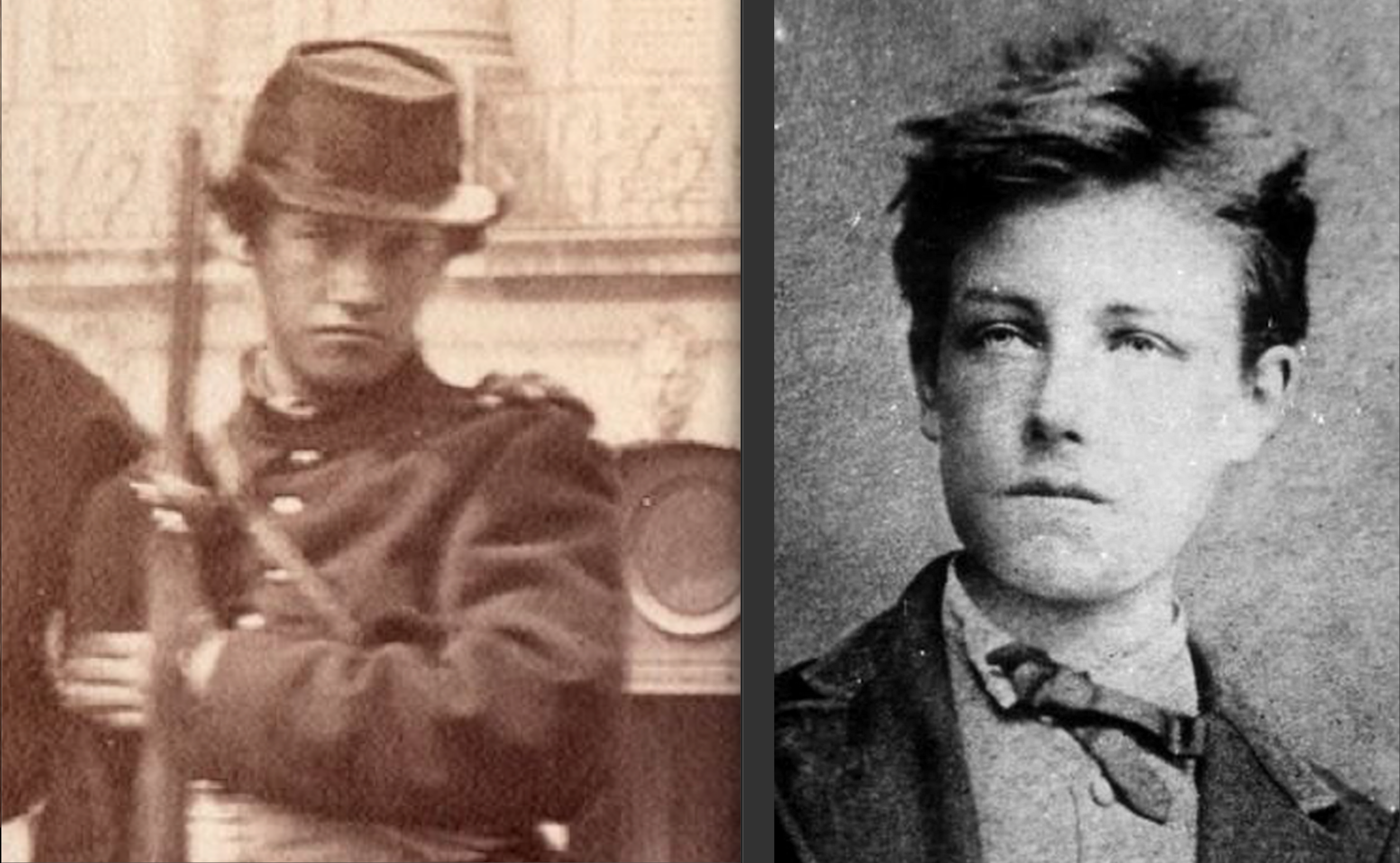

On the left the possible new face of Rimbaud, on the right the well-known Carjat studio-portrait.

