by Jochen Markhorst

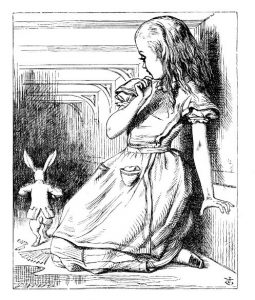

Alice has barely descended into the rabbit-hole and has just had her first disruptive experiences, and she already sighs: “I am so very tired of being all alone here!”

Alice has barely descended into the rabbit-hole and has just had her first disruptive experiences, and she already sighs: “I am so very tired of being all alone here!”

That is not the only emotion she shares with poor Mr Jones. Like Alice, and like Kafka’s Josef K. for example, Mr Jones walks around in a world whose mores are completely incomprehensible to him. The actions of the opponents do not make any sense to; the answers to his astonished questions only add to the bewilderment;

And you say, “For what reason?” And he says, “How?” And you say, “What does this mean?”

The dialogue builds a setting tending towards absurdism, a setting which is often used by writers and filmmakers. Sometimes to produce a comic effect (Jacques Tati, for example), but more often to depict oppression; the viewer or reader identifies with the protagonist and sympathizes with the alienation. Apart from Alice In Wonderland and three quarters of Kafka’s oeuvre, we also know it from films such as Antonioni’s Red Desert (1964) and Chaplin’s Modern Times (1936) and, well, even Karl Marx analyses the phenomenon of alienation as an artist’s trap in Das Kapital (1867).

This won’t be the last time Dylan makes use of it either; in half of the songs he writes for John Wesley Harding, two years later, a protagonist is lost in another reality with irrational opponents (“Drifter’s Escape”, especially, but also in “The Ballad Of Frankie Lee And Judas Priest”, “All Along The Watchtower” and “As I Went Out One Morning”). Before that, in the Basement, alienation as a motif of a song does pop up a couple of times, too. “Lo And Behold” has similar disruptive dialogues as Mr. Jones;

“What’s the matter, Molly, dear What’s the matter with your mound?” “What’s it to ya, Moby Dick? This is chicken town!”

… as “Please Mrs. Henry” gives similar, disruptive props a quasi-significant symbolism (“I’v been sniffin’ too many eggs”), and as “Quinn The Eskimo” describes similar, disruptive action scenes (“feeding pigeons on a limb”). And of course: “Million Dollar Bash”, the irresistible party song in which Thin Man Mr. Jones has a supporting role:

Then along came Jones Emptied the trash Ev’rybody went down To that million dollar bash

The suspicion that this is the same Mr Jones seems obvious given the source. It is true that “Jones” is not only a very common name in everyday life, but also a popular name in songs. “Casey Jones”, Cab Calloways “Hi-De-Ho” (“Brother Jones lived in sin / He couldn’t stop drinking gin”), the protagonist of Woody Guthrie’s “I Ride An Old Paint” is called Bill Jones, not to mention “Have You Met Miss Jones?”, and so on… the list is endless. But in “Million Dollar Bash” Dylan literally refers to the old novelty-hit of The Coasters, the Leiber & Stoller written “Along Came Jones”. And only in that particular Coasters hit is a physical aspect of the main character described:

And then along came Jones Tall thin Jones Slow-walkin' Jones Slow-talkin' Jones Along came long, lean, lanky Jones

…of all those Joneses, this is the only one who is also thin… “Along Came Jones” is indeed a Ballad Of A Thin Man.

Anyway, alienation. “Ballad Of A Thin Man” is Dylan’s first exploration of this constellation, but right away in a variant that is quite unique; unlike Lewis Carroll and Franz Kafka, and unlike Dylan’s later “alienation songs”, the omniscient narrator here is part of the opposition:

Because something is happening here But you don’t know what it is Do you, Mister Jones?

The all-knowing storyteller apparently not only knows that “something is happening”, he also suggests that he knows what “is happening”, and worse still, he mocks the helpless Mr Jones for his non-understanding.

It is a remarkable storyteller’s point of view. Kafka’s narrator always remains at a neutral, reporting distance. The raconteur of Alice In Wonderland is on the side of his protagonist, and shares – with the reader – the amazement at the irrational actions, nonsensical dialogues and absurd plot twists. And otherwise at least the audience is aware of what “is happening”; characters like Mr. Bean or monsieur Hulot also walk around like a baffled Mr. Jones, but the audience still does understand what is happening.

This narrator’s position makes “Ballad Of A Thin Man” quite unique. At Kafka, or in stories in which an earthly visitor tries to understand the mores of an extra-terrestrial civilization (Avatar, Planet Of The Apes, The Hitchhiker’s Guide), the storyteller is not the opponent of the reader or viewer. With Dylan he is. The listener has no idea what is happening either, finds it as strange and disruptive as Mr. Jones, but is not initiated by the omniscient narrator.

