- On The Road Again (1965) part I: I don’t know why everyone is so rude

- On The Road Again (1965) part 2: The shitting Pope

On The Road Again (1965) part 3

by Jochen Markhorst

A handsome Malacca sword-cane

Your grandpa’s cane It turns into a sword Your grandma prays to pictures That are pasted on a board Everything inside my pockets Your uncle steals Then you ask why I don’t live here Honey, I can’t believe that you’re for real

It is one of the many mysterious details surrounding Edgar Allan Poe’s enigmatic death in 1849; his days-long disappearance begins when he leaves his friend Dr John Carter’s office in Richmond, leaving his own walking stick behind but taking his friend’s with him: “a handsome Malacca sword-cane,” according to Dr Carter’s own account of this evening. Poe is found five days later, semi-conscious, dressed in unfamiliar, ill-fitting, cheap clothes and unable to tell what has happened to him. The cane-sword is still in his possession. He is admitted to Washington Medical College, where he dies four days later.

It is one of the many mysterious details surrounding Edgar Allan Poe’s enigmatic death in 1849; his days-long disappearance begins when he leaves his friend Dr John Carter’s office in Richmond, leaving his own walking stick behind but taking his friend’s with him: “a handsome Malacca sword-cane,” according to Dr Carter’s own account of this evening. Poe is found five days later, semi-conscious, dressed in unfamiliar, ill-fitting, cheap clothes and unable to tell what has happened to him. The cane-sword is still in his possession. He is admitted to Washington Medical College, where he dies four days later.

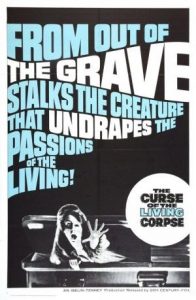

A cane-sword, or swordstick, is a nineteenth-century accessory and is mostly known to us from films and comic strips. In the days when Dylan writes his song, for example, the Paramount Theatre in New York City shows the playful horror The Curse Of The Living Corpse (Del Tenney, 1964); an old-fashioned body-count horror, in which the sinister killer perforates victims with his cane-sword, among other killing methods. An assassin from, of course, the Upper Class.

The weapon does have an appealing double whammy; it signals both civilisation and taste on the part of the carrier, as well as a life-threatening danger – and as a bonus the director gets the Vicorian, gothic connotation for free. Ideal, then, for Dr Jekyll (The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, with Jack Palance, 1968), for Sherlock Holmes (Guy Ritchie, 2009) and for Sean Connery in The Great Train Robbery (1976), to name but three examples of Victorian heroes who – usually to the relief of the audience – suddenly conjure up a sword from their walking sticks.

The grandfather in “On The Road Again” is of the same antique, aggressive ilk, but here he uses it not so much to ward off a bad guy or to commit a sneak attack, an assassination, but to further intimidate our poor protagonist. Presumably to cut off whining about the pickpocketing “your uncle”, i.e. the son of the sword-wielding grandfather.

In the midst of that aggressive, bullying, thieving, intimidating mob, of that particularly nasty in-laws, the image of Grandma seems to fall out of tune. After all, Grandma is sitting, perfectly harmlessly as it seems, praying to pictures pasted on a board. Yet something must be wrong. The narrator provides a dispiriting list of unpleasantly acting housemates and visitors. He does so rather matter-of-factly, without qualifying adjectives, but it is nonetheless a list of harassment and unpleasantness that, when added up, must explain why he doesn’t want to live here – and somewhere in the middle of that procession of pranksters, thieving uncles, aggressive grandpas and strange visitors, he points to the praying grandma. Apparently, she too is one of the factors that make it so unbearable, here in this house.

We are not given any further information, but in any case the suggestion is that grandmother is not praying to our Saviour or to sweet Saint Brigid, but to something disturbing. Baron Samedi or maybe even Baal, something like that. Or, at least as likely: the musician Dylan briefly takes over from Dylan the Narrator in this verse fragment.

This is a highly rhythmic, sound-oriented interlude, after all – it really is a line from a poetic musician. Your grandma prays to pictures that are pasted on a board is a perfect fourteener, a line of 14 syllables, made of seven iambic feet; an iambic heptameter, as the literature professor would say. The rhythm is dictated by the triple alliterating p (prays-pictures-pasted), and that the poet takes sound into account is demonstrated in the first version, where Dylan is still singing:

Your grandma prays to pictures That are posted on a board

Posted, not pasted. The sonorousness of the word, as Edgar Allan Poe calls it, is apparently the decisive factor; posted does not assonate very well with board, but pasted echoes perfectly in prays. To whom she prays is still not clear, of course. Probably to St. Paul, the patron saint of swordsmen, come to think of it. Anyway, our narrator will behold Bill Withers’ grandmotherly joy and happiness with some envy;

Grandma's hands Clapped in church on Sunday morning Grandma's hands Played a tambourine so well If I get to Heaven I'll look for Grandma's hands

To be continued. Next up: On The Road Again part 4

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

To be picky, a picture ‘pasted on’ is more securely attached than one ‘posted on’ ….so are you sure that the assonant sound is the one and only “decisive” reason for the change?(lol)