Rimbaud Forever

The burnout of the messianic Arthur Rimbaud makes the mythological fall of Icarus seem more like a minor hang-gliding accident. The world’s most original modern poet autodestructs so mysteriously and so rapidly that biographers are forced to build his image out of stardust. Particles of evidence about this damned poet’s life seem to have been collected from the coma of comet Wild 2. Rimbaud is aerogel, frozen smoke, solid air. His life itself vaporizes on impact. Rimbaud defines the legend of otherness.

There isn’t much work in the Rimbaudian canon. His complete oeuvre can be read in a day and a night. (How to transform your life in twenty-four hours.) Critical texts and biographical studies pour from presses, raise eyebrows, galvanize controversy. (One can spend three lifetimes reading about the poet.) But Rimbaud’s multiform faces defy analysis. Apart from being the modern world’s poet-laureate, Rimbaud becomes in his meteoric life: teenage runaway, Abyssinian explorer, circus manager, angel of deviance, venture capitalist, philosophical freedom-fighter, Gnostic magician, Wandering Jew, pseudonymous mariner, Moslem prophet, African ethnographer, amateur photographer, gun runner, Communard and finally, military deserter. The list seems to never end. (Rimbaud forever!)

Old Plates

Three major problems exist for Rimbaud studies. First, why did he abandon poetry at eighteen when he had almost single-handedly reinvented the art? Second, what was the exact nature of his relationship with his mother, the tight-fisted but highly intelligent woman the poet venomously nicknamed Shadowmouth? And third, what happened to Arthur Rimbaud during the superviolent Paris Commune when, in the spring of 1871, the French capital was in the hands of a revolutionary government for seven weeks?

The first two questions are monolithic difficulties. And the third has also seemed insoluble – until now. Very recently, while researching Rimbaud’s circle of friends in London (all of them political exiles like him) I came across two photographs taken in the Place Vendome at the height of the demographic convulsion which was the Paris Commune. As luck would have it I enlarged one of these old plates and – suddenly – there right in front of me I seemed to see the sacred presence, the most elusive man in belles lettres, Arthur Rimbaud, the man ‘shod with the wind’.

Rimbaud as Paris Irregular during the Commune. In a follow-up article I will be discussing the identity of the giant to the poet’s right.

A Searing Gaze

In these two photographs (by Bruno Braquehais) we see the poet as we have never seen him before. Here we discover explosive and controversial evidence that Rimbaud was radically involved in the Paris Commune. From these old photographic plates we learn that the poet became nothing less than a juvenile figurehead of revolution. We see him dominating a great public space, surrounded by members of the National Guard; or possibly by the Paris Irregulars: or both. With a searing gaze the poet looks straight into the camera. Recovering from the shock of that gaze we register next that almost everyone apart from the young poet is smiling. Only Rimbaud, with his incredibly distinctive lips, downturns his mouth in an iconic scowl. Now for the first time we really see the Rimbaud grimace, echoed by a million rock-stars (from the second Carjat studio-portrait). But here in the new image that grimace is amplified and intensified.

The second point of interest is that the hard-bitten, middle-distance characters – nasty fellows to a man – all give pride of place to Arthur Rimbaud. It’s not just that the poet stands on a pedestal while they stand further off. No, here we see psychological deference. Whoever he is, this young man on the plinth is so charged with charisma and electricity that he commands the respect of men much older than him. And that could be because this wildman in his grimy kilt of serge, this Lord of the Dance with his regulation rifle, this holy monk of androgynous demeanour is actually Arthur Rimbaud, freedom-fighter. (It is my belief that Rimbaud was quite well-known as a poet during the Commune, though this fame mostly resonated at street-level.) In this new portrait we seem to meet the ‘dear, great soul’ – Verlaine’s words – while understanding that Camus was absolutely correct when he famously called Rimbaud ‘the poet of revolt’.

The full image, shot by Bruno Braquehais some time after 16 May 1871.

Rebel Angel of the Place Vendome

How can we contextualize this theophanic surfacing? What is the setting for Rimbaud’s emergence in this image?

In both of these Bruno Braquehais portraits we are in the Place Vendome in May of 1871. At the height of the Commune an exorcism of empire is being – or has recently been – enacted. As the Communards see it the Rue de la Paix (Peace Street) is being polluted by the presence of Napoleon Bonaparte on top of the column he set up to commemorate Austerlitz. And after much discussion, spearheaded by the painter Gustave Courbet, they finally decree its demolition. And precisely where the Rue de la Paix begins – in the Place Vendome – Arthur Rimbaud is presiding over the exorcism. He takes up a military stance – first at the feet and then at the head of Napoleon – who is represented as a laurel-crowned Caesar. (We know the poet was recruited to the Paris Irregulars so his uniform is not problematic.) But clearly Rimbaud is more than soldier here. The whole grouping is highly choreographed and the poet has been given an emblematic role. He is high-priest at this revolutionary mass where verticality stands for hierarchy. What delights is that the poet is so cheekily poking fun at the figure of the prostrate Bonaparte. We can only interpret his body-language to mean that he has just used his left elbow to overthrow the Nightmare of Europe.

Brute force and easy pride have fallen. A symbol of barbarism lies in the dust. Paris has been cleansed of Napoleonic earth-magic. Triumphalist and negative symbolism has been defused. (The workers of Paris are not to be treated like idiots.) The 50,000 dead of Austerlitz are no longer insulted. These are the thoughts in Rimbaud’s mind as he gazes into the future from the Place Vendome.

Two mindblowing portraits of Arthur Rimbaud have been hiding in plain sight for more than a century. If they are genuine they are possibly the most dramatic visual study of any poet in the history of the West. Byron, for all the freedom-fighting in Greece, never assumed such a Byronic pose. If Chatterton in his fatal attic had been captured by camera obscura; if Pushkin had been filmed striding through the snow to his doom; if John Donne had been photographed in the pulpit of St Paul’s in the moment of saying No man is an island; if some prehistoric daguerrotype existed which showed us Dante climbing the staircase of exile: then we would have images to place beside Rimbaud in the Place Vendome.

The second Braquehais image. Here Rimbaud (fifth from the right) adopts exactly the same posture as in the first image.

The series continues…

Meanwhile elsewhere

There are details of some of our more recent articles listed on our home page. You’ll also find, at the top of the page, and index to some of our series established over the years.

If you have an article or an idea for an article which could be published on Untold Dylan, please do write to Tony@schools.co.uk with the details – or indeed the article itself.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with getting on for 10,000 members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

You’d think Rimbaud might mention that he participated in such an important event in one of his poems, but there is no poetic or documented evidence that he was in Paris at the time. It’s claimed that he wrote poems up until he was 20.

The photo looks quite a bit like him, but unfortunately it is not labelled.

The dust bin of history, one can say, is indeed ‘dusty’.

The mouth, chin, and hair look right, but the nose is wider and flatter in the found photo than in the Carjat photo. It would take a lot of scholarly research to put him in that precise place at that moment. Thank you for sharing, and keep and eye out for a lost Rimbaud manuscript from the final twenty five years of his life.

Nice article but case unproven. A reputable historian summarizes as follows :

“1871 Leaves Charleville on 25th February, sells his watch in order to buy a ticket for Paris. Remains at Paris until 10th March. 15th of May (six days before la semaine sanglante) Rimbaud sends a letter from Charleville to Paul Demeny which includes his Chant de Guerre Parisien. September finds him at the home of the Verlaines in Paris.” Therefore, casting aside phony photographs of someone in a uniform Rimbaud would never wear, we have still to account for his whereabouts. James Graham