Both the choice of perspective and the narrator’s meanness tempt to draw a biographical line. At a young age, Dylan often barks at poets such as T.S. Eliot, and in 1978 he expresses this – mainly acted – aversion a little more specifically, explaining his already incomprehensible film Renaldo & Clara:

“Unlike trying to understand Ezra Pound or T.S. Eliot we don’t assume that we know something that you don’t know. We’re not trying to be aloof in the way that I think Pound is.”

… which describes fairly accurately what the narrator of “Ballad Of A Thin Man” does; assuming he knows something that you don’t know – and “aloof” is also a striking characterisation of this narrator. The context, reviling Eliot and Pound, suggests that the identity of Mr. Jones may also be sought in literary circles. The opening lines support this suggestion:

You walk into the room With your pencil in your hand

… the first attribute characterising the man is “a pencil”. The rest of the lyrics confirm that Mr Jones is a civilized, cultured man;

You’ve been with the professors And they’ve all liked your looks With great lawyers you have Discussed lepers and crooks You’ve been through all of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s books You’re very well read It’s well known

Furthermore, he is not impecunious (he is expected to donate generously to charity organisations), he is on friendly terms with “lumberjacks” and apparently he has imagination, hardly a reprehensible quality either – although he is attacked exactly thereon – all being hints that Mr. Jones is an arrived, successful poet. Still leaving open what those “lumberjacks” symbolise, though. Admiring reviewers perhaps, or maybe lectors.

In any case, the narrator’s intention, to ridicule Mr Jones, fails. The sympathy of the listener tends towards him, towards the poor dude who really tries to be polite and make heads or tails out of the absurdities he is confronted with. His opponents on the other hand, the geek, the midget, the sword swallower and the narrator, are all rude (“how does it feel to be such a freak?”), insulting (“you’re a cow”) and far from helpful. Petty vindictiveness seems to be an obvious explanation; the antagonists are treated “outside”, in Mr Jones’ world, as they now treat Mr Jones, as some sort of retaliation. Disrespectful, vicious and as if he were the freak.

Dylan’s own explanation of the song, as an announcement at concerts in 1978, does point in that direction as well:

“You know of the carnivals they used to have in the 50’s? You know, the ones that had geeks in them? You know what a geek is? You know what a geek is? A geek’s a man who eats a live chicken. He bites the head off, eats that. Then he eats the rest of it, heart, drinks up all the blood, sweeps up all the feathers with a broom. Anyway, in this particular carnival nobody much did want to get too tight with the geek. Even the low down people did not want to get too near the geek. One day I was having breakfast with the bearded lady, she was telling me this geek was really funky. He thinks everyone else is a little strange, he’s the only one that’s sane. And he thinks everybody else is freaky. I said “uh-hu”. Anyway, years later I was in Nashville, I think it was 1964, walking down the street with Al Kooper. Playing organ for me at the time. And we were walking down the street. We had long hair. In these days nobody in Nashville had long hair. Not Willie Nelson, not Waylon Jennings. Nobody. Anyway, we were walking down the street, buses would stop. Just because we had long hair. Anyway, somewheres along the line I put it all into this particular song.”

…rather prosaic, all in all.

Still, that doesn’t bother fans and Dylanologists, to have their own go at the lyrics – there are many who think to know what is happening.

Richard Hawley – Ballad Of A Thin Man:

This is another piece that has not available in all countries. Hopefully one of these two sources will work for you.

https://youtu.be/5ST88Ia1Utc

To be continued. Next up: Ballad Of Thin Man part II: Freaks and geeks and simples

———–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

12 years of Untold Dylan

Although no one gets paid for writing, publishing or editing Untold Dylan, it does cost us money to keep the site afloat, safe from hackers, n’er-do-wells etc. We never ask for donations, and we try to survive on the income from our advertisers, so if you enjoy Untold Dylan, and you’ve got an ad blocker, could I beg you to turn it off while here. I’m not asking you to click on ads for the sake of it, but at least allow us to add one more to the number of people who see the full page including the adverts. Thanks.

As for the writing, Untold Dylan is written by people who want to write for Untold Dylan. We welcome articles, contributions and ideas from all our readers. Although no one gets paid, if you are published here, your work will be read by a fairly large number of people across the world, ranging from fans to academics. If you have an idea, or a finished piece send it as a Word file to Tony@schools.co.uk with a note saying that it is for publication on Untold Dylan.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with around 8500 active members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

I take the message a little more straight: The thin man with the pencil is a writer – the establishment, who doesn’t know that the carnival is turning the world upside-down to where he is now the freak.