I: No colours anymore

Mick Jagger is a fan. In her memoirs (Faithfull; An Autobiography, 1994) Marianne Faithfull tells about her copy of The Basement Tapes: “I drove Mick crazy playing it over and over again,” but Jagger has been making it clear in various ways for almost sixty years now that he is and remains an admirer. Quite outspoken, even. When Mick Jagger is a guest on a Dutch talk show in 2001, the renowned interviewer Sonja Barend tries to make a point of his age in a cumbersome way. Laboriously searching for words, she stumbles over a series of half sentences that eventually lead her to some kind of a question: whether Jagger isn’t afraid that he will come across pathetic when he is sixty (he is 57 now), jumping and running over a stage. Miss Barend also seems to sense that this is becoming somewhat awkward, but Sir Michael Philip Jagger is every inch a gentleman and accordingly answers elegantly:

Mick Jagger is a fan. In her memoirs (Faithfull; An Autobiography, 1994) Marianne Faithfull tells about her copy of The Basement Tapes: “I drove Mick crazy playing it over and over again,” but Jagger has been making it clear in various ways for almost sixty years now that he is and remains an admirer. Quite outspoken, even. When Mick Jagger is a guest on a Dutch talk show in 2001, the renowned interviewer Sonja Barend tries to make a point of his age in a cumbersome way. Laboriously searching for words, she stumbles over a series of half sentences that eventually lead her to some kind of a question: whether Jagger isn’t afraid that he will come across pathetic when he is sixty (he is 57 now), jumping and running over a stage. Miss Barend also seems to sense that this is becoming somewhat awkward, but Sir Michael Philip Jagger is every inch a gentleman and accordingly answers elegantly:

Jagger: Do you like Bob Dylan?

Barend: Yes, I do like Bob Dylan…

Jagger: Well, he is over sixty and I quite like watching his shows. I think it’s quite fun and I enjoy watching him performing.

Barend: Yes, I enjoy watching him, but his voice is…

Jagger: You don’t like his voice? It’s a funny voice. It’s like… it’s a voice that’s never been one of the great tenors of our time…

Barend: No… [audience laughter, Jagger smiling patiently]

Jagger: … but it’s got a timbre, it’s got a projection and it’s got a feeling. And you were talking earlier about getting older… you know as you get older, your voice takes on a certain different resonance and a different pitch… so, there’s something to be said for that.

It is not a one-off outpouring. Throughout all the decades Jagger confesses his admiration. In 2012 he posts on his Facebook page Bob Bonis’ photo Mick Jagger with Bob Dylan album, Savannah, Georgia, May 1965 #1 (the album being Bringing It All Back Home, obviously), at the memorial service for his partner L’Wren Scott he sings “Just Like A Woman” and when interviewers start talking about the assumed depths or the poetic beauty of his own lyrics, Jagger almost always brushes it off by pointing out the quality difference with Dylan. As in the Rolling Stone interview with Jonathan Cott, in 1968:

What about people who see your songs as political or sociological statements?

Well it’s interesting, but it’s just the Rolling Stones sort of rambling on about what they feel.

But no other group seems to do that.

They do, lots of groups.

What other group ever wrote a song like “19th Nervous Breakdown,” or “Mother’s Little Helper”?

Well, Bob Dylan.

That’s not really the same thing.

Dylan once said, “I could have written ‘Satisfaction’ but you couldn’t have written ‘Tambourine Man.’”

He said that to you?

No, to Keith.

What did he mean? He wasn’t putting you down was he?

Oh yeah, of course he was. But that was just funny, it was great. That’s what he’s like. It’s true but I’d like to hear Bob Dylan sing “I Can’t Get No Satisfaction.”

