Gates Of Eden (1978) part I: The Lady In The Water

by Jochen Markhorst

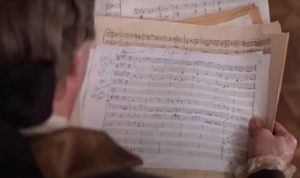

Salieri is not dismissive. Constanze may leave the manuscripts here, he will study them and then judge whether the work of her husband, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, is good enough for a job as court composer. But alas, that is not really an option. Contanze cannot possibly leave the manuscripts here. She has taken them away secretly; she has approached Salieri behind Mozart’s back. Should Wolfgang discover they are missing, all hell would break loose. “You see, they’re all originals.” Confused, Salieri opens the folder and leafs through the sheet music. Are these originals? “Yes, sir. He doesn’t make copies.” Salieri gasps. The flashback is broken off; we are back in the present, in the Vienna of 1823, where an elderly, embittered Salieri is telling his story to a shaken, non-understanding young priest, to Father Vogler.

Salieri is not dismissive. Constanze may leave the manuscripts here, he will study them and then judge whether the work of her husband, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, is good enough for a job as court composer. But alas, that is not really an option. Contanze cannot possibly leave the manuscripts here. She has taken them away secretly; she has approached Salieri behind Mozart’s back. Should Wolfgang discover they are missing, all hell would break loose. “You see, they’re all originals.” Confused, Salieri opens the folder and leafs through the sheet music. Are these originals? “Yes, sir. He doesn’t make copies.” Salieri gasps. The flashback is broken off; we are back in the present, in the Vienna of 1823, where an elderly, embittered Salieri is telling his story to a shaken, non-understanding young priest, to Father Vogler.

OLD SALIERI

Astounding! It was actually beyond belief. These were first and only drafts of music yet they showed no corrections of any kind. Not one. Do you realize what that meant?

Vogler stares at him.

OLD SALIERI

He’d simply put down music already finished in his head. Page after page of it, as if he was just taking dictation. And music finished as no music is ever finished.

(Amadeus, 1984)

It is not even too romanticised, this scene. Although Mozart’s widow committed the atrocity of throwing away sketches and cutting up manuscripts in order to earn money by selling strips of “original Mozart”, enough manuscripts have been preserved to confirm the essence of Salieri’s bewilderment: Mozart wrote down his masterpieces almost without errors, corrections or erasures. The difference with, for instance, the battlefields that Beethoven or Mahler put down on paper, is huge. And it is also in line with Mozart’s own statements about his working methods, such as in this letter to his father from 1780:

“Nun muß ich schliessen, denn ich muß hals über kopf schreiben – komponirt ist schon alles – aber geschrieben noch nicht (Now I have to close, because I have to write head over heels – everything is already composed – but not yet written).”

In the miraculous Horn of Plenty The Bob Dylan Scrapbook 1956-1966 (2005), there is a reproduction of Dylan’s original draft for “Gates Of Eden” folded between pages 40 and 41, which evokes a sensation similar to Salieri’s. It seems to have been written down in one go, has hardly any corrections and is almost finished. As if he was just taking dictation. Only the last verse lacks the middle part; with no attempts to shovel the glimpse / Into the ditch of what each one means is the sole thing that was thought up later.

Remarkable, but not very surprising; we know the testimonies of studio technicians, producers, session musicians and colleagues, who tell how Dylan, between takes, comes up with complete, perfect song texts. No, the true richness of such a manuscript lies on another level: it provides some insight into the creative process, into the workings of Dylan’s poetic vein.

Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds

Apparently, the poet initially had something different mind. In terms of form, at least, it is striking: four-line stanzas, i.e. quatrains, and from the third stanza onwards, he decides on an AAAB rhyme scheme. Here, also graphically, on paper, all opening lines are fourteeners – the dividing forward slashes are clearly inserted later. There are a few deviations in terms of content, Dylan makes punctuation errors (it’s instead of its, for example) and the few deletions are all readable. In content, the first verse is slightly different from the final version:

Of war and peace / the truth does twist / it’s curfew gull just glides / Upon the fungus forest cloud, the cowboy angel rides An tho he lights his candle in the sun, it’s glow is waxed in black All ecpt when neath the trees of Eden ______

Twice the error it’s (instead of its), the third line first read An tho his candle burns the day, is crossed out during this drafting phase and changed to he lights his candle in the sun and after the writing and correcting of this manuscript is finally rewritten to with his candle lit into the sun, and the most striking, the most interesting: on the place of the incomprehensible four-legged forest clouds was initially the relatively normal, reducible fungus forest cloud.

