by Jochen Markhorst

More Than Flesh And Blood (1978) part I: Lousy poetry

II Johnnie, that’s called songwriting

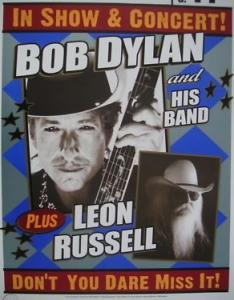

In 2004, English music journalist and author Peter Doggett writes the wonderful article “Whose Masterpiece Is It Anyway?” for the fanzine Judas! about Dylan’s recording sessions with Leon Russel in March 1971. Those are the sessions that yielded “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece”, and when Doggett interviews Leon Russel about it over thirty years later, the pianist still has vivid and colourful memories.

In 2004, English music journalist and author Peter Doggett writes the wonderful article “Whose Masterpiece Is It Anyway?” for the fanzine Judas! about Dylan’s recording sessions with Leon Russel in March 1971. Those are the sessions that yielded “Watching The River Flow” and “When I Paint My Masterpiece”, and when Doggett interviews Leon Russel about it over thirty years later, the pianist still has vivid and colourful memories.

Russel apparently has Dylan’s sympathy and admiration. Not only does Dylan accept Leon’s invitation to record something together, he also agrees to a special request from the long-haired music beast. Russel has heard the stories of a Dylan who writes his songs between the studio racket, ping-ponging musicians and the coffee ladies, the Dylan who, while the producer and musicians are listening back to the recording, is already working on the next song.

“I’d like to see you do that!” I begged him and begged him, and after a little while he agreed to show me. So I called my guys – Carl Radle on bass, Jimmy Keltner on drums, and [Jesse] Ed Davis on guitar – and we went up to Blue Rock Studios in the Village, and I cut these two tracks for Bob. It took about 30 minutes. Then Bob came down, and I said, “let me see you write songs to these”.

And Dylan, Russel tells, does allow Leon to hang around him all afternoon and look over his shoulder as he writes:

“He let me watch him as he wrote the songs Watching the River Flow and When I Paint My Masterpiece. That song actually refers to that event: There’s a line in there that goes, `You’ll be right there with me when I paint my masterpiece’ – he was referring to me watching him write!”

It is a charming and informative report, but one insight remains underexposed: Russel had already recorded the music, or at least the basic tracks. When Dylan arrives the track is played, on repeat, while Dylan writes the words to it. “And then when he’d got the words the way he liked, he cut the vocals.”

Both songs are in the name of Dylan alone; neither Russell nor anyone else has credit for either song. Evidently, the accompanying music is considered trivial confectionery; the lyrics are the song. Russel doesn’t make a point of it – he neutrally calls it “a chord sequence” that he got from somewhere, and for “Watching The River Flow” he copies a riff he’s used before (for “Dixie Lullaby”, from his 1969 debut album). No big deal, apparently.

It is a mentality in which Russel is not alone. Music history has dozens of examples of relatively unknown sidemen who didn’t think or realise that they had actually made the music for which the bandleader got the credit. A most remarkable example is told by Keith Richards in his autobiography Life (2010) and concerns Chuck Berry, or rather his pianist Johnnie Johnson:

“I asked Johnnie Johnson, how did “Sweet Little Sixteen” and “Little Queenie” get written? And he said, well, Chuck would have all these words, and we’d sort of play a blues format and I would lay out the sequence. I said, Johnnie, that’s called songwriting. And you should have had at least fifty percent. I mean, you could have cut a deal and taken forty, but you wrote those songs with him. He said, I never thought about it that way; I just sort of did what I knew.”

… Johnnie Johnson even uses comparable wording as Russel to downplay the importance of his contribution (“sequence”, “blues format”).

In that interview with Peter Doggett, Russel reveals even more intriguing details about the origins of the accompanying music:

“When he first started writing it, he wrote, I left Rome and landed in Brussels/With a picture of a tall oak tree by my side – I think that he thought the changes that I’d played were “A Tall Oak Tree”, though they were actually “Rock Of Ages”, which I think “A Tall Oak Tree” was taken from as well. Anyway, he changed those lines later.”

Shortly afterwards, Dylan visits his old comrades in arms of The Band who are busy recording their fourth LP, Cahoots. The record is almost entirely written by Robbie Robertson, but a Dylan song can never hurt, of course. Dylan donates “When I Paint My Masterpiece”, with minor lyric changes; the line “with a picture of a tall oak tree by my side,” is changed to “on a plane ride so bumpy that I almost cried.”

Russell’s analysis of the deleted words is the second glimpse he gives into Dylan’s songwriting process. Choosing “painting a masterpiece” as a metaphor for “writing a song” is quite clear, obviously, but how Dylan incorporates Russell’s observing presence in the line she’d be right there with me when I paint my masterpiece is a beautiful, uncloaking insider’s tip. Just like this second piece of information, that the words tall oak tree enter the song because Dylan thinks he hears “Tall Oak Tree” in the chord sequence.

“Tall Oak Tree” is a song that keeps buzzing around in Dylan’s head throughout the 1970s. We know this thanks to the entertaining Billy Brunette, who in the 2015 podcast StageLeft cheerfully talks about his adventures as guitarist in Dylan’s band (in 2003 he replaced Charlie Sexton for the eleven concerts in Australia and New Zealand) and shares his private memories of Dylan:

“We talked a lot about my dad and my uncle. He was a fan of some of their music. He was a big Rick Nelson fan. So, he really liked that stuff and… I had actually met him in the seventies, and he told me that my Dad’s song, “Tall Oak Tree”, he said he realised that was the first ecology song ever written. And I called my dad the next morning, and I said ‘Hey Dad, I ran into Bob Dylan’. That’s neat, you know.”

Presumably this is a memory from around 1977. At that time Billy frequents the Sundance Saloon in Calabasas, where colleagues like Leon Russel, Emmylou Harris and Jackson Browne regularly enjoy a quiet beer – and so does Bob Dylan, who lives nearby (Calabasas is a town in the Santa Monica Mountains, about twenty miles from his home in Malibu). Billy’s uncle is Johnny Burnette, together with Billy’s father Dorsey one of the founding fathers of rockabilly. In fact, rockabilly is called rockabilly because Dorsey and Johnny in 1953 wrote the hit “Rock Billy Boogie” about their new-born sons Rocky and Billy.

Billy’s father Dorsey scores a hit with “Tall Oak Tree” in 1960, and there are hints that Dylan played the single more than once; the B-side features “Juarez Town”, whose setting returns in “Just Like Tom Thumb’s Blues” and whose La Bamba drive echoes in “Like A Rolling Stone”. The A-side then Dylan thinks hearing in Leon Russell’s template for “When I Paint My Masterpiece”. He recycles the words tall oak tree for his lyrics, and in 1978, when he is tinkering with songs with Helena Springs, another lyric fragment reverberates:

The Creator looked down And saw everything was love, love, love. Then he took a bone And a piece of mud -- He made a man and a woman To be flesh and blood.

Though, in the context of this particular song, sung by this particular power lady, tracing “flesh and blood” back to Aretha would be more obvious:

A woman's only human You should understand She's not just a plaything She's flesh and blood just like her man If you want a do-right-all-day woman (woman) You've got to be a do-right-all-night man (man)

To be continued. Next up: More Than Flesh And Blood part III: Do right man

————————-

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits (only German)

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

What else?

There are details of some of our more recent articles listed on our home page. You’ll also find, at the top of the page, and index to some of our series established over the years.

If you have an article or an idea for an article which could be published on Untold Dylan, please do write to Tony@schools.co.uk with the details – or indeed the article itself.

We also have a very lively discussion group “Untold Dylan” on Facebook with getting on for 10,000 members. Just type the phrase “Untold Dylan” in, on your Facebook page or follow this link And because we don’t do political debates on our Facebook group there is a separate group for debating Bob Dylan’s politics – Icicles Hanging Down

I very rarely disagree with anything you write Jochen, but I think there is a little more to the issue of writing chord sequences to be explored. It’s extraordinarily rare to find a song with a new sequence in it, which means all songwriters are copying what’s been done 1000 times before.

More than that, the bands I played in (which of course didn’t include anyone who has made it to the hit parade) always started a rehearsal spending time improvising around a chord sequence someone started playing. It was a sort of way of warming up. When I went for an audition as keyboard player with Soft Machine, they tested me out by playing in C sharp, just to see if I could. (I didn’t get the gig).

And as such the chord sequence is the easy bit. It’s the doing something with it that makes the song. So I am not too sure anyone would ever be able to make a copyright claim out of a chord sequence.

*Leon Russell