Dylan’s influence on Mick’s lyrics is fairly obvious on Between The Buttons (1967). And on the overall feel as well; “She Smiled Sweetly”, incidentally the first Stones song without a guitar, is in a few ways a “Just Like A Woman 2.0” – the mercury organ sound, Jagger’s way of singing, the waltz tempo and the atypical lyrics, with Dylan echo’s like

There's nothing in why or when There's no use trying, you're here Begging again, and over again That's what she said so softly I understood for once in my life And feeling good most all of the time

That Highway 61 Revisited and Blonde On Blonde have been on Jagger’s turntable a lot is even clearer in the most Dylanesque song in the Stones catalogue, in one of the other highlights of the underrated Between The Buttons, in “Who’s Been Sleeping Here?”:

Don't you look like, like a Goldilocks There must be somewhere, somewhere you can stop Yes there's the noseless old newsboy the old British brigadier But you'll tell me now, who's been sleeping here

… a fairy tale reference, a hallucinatory procession of Dylanesque archetypes like an “old British brigadier” and a “noseless old newspaper boy”. Elsewhere in the song “a laughing cavalier”, “the three musketeers” and “cruel old grenadiers” pop up, Brian Jones plays his utmost Dylanish harmonica, couplets ending with a recurring verse line … it’s a great, folk rocking Dylan song, larded with vile Stones rock and some psychedelia.

But the album Jagger so impressed is admiring, on that beautiful pool photo in Savannah, provides the inspiration for one of the greatest Stones songs ever, for “Paint It Black” (Jagger prefers writing it without a comma);

I see a red door and I want it painted black No colours anymore, I want them to turn black I see the girls walk by dressed in their summer clothes I have to turn my head until my darkness goes

… words that may already be bubbling up as Sir Mick is listening to “She Belongs To Me” by the poolside, listening to

She’s got everything she needs She’s an artist, she don’t look back She can take the dark out of the nighttime And paint the daytime black

Jagger doesn’t call himself a poet, and he may always quickly be pointing to Dylan, but meanwhile, he does deliver superb, poetic hits. The interviewer complimenting “19th Nervous Breakdown” does have a point;

You're the kind of person you meet at certain dismal, dull affairs Center of a crowd, talking much too loud, running up and down the stairs Well, it seems to me that you have seen too much in too few years And though you've tried you just can't hide your eyes are edged with tears

… is, of course, thematically a “Like A Rolling Stone” decoction, and indeed written shortly after its release, but apart from that a beautiful, well-nigh literary quatrain, which – like Dylan so often does – conceals by its layout that a classical, medieval template is the basis. In this case this quatrain is “actually” a sestain with an aabccb-rhyme scheme:

You're the kind of person you meet at certain dismal, dull affairs Center of a crowd, talking much too loud, running up and down the stairs

… a “restructuring” which can be applied to each verse of “19th Nervous Breakdown”. The song actually has the same rhyme scheme as Dylan’s “She’s You Lover Now” and (later) “No Time To Think” and “Where Are You Tonight?”, and, moreover, the same scheme as one of the absolute highlights of French literary history, Paul Verlaine’s brilliant masterpiece Chanson d’automne (1865).

Which is not to say that Jagger deliberately copied this template or made a study of French classical poetry, but it at least shows that – despite himself – he is a poet, an artist who at least has an intuitive sense of rhyme, rhythm and reason. “I watched in glee as your Kings and Queens fought for ten decades for the gods they made” is a delightful, flowing, extremely musical and frightening verse (from “Sympathy For The Devil”). The fact that Jagger not only points to Dylan when mentioning “19th Nervous Breakdown”, but also in relation to “Mother’s Little Helper”, is understandable too:

"Kids are different today" I hear ev'ry mother say Mother needs something today to calm her down And though she's not really ill There's a little yellow pill She goes running for the shelter of a mother's little helper And it helps her on her way, gets her through her busy day

… the mockery and sarcasm of the best of Dylan’s mid-60s work, like Dylan’s best songs conveyed in superior rhyme, rhythm and reason.

And in this “Paint It Black” a fine verse like I wanna see the sun blotted out from the sky does have a highly visual, apocalyptic, Dylan-worthy quality in terms of content as well – the Glimmer Twin should be proud.

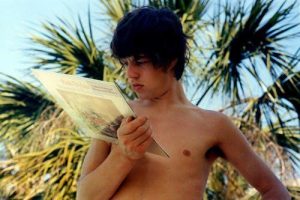

“i am called a songwriter,” the heartbreakingly young Rolling Stone reads, as he studies the Bringing It All Back Home’s liner notes, in Savannah, May 1965, “a poem is a naked person … some people say that i am a poet.”

————–

To be continued. Next up: She Belongs To Me part II: Images which have got to come out

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece