by Jochen Markhorst

It’s the only album title he puts between inverted commas, “Love and Theft”, which seems to send a message. Double quotes – why does Dylan use them here? We know by now that he has stuffed this album with “lovingly stolen” melodies, text fragments and licks. Lyrics are partly copied, song titles borrowed, melodies ripped, arrangements replicated. For every song on the album there is a source on at least one of these four fronts, most of them have more than one. Even the album title already exists; in 1993 Eric Lott published Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, the subject of which is close to Dylan’s heart and it’s quite likely he knows the book. It tells, as the subtitle reveals, the history of white artists with blacked faces singing black musicians’ songs – the line to the white Dylan, who draws quite a lot from the repertoire of black artists such as Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell and Robert Johnson on this record, is easily laid.

It’s the only album title he puts between inverted commas, “Love and Theft”, which seems to send a message. Double quotes – why does Dylan use them here? We know by now that he has stuffed this album with “lovingly stolen” melodies, text fragments and licks. Lyrics are partly copied, song titles borrowed, melodies ripped, arrangements replicated. For every song on the album there is a source on at least one of these four fronts, most of them have more than one. Even the album title already exists; in 1993 Eric Lott published Love & Theft: Blackface Minstrelsy and the American Working Class, the subject of which is close to Dylan’s heart and it’s quite likely he knows the book. It tells, as the subtitle reveals, the history of white artists with blacked faces singing black musicians’ songs – the line to the white Dylan, who draws quite a lot from the repertoire of black artists such as Charley Patton, Blind Willie McTell and Robert Johnson on this record, is easily laid.

But is the album title therefore also a direct reference to the book title? In his autobiography Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan mentions dozens of book titles – never putting them in quotes, but always italicising them. Inverted commas he reserves for song titles and direct speech. The album title does not fall into either of these categories. So? Does Dylan place the album title in quotation marks to indicate irony?

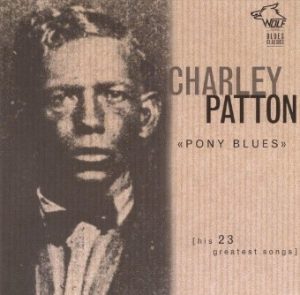

Maybe he is already covering himself, not unwittily, after the plagiarism accusations following Time Out Of Mind. Not inconceivable. “Okay. This time I’ve written in big bold letters that it’s all been lovingly stolen, right?” Or he honours, somewhat cryptic, Charley Patton also indirectly (more directly with the song “High Water”). Two years before this reference, the fine sampler «Pony Blues» has been published, that is undoubtedly also in Dylan’s cabinet. Which has all those superfluous quotation marks on both sides of the title, too. The lovingly stolen classics “High Water Everywhere” and “Down The Dirt Road Blues” are on this sampler, as well as “Pony Blues” of course, whose blues scheme and ambiguous metaphors can be found on Street-Legal, in “New Pony”.

Maybe he is already covering himself, not unwittily, after the plagiarism accusations following Time Out Of Mind. Not inconceivable. “Okay. This time I’ve written in big bold letters that it’s all been lovingly stolen, right?” Or he honours, somewhat cryptic, Charley Patton also indirectly (more directly with the song “High Water”). Two years before this reference, the fine sampler «Pony Blues» has been published, that is undoubtedly also in Dylan’s cabinet. Which has all those superfluous quotation marks on both sides of the title, too. The lovingly stolen classics “High Water Everywhere” and “Down The Dirt Road Blues” are on this sampler, as well as “Pony Blues” of course, whose blues scheme and ambiguous metaphors can be found on Street-Legal, in “New Pony”.

The beautiful finale to Dylan’s record, “Sugar Baby”, is a love theft, too. Musically it hardly differs from Gene Austin’s 1927 “The Lonesome Road”. Dylan adds a very nice descending melody line to the chorus, and that is about the only difference. Tempo, arrangement and melody are all replicated one-on-one and despite a different instrumentation the sound is also the same. Dylan has put a lot of love and energy into the search for precisely this sound, which he was able to find in the end thanks in part to a newly gained confidence in digital recording technology (the studio log mentions no less than 28 DAT IDs and eleven multitrack recordings).

https://youtu.be/uYz9q3VwRrQ

“The Lonesome Road” is deep in Dylan’s DNA. The song is on the repertoire of dozens of artists until well into the 1950s and there are more than 200 recordings of the song. The bard probably gets to know the monument through the Sinatra version – Ol’ Blue Eyes opens his popular TV show with the song in 1957. That version, like the recording, is cool, jazzy and almost cheerful.

But Dylan is apparently really touched by Austin’s original. Austin inspires him more than once, by the way: Gene Austin’s records also include titles such as “Ramona”, “Tonight You Belong To Me” and “Someday Sweetheart”. Dylan, however, borrows this particular title from another great name at the beginning of the 20th century: the first recording of Dock Boggs with his banjo (1898-1971) is called “Sugar Baby”. Incidentally, that same day in 1927 Boggs records “Danville Girl”, to which Dylan will refer with the title “New Danville Girl” (eventually changing it into “Brownsville Girl”, 1985).

From the lyrics the master mainly borrows the line that will become his closing line. “Look up, look up and greet your maker / For Gabriel blows his horn,” Austin wrote, and that apocalyptic line remains virtually unchanged, with which Dylan ends his album ominously. The other lines of text are partly copy/paste – the opening lines for example were originally intended for “Can’t Wait”, as we know from the alternative version on Tell Tale Signs (2008) – and partly inspired by other sources.

The second verse exudes Mark Twain influence. “I’m staying with Aunt Sally, but you know, she’s not really my aunt” recalls Huckleberry Finn finding shelter with the motherly Aunt Sally, whom he has told that he is her nephew. But you know, she’s not really his aunt. And though the ambiguous bootleggers reference is written shortly after the release of part 4 of the successful The Bootleg Series (and shortly before Vol. 5: Bob Dylan Live 1975, The Rolling Thunder Revue is to be released), the expression, given the bard’s documented aversion against illegal recordings, probably refers to alcohol smugglers. Although the recently surfaced anecdote about music bootleggers, recorded by Tony Glover, is amusing.

The date is 4 October 1971 and Dylan and his then wife Sara just attended a David Crosby and Graham Nash concert, which bored him quite a bit.

After the concert, Bob and Sara wandered out of Carnegie Hall and suffered the indignity of street-side vendors selling bootleg versions of his unreleased songs and live concerts. “Last night we were walking down Seventh Avenue, and on the corner was this cat hawking bootleg records, just “Bootleg records, bootleg records, get ’em here.” Just hawking ’em right on the street,” Dylan fumed. “I saw one. There was one he had of mine called Zimmerman. And I caught it just out of the corner of my eye going by, and uhhh … I was with my wife, and we went back and said, ‘Gimme that record.’ She grabbed the record from him and said, ‘Punk!’ — and we just took it, man, and split, just walked away with it.”

Funny, but underneath, Dylan’s opinion of bootlegs shines through clearly enough; he finds it a terrible phenomenon. No, with this one reference in “Sugar Baby” (“Some of these bootleggers, they make pretty good stuff’) at least the poet himself will think mainly of the illegal distillers and rumrunners. Fits better with the archaic tone of the song at all and of this verse in particular – the obvious association with “bootlegger” in a stanza that already contains a Huckleberry Finn wink is the nearby other Great American Novel, The Great Gatsby;

“Who is this Gatsby anyhow?” demanded Tom suddenly. “Some big bootlegger?” “Where'd you hear that?” I inquired. “I didn't hear it. I imagined it. A lot of these newly rich people are just big bootleggers, you know.”

Not too far-fetched. Much of the nouveau riche in 1927, the year in which Gene Austin recorded “The Lonesome Road” and the decade in which The Great Gatsby is set, has indeed become rich thanks to the illegal liquor trade.

The Darktown Strut, from the third verse, Dylan knows from an old Hoagy Carmichael hit (“The Darktown Strutters’ Ball”, 1950) and seems to be a reflection on bittersweet experiences with coloured women (Darktown refers to the black neighbourhoods in the big cities), after which stanza three and stanza four push “Sugar Baby” further down the lonesome road. The memento mori of the last lines, in conclusion, puts the song down as a lament once and for all.

Out of all of this, the template, the references, his own leftovers and some fresh ingredients, Dylan brews a magnificent rework of Austin’s song. Despite its timeless power, the original had already been forgotten, but thanks to the resuscitation by the thief of thoughts, the song is revived. So that it, perhaps, in about a hundred years’ time, may be rediscovered and again be resuscitated by a Dylan of the 22nd century.

——

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

12 years of Untold Dylan

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page including the adverts. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

Jochen, thanks for another perceptive and informed insight into a major Dylan song. All I’m going to suggest is that ‘Sugar Baby’ seems to me to be a good example of a song — I think there are more than a few — where the verse and the chorus or refrain address each other. That is, I hear the chorus, “Sugar Baby, get on down the road . . . ” not as a continuation or fulfillment of the verse’s sentiment or rhetorical strategy; but as a rejoinder or at least a response to the verse. Another ‘character’ sings the chorus in response — variously contradiction, affirmation more or less skewed, tangential comment — to the main thrust of the verses. Part of Bob’s multifarious play of identities in his art.

You’re a big girl [sugar baby. Might as well keep going] now.

We are actively promoting a link to this interesting topic on The Bob Dylan Project at:

https://thebobdylanproject.com/Song/id/603/Sugar-Baby

If you are interested, we are a portal to all the great information related to this topic.

Join us inside Bob Dylan’s Music Box.