal.” Richard was playing drums. (…) I was uptight about playing, because I’d been away from it for so long, but soon they had me working so hard, there wasn’t anything else to do. Richard was writing and singing up a storm. We cut his “Orange Juice Blues” (also called “Blues for Breakfast”), with Garth playing some honky-tonk tenor sax. Richard sang and co-wrote (with Robbie) “Katie’s Been Gone,” and Garth overlayed some organ. Rick and Robbie did a great song called “Bessie Smith.”

(This Wheel’s On Fire, Levon Helm, 1993)

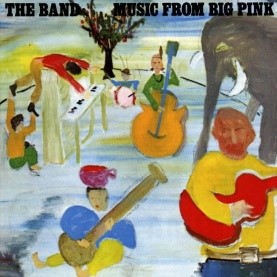

Robbie Robertson expresses the creative explosion in a similar way. They decline Dylan’s offer to play on the album, but are happy to accept his painting for the cover (which includes the elephant, five musicians and a sixth character supporting the pianist), and it’s also pretty clear that they want the Dylan song “I Shall Be Released” and both co-productions “Tears of Rage” and “This Wheel’s on Fire” on the album, despite the abundance of their own songs to choose from:

“Rick felt quite strongly about “Caledonia Mission” and wanted to give that a go. We all agreed. I definitely thought “Yazoo Street Scandal” was right up Levon’s alley. (…) I wrote “The Weight,” which was also becoming a contender. “Chest Fever” too, with its crazy “basement” words, and Garth’s new “Toccata and Fugue in D Minor” intro, borrowed from Bach. We had to choose between “Lonesome Suzie” and “Katie’s Been Gone.” Both had Richard’s sympathetic sentiments. I liked that “Katie’s Been Gone” had no intro and that Rick’s harmony in the ending had a touch of Pet Sounds influence, but “Lonesome Suzie” was so moving. I suggested we let John Simon decide.”

And Richard Manuel’s anecdote about the genesis of “Tears Of Rage” illustrates with what ease and how quickly, off the cuff, all those beautiful songs from the masterpiece Music From The Big Pink came into being:

“He came down to the basement with a piece of typewritten paper … and it was typed out … in line form … and he just said “Have you got any music for this?” I had a couple of musical movements that fit, that seemed to fit, so I just elaborated a little bit, because I wasn’t sure what the lyrics meant. I couldn’t run upstairs and say, “What’s this mean, Bob?” “Now the heart is filled with gold, as if it was a purse.”

(Conversations with the Band, The Woodstock Times, 1985)

… virtually the same lightning process as that other masterful co-production from the Basement, in “This Wheel’s On Fire”, about which Rick Danko says in the same interview series in The Woodstock Times:

“We put together about 150 songs at Big Pink. We would come together every day and work and Dylan would come over. He gave me the typewritten lyrics to “Wheels on Fire.” At that time, I was teaching myself to play the piano. Some music I had written on the piano the day before just seemed to fit with Dylan’s lyrics. I worked on the phrasing and the melody. Then Dylan and I wrote the chorus together.”

Technically, we owe the Basement Tapes to Garth Hudson, who has been conscientious from day one about recording and archiving those around 150 songs.

He’s the best musician in The Band, and also the taciturn one. At least, he rarely gives interviews, and in those few interviews he gives, he doesn’t let himself be tempted to look back too deeply into the past – Garth talks with music, period. He thinks “Yazoo Street Scandal” is one of the best songs Robbie Robertson has written, and in he admires his skilfulness “with the legal pad and pencil”.

And in the same interview with Mark T. Gould for Sound Waves Magazine, November 2001, he mentions Dylan’s influence, but on a surprising level:

“He gave me the greatest lessons I ever learned about how to work in a studio. He would go in with us, play a new song only partway through, we wouldn’t much rehearse or much less play it all the way through to learn it, and he’d turn on the tape, and we’d get it down in a first or a second take.”

But then it’s 2012. Hudson helps a Canadian friend, the archivist and producer Jan Haust, who is already preparing for The Basement Tapes Complete, listens to all those tapes, selects what has survived and can still be listened to in terms of sound quality, and Garth is willing to reminisce a little more about that special summer of 1967 – for the first time in forty-five years. Mumbling, hesitating and not always coherent he does his story for the documentary Down In The Flood by Prism Films. In it he is the only band member who clearly, in so many words, recognizes Dylan as the architect of The Band, calls him a master craftsman and an educator, a teacher, and tells:

“He would sit at the coffee table, on an old Olivetti I think it was, and type out a song and we’d go downstairs, in the basement, and record it. And we watched this happen. He worked also with Richard and Rick on lyrics. I think he saw that we were all songwriters to some extent and he would show us a talent that… he was sure of what he could do, and I don’t know how many songwriters do this, but he would make a song up on the spot. Very quickly.”

And the men are good students. All the songs of Music From The Big Pink and part of the successor The Band (“The Brown Album“) are written in Woodstock – two undisputed pop monuments.

The prize song for Music From The Big Pink is “The Weight”. That is a great song, which understandably has a position on the various lists of “Hundred Best Songs All Time”, “Most Beautiful Songs From The Twentieth Century” or whatever those senseless and always fun elections are called.

But it’s one of the nails on The Band’s coffin as well. Halfway through the 70’s, a separation arises between especially Robbie Robertson and the rest of The Band, and that has a lot to do with dissatisfaction – the dissatisfaction that Robbie puts a bit too generous royalties on his own name, copyrights on songs to which the other band members feel to have contributed as well. “The Weight” is an example thereof.

To be continued. Next up: Part II – Our fearless leader

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

Untold Dylan: who we are what we do

Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. It is simply a forum for those interested in the work of the most famous, influential and recognised popular musician and poet of our era, to read about, listen to and express their thoughts on, his lyrics and music.

We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Sadly no one gets paid, but if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8000 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down