It’s quite a giveaway. Any doubts regarding Dylan’s initial angle to this lyric evaporate now. The atomic bomb, obviously. How we definitively forfeited our right to reaccess Eden by dropping the bomb, something like that. The insight into the creative process is almost voyeuristic. The poet evidently wants to avoid mushroom cloud. Although “mushroom cloud” is a powerful, highly visual metaphor, it has long since been chewed out and has become so commonplace that its poetic brilliance has faded away. So, the poet chooses the closest association: fungus.

At this point in the creative process, the poet still seems to want to work towards the trees of Eden, and to write in fourteeners, and the mushroom cloud resembles a tree as much as a member of the kingdom Fungi, and an alliteration is always welcome, so: fungus forest cloud it shall be. Dylan probably writes this shortly after the last song he writes for Another Side Of, after “My Back Pages”, so around mid-June 1964. The first live performance is the one on 31 October in New York, the concert that hits shops as The Bootleg Series Vol. 6: Bob Dylan Live 1964, Concert at Philharmonic Hall in 2004.

Thus, sometime between mid-June and late October, Dylan changed that fungus to four-legged, and the obvious explanation is a desire for mystification or, to put it more kindly, a penchant for poeticisation. In those months, the young poet has walked past Lombardi’s on Spring Street and John’s Of Bleecker Street dozens of times, seen pizza al funghi on the menu dozens of times – and at some point he probably thinks: fungus, no, too obvious, too forced, too in-your-face. But he does want to keep the forest, and the alliteration too. The bomber already is a “forbidden bird, a curfew gull”, the pilot is a cowboy angel, a winged weapon carrier… an associative mind just might arrive via world destruction, cowboy angel, the Apocalypse and the Four Horsemen at four-legged.

The all-too-obvious atomic bomb reference of the original verse His candle burns the day, the other no-brainer, has already been blurred by Dylan in the conception phase and will thus be blurred even further. However, the paraphrase of Oppenheimer’s famous quote from the Bhagavad Gita (“Brighter than a thousand suns”) is still recognisable. Especially because of the continuation, which concludes that this sky-burning candle has a black afterglow, that it will bring Death. Or, as Oppenheimer said in response to that first atomic test: “Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds.”

The closing line, all ecpt when neath the trees of Eden, confirms that the young poet Dylan is initially in this rather one-dimensional, almost topical corner. After all, we only know of two trees in Eden: the Tree of Life and the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil – two concepts steeped in symbolism, effortlessly fitting into an apocalyptic theme.

Well, perhaps anyway. The truth, as we all know, just twists.

To be continued. Next up: Gates Of Eden part III: Hello lamppost, nice to see ya

—————–

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

——————

Publisher’s Footnote: we are currently evolving a page which provides links to some of the most interesting cover versions of Bob Dylan songs – you can find the latest edition at

Dylan covers, 2nd edition: 50+ new covers added, now over 150 in total

The track above will most certainly be added to the next iteration.

————

Incomprehensible?

Me thinketh that the four-legged cloud looketh very much like the cowboy angel’s horsey ….what saith thou Jochen?

Mja… I’d go along with a four-legged cloud, I suppose. Though I’ve never seen one, I should add. But a “four-legged forest cloud”?

Don’t get smart with me young man- it’s turtles all the way down –

A superlative play on words…the ‘foremost’ horsey – the “fore-est” one

There was that time in the big 3 albums, Bringing It All… Blonde on Blonde and Highway 61 where there was a disconnect between what Dylan imagined and what words went down on paper. These incomprehensible or garbled phrases are just what they appear to be – drug fueled images that aren’t well constructed or that don’t stand up to a rigorous examination by the discipline of poetry. Beneath the wordplay is just a fog of blurred thought. If Dylan at the time knew what he meant, well, he was the only one. In stark contrast, the lyric precision of his later songs, from Oh Mercy on, is masterful, (in most cases) and stands up to examination.

Martini?

No I said ‘martinum” ! – if I wanted more than one, I would have asked for more than one….

“Disconnected”, you say?? – three of the greatest albums ever made!

That others beside yourself don’t ‘get’them is extremely presumptious on your part.

I disagree your assessment completely …..most of the other albums are indeed fine ones but pale somewhat when compared to the Big Trinity.

I love those big 3 albums but I still tend to agree with Bill Routhier. In 1967 Lennon wrote ‘I Am The Walrus’ as a gobbledygook riposte and went on to talk about Dylan of this time ‘getting away with murder’.

‘Gates Of Eden’ is a po-faced dirge. Just about my least favourite track on the Big Trinity.

Yes, Oh Mercy is great.

Having all those ‘promises of paradise’ trampled on is not everyone’s cup of tea that’s for sure.