by Jochen Markhorst

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part I: Rose of England

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part II : A Song Of Ice And Fire

- Love Minus Zero/No Limit (1965) part III: I love you, but you’re strange

IV The Order of the Whirling Dervishes

People carry roses Make promises by the hours My love she laughs like the flowers Valentines can’t buy her

“I used to recite prayers. Now I recite rhymes and poems and songs,” says Rumi, probably around 1260, about his “ecstatic poetry”, in one of his thousands of ghazals. Rumi’s ghazals (short poems consisting of rhyming couplets) and quatrains are basically one long ode to the liberating, uplifting qualities of song, dance and love, and he is still honoured in that vein: as a prophet of Love, Song and Dance. After Rumi’s deeply regretted death in 1273, Sultan Walad comes up with perhaps the most fitting tribute: he founds The Order of the Whirling Dervishes, the order that is still famous for its religious ritual, for its wildly spinning monks, reciting poetry and prayers, in order to get closer to God in a religious ecstasy.

“I used to recite prayers. Now I recite rhymes and poems and songs,” says Rumi, probably around 1260, about his “ecstatic poetry”, in one of his thousands of ghazals. Rumi’s ghazals (short poems consisting of rhyming couplets) and quatrains are basically one long ode to the liberating, uplifting qualities of song, dance and love, and he is still honoured in that vein: as a prophet of Love, Song and Dance. After Rumi’s deeply regretted death in 1273, Sultan Walad comes up with perhaps the most fitting tribute: he founds The Order of the Whirling Dervishes, the order that is still famous for its religious ritual, for its wildly spinning monks, reciting poetry and prayers, in order to get closer to God in a religious ecstasy.

Seven centuries later, its magic has not worn off:

Take me on a trip upon your magic swirlin’ ship My senses have been stripped, my hands can’t feel to grip My toes too numb to step Wait only for my boot heels to be wanderin’ I’m ready to go anywhere, I’m ready for to fade Into my own parade, cast your dancing spell my way I promise to go under it

… Dylan’s Mr. Tambourine Man is a twentieth-century dervish, who even properly adheres to the prescribed choreography of the Order (Far from the twisted reach of crazy sorrow / Yes, to dance beneath the diamond sky with one hand waving free); spinning round and round, with one hand raised above the head.

That, of course, is not the only line between Dylan and Rumi; “I recite rhymes and poems and songs” is a perhaps very compact but also a very apt one-liner to summarise Dylan’s life and work, and beyond that the confrères seem to think and write in similar imagery – the kind of imagery that borders on synaesthesia, as here, in “Love Minus Zero”.

In Western culture, it is a rather exotic image, “laughing like a flower”. Its synaesthetic content is in itself not an obstacle, but perhaps it is a little too woeful, or too childish – in any case, it does not really penetrate. In Eastern culture, the image is more popular. Thanks to Rumi, of course, who wrote in the thirteenth century: “Why so happy to laugh with your mouth shut? You should laugh like a flower, without a care,” with which he immediately defines what that actually is, “laughing like a flower” – with open mouth, that is. Fully, without embarrassment. And just to be sure, he repeats his definition in a poem: I laugh like a flower, not just mouth laughter (translating as not just the lips, or rather: not just smiling, is probably better), I burst forth with gaiety and mirth.

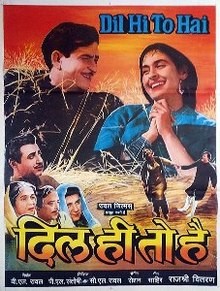

It has almost the status of a Sufi motto, and its impact can still be measured centuries later. In a 1963 Bollywood classic, for example, Dil Hi To Hai (“It Is Only A Heart”), the film that yields a whole series of now-classic Indian hits. Including “Tum Agar Mujhko Na Cha Ho To (If You Don’t Want Me)”, which became so popular partly because it was sung in the film by the greatest Indian film star of all time, Raj Kapoor. And in that song, he tries to charm his adored one, who had just been so angry with him:

Phool ki taraha hanso sab ki nigaahon mein raho Apni maasoom jawaani ki panaahon mein raho Mujhko woh din na dikhaana tumhe apni bhi kasam Mein tarasta rahoon tum gair ki baahon me raho

Laugh like a flower, be the center of everyone's attention. Stay safe in the shelter of your innocent youth. Let me not see the day, I beg you... In which I yearn for you while you’re in another man's arms.

Raj Kapoor – Tum Agar Mujhko Na Cha Ho To:

https://youtu.be/kXnHoJ5ZH44

… फूल की तरह हँसो, phool ki taraha hanso, laugh like a flower… it is not too likely, obviously, that Dylan did visit a Bollywood film in the early sixties, vehemently taking notes in the process. The shared use of this remarkable metaphor illustrates, mostly, an art fraternity across centuries, continents and cultures. On the other hand: in the twenty-first century, Rumi is still the most widely read and one of the best-selling poets in the US, and Dylan’s comrade Allen Ginsberg has undoubtedly waved Rumi’s poetry around… it is not entirely inconceivable that Dylan did, in fact, read this particular image at Rumi.

The introduction of Valentines, however, is all-American. The name does trace back to a third-century Saint Valentine, and Chaucer’s poem “Parliament Of Fowls” (c. 1380) may have contributed something as well (“For this was on seynt Volantynys day / Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make – For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day / When every bird comes there to choose his match”), but its commercialisation, from the 19th century onwards in the Anglo-Saxon world, is primarily an American success story. Oriental it is certainly not, in any case. In Islamic countries, celebrating Valentine’s Day is even forbidden – which would probably have been against the sentimental swooner Rumi’s wishes.

Anyhow, the content of Dylan’s final line in this stanza is probably primarily driven by rhyming pleasure. “Love Minus Zero” has no iron-clad rhyme scheme – the four octaves each have a different rhyme scheme. The only constants are the rhyming opening lines and the rhyming of verse four with verse eight. In this first octet Dylan shows off with the indeed nice and original rhyme find buy her – fire. Nice and original perhaps, but this particular rhyme is still not widely imitated. Dylan fan Dan McCafferty, the singer of the Scottish rock band Nazareth, borrows it in 1991 for the unimpressive opening song of the unsuccessful album No Jive, “Hire And Fire” (Setting my soul on fire / Try her and buy her). The other songs on the album are equally unmemorable. The record’s meagre highlight is the finale, a poor remake of their 1973 hit, Joni Mitchell’s “This Flight Tonight” – a brilliant cover of one of Joni’s most beautiful Valentine’s songs.

Nazareth – This Flight Tonight:

To be continued. Next up: Love Minus Zero/No Limit part V: When a sighing begins in the violins

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse