by Jochen Markhorst

“He saw right from his side and I saw right from mine, and we wore each other down for it.”

“He saw right from his side and I saw right from mine, and we wore each other down for it.”

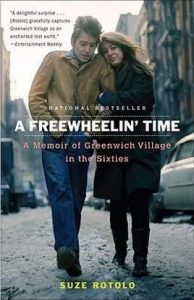

Suze Rotolo opens the chapter “Breaking Fame”, the chapter from her autobiography A Freewheelin’ Time (2008) that tells the end of her relationship with Dylan, not coincidentally with a paraphrase of a verse from “One Too Many Mornings”.

Rotolo does add a disclaimer;

“I don’t like to claim any Dylan songs as having been written about me, to do so would violate the art he puts out in the world. The songs are for the listener to relate to, identify with, and interpret through his or her own experience,”

… but indirectly, with this paraphrase, she does claim to be a muse, or at least a source of inspiration. To which she has every right, of course. Dylan is a young, receptive guy, and no man is an island – the experiences with Suze are, of course, part of what he tries to capture poetically, part of what goes on around here sometimes, tho I don’t understand too well myself what’s really happening, as he will say in the liner notes of Bringing It All Back Home (1965).

From the quartet farewell songs that for convenience we will call the Suze cycle (next to “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right”, “Girl Of The North Country” and “Boots Of Spanish Leather”, all with the same chord progression and all fingerpicking, by the way), “One Too Many Mornings” is the most intimate, perhaps the most mature and in any case the most poetic. In “Don’t Think Twice”, Dylan sometimes still does sound quite adolescently wronged, and “Girl Of The North Country” and “Spanish Leather” have an admittedly classic, but also a somewhat archaic and therefore impersonal beauty. In “One Too Many Mornings”, however, we are close to the narrator, who does not wave at his beloved in the far North or in the mountains of Madrid, but looks back at her here and now, from this threshold.

The opening is the opening of a film noir;

Down the street the dogs are barkin’ And the day is a-gettin’ dark As the night comes in a-fallin’ The dogs’ll lose their bark An’ the silent night will shatter From the sounds inside my mind For I’m one too many mornings And a thousand miles behind

… but it is a film noir for which Baudelaire has written the screenplay. We know that in these years Dylan gets to know and admires the work of the French symbolist – here echoes seem to resound from the small, posthumously published collection of “prose-poems” Le Spleen de Paris (1869), and in particular from the poem “À une heure du matin” (At One O’Clock In The Morning). The setting, from the opening lines of Baudelaire’s poem, is already very similar;

“Not a sound to be heard but the rumbling of some belated and decrepit cabs. For a few hours we shall have silence, if not repose.”

… and Dylan seems to be taking the final words to heart:

“I would gladly redeem myself and elate myself a little in the silence and solitude of night. Souls of those I have loved, souls of those I have sung, strengthen me, support me, rid me of lies and the corrupting vapours of the world; and you, O Lord God, grant me the grace to produce a few good verses, which shall prove to myself that I am not the lowest of men, that I am not inferior to those whom I despise.”

“Grant me the grace to produce a few good verses, which shall prove to myself that I am not the lowest of men…” Words the biographically interpreting Dylanologist can effortlessly lay over Dylan’s biography; Dylan has been messing around with Joan Baez for a while, Suze has to find out in an embarrassing way and he (presumably) writes this song when he spends another few weeks at Baez’s in California. Some gnawing at his conscience is not unthinkable – none of this is too graceful. Baudelaire’s need to produce those soul-cleansing verses is palpable, and the young bard undeniably succeeds. Baudelairian brilliant is already the silent night will shatter from the sounds inside my mind, but that is certainly not the only highlight:

From the crossroads of my doorstep My eyes they start to fade As I turn my head back to the room Where my love and I have laid An’ I gaze back to the street The sidewalk and the sign And I’m one too many mornings An’ a thousand miles behind

The warmth of the bed that has just been used can still be sensed, sultry is the silence of the falling night… I have to get out of here. Yet another morning here, with just the two of us, no… we’ve reached the end of the line.

It is perhaps one of the most beautiful stanzas in Dylan’s rich oeuvre. The doorstep is a crossroads, a literal and figurative threshold to a new path in life, the protagonist’s torment is visible. He looks back again, with fading eyes, at the bed, and then back to the street and the sign, still calling her “my love” in his mind… elegant. But not very honest, the decoding biographical interpreter will add. Which is completely unimportant, as the deceived one, Suze Rotolo, points out too. After all, “the songs are for the listener to relate to, identify with.” And her other point is even more worthy. Narrowing poetry to something as banal as a coded account of a real love affair “would violate the art he puts out in the world”.

The template for elegance seems to have been handed to Dylan not only by Baudelaire, but also by the sympathetic Rotolo.

Biographical, Baudelairian or realistic fiction – “One Too Many Mornings” is in any which way a masterpiece – and as a work of art it is, obviously, independent of the artist’s possible dubious impulses or presumed petty motives. The evocative power of the cinematic images and the lyrical finds are brilliant, and the irresistible recurring verse line, one too many mornings and a thousand miles behind, has the beauty of classical poetry and the familiarity of an old saying.

Nevertheless, Dylan holds back on this song for a long time. Perhaps because of the emotional charge, or maybe because the chord scheme and parts of the melody are very similar to the title track of the LP. Only in the last instance he decides to put it on The Times They Are A-Changin’ (the song is not on a first test pressing), then ignoring the song for his Carnegie performance and still in 1965 he only plays it once (in England, for a BBC television recording). It is only in 1966, then still in a drastically roughened version, that the song finds a permanent place on the set list. After that, Dylan gradually seems to recognise the indestructible beauty.

Initially, however, in ’66, he rather ostentatiously dissociates music and text. In the electric arrangement “One Too Many Mornings” is a sister of “Like A Rolling Stone”: exciting, compelling and sharp – and therefore absolutely not in keeping with the content of the lyrics. Rick Danko’s vocal contribution is illustrative; after every …and a thousand miles Dylan keeps shut for four beats, giving the delayed …behind! by Danko an almost jubilant, ecstatic emphasis. Musically absolutely a goosebumps-inducing moment, but lyrically not really a direct hit; to sing the word behind a few seconds behind the last line has a slightly too strong pun intended character. On the other hand: the beautiful version from the Basement Tapes (1967) proves that in those years The Band and Dylan really do know what the words say, but apparently, they reserve melancholy for the seclusion of the Big Pink.

The sessions in ’69 with Johnny Cash suffer from the same flaw; the words seem stripped of all meaning and at best function as a sound contribution – nothing more. A studio recording in New York, May 1, 1970, proves that Dylan can no longer let go of the song, though. And that he is still searching for a form to do justice to the power. It doesn’t quite work out yet: this time, the country rock arrangement drives the song towards a somewhat dutiful conviviality – and the harmonious ensemble singing is beautiful, but once again negates the poetry. In 1976 we are almost there. Electric, still, but the melancholy finally returns. Perhaps we owe this to similar private troubles; now the marriage to Sara is crumbling. It does inspire the poet to add some new lines, expressing the same resignation to the irreparable:

You’ve no right to be here And I’ve no right to stay Until we’re both one too many mornings And a thousand miles away.

After 1978 Dylan let the song mature for another ten years, to play it almost always (semi-) acoustically from ’88 onwards. Madison Square Garden, January ’98, is a fine example of that (definitive?) form. Sad, resigned and above all: inspired.

For the many, many colleagues who pick up “One Too Many Mornings”, the search for that final form is not that difficult at all. In the 60’s the up-tempo electric adepts (Beau Brummels, The Association) still dominate, but after that almost every cover gratefully adopts the melancholy and lets the words do the work; most of the time the accompaniment is sober, austere, almost unimportant. An apparent gender-specific appeal is striking, by the way; this is one of the rare Dylan songs in which the ladies remain on the side-lines. The few female singers who have a go anyway, miss out (well alright, Sophie Hunger’s cover is okay, 2012).

So: the men, this exceptional time. The Texan Dylan specialist Jimmy LaFave is distinctive, as is often the case, with his unique phrasing (and also limits himself to guitar and harmonica), the Englishman David Gray calls his live album A Thousand Miles Behind (2007) and delivers respectful versions of “To Ramona” and “Buckets Of Rain”, and a sensitive, lonely Mornings, and Dylan’s contemporary Jerry Jeff Walker provides an almost sentimental country version of the song (1977).

Another contemporary is Ronnie Hawkins, whose accompaniment band The Hawks will later move to Dylan (and be renamed The Band). His nameless LP from 1970 opens with a rather flat “One More Night”, but he retaliates a little later with an extremely nice “One Too Many Mornings”. Slithering dangerously close to the edge of the abyss of the Valley Of Tears, mainly due to violins and kitschy harmonica. Having a voice like Ronnie has, it is permitted, though – full and heavy, and breaking at the right moments. Granted, almost unbearably sentimental. But he’s right from his side.

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

12 years of Untold Dylan

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

Wonderful piece … would love to hear all the attempts at this song down years… Mind you, there’s a collection (43 years of Maggie’s Farm available for download) and I’d love someone to make available a similar set for One Too Many Mornings… Anyway, thanks Jochen…. keep them coming.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/475/One-Too-Many-Mornings

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan Music Box.

Hey Tony, love your analysis of his work. You have opened my ears to some of his great hidden gems. One Too Mornings is certainly one of his best songs.

I agree with you about these two wonderful covers, but I would add Totta Naslund version to the list. The delicate performance is probably my favourite.

Thanks for your kind comments Chris. Just to explain about Totta Naslund, I wasn’t able to find a youtube recording which was available worldwide, and I tend to restrict myself to covers where I can put up a freely available online version.