by Jochen Markhorst

- Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream Part 1: There’s very little that you can’t imagine not happening

- Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream (1965) part 2 – Blow Boys Blow

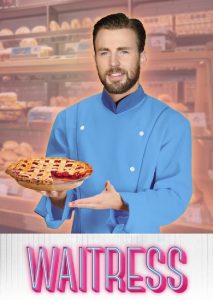

V Your waitress: Captain America

I went into a restaurant lookin' for the cook I told them I was the editor of a famous etiquette book The waitress, he was handsome, he wore a powder-blue cape I ordered some suzette, I said, "Could you please make that crepe" Just then the whole kitchen exploded from boilin' fat Food was flyin' everywhere, I left without my hat

On April 1, 2019, TheaterMania serves up the ridiculously transparent April Fool’s joke that the very tough, very macho Captain America Chris Evans has been won over to headline a gender-bending lead role in a musical: “BREAKING: Chris Evans to Become First Male Jenna in Waitress on Broadway”. Clickbait, of course, and the article is accompanied by a – not too professionally – photoshopped Evans-as-waitress. Waitress in itself is well chosen, by the way. The successful musical version of the 2007 indie film is an all-female production, with a female director (Diane Paulus), a female music writer and lyricist, a female choreographer and a female scriptwriter. To have the female lead played by an ultimate he-man would be amusing self-mockery bordering on irony.

On April 1, 2019, TheaterMania serves up the ridiculously transparent April Fool’s joke that the very tough, very macho Captain America Chris Evans has been won over to headline a gender-bending lead role in a musical: “BREAKING: Chris Evans to Become First Male Jenna in Waitress on Broadway”. Clickbait, of course, and the article is accompanied by a – not too professionally – photoshopped Evans-as-waitress. Waitress in itself is well chosen, by the way. The successful musical version of the 2007 indie film is an all-female production, with a female director (Diane Paulus), a female music writer and lyricist, a female choreographer and a female scriptwriter. To have the female lead played by an ultimate he-man would be amusing self-mockery bordering on irony.

And the colour of Chris Evans’ clothes on the photoshopped poster is just as well chosen: powder-blue.

The cape of Dylan’s male waitress is powder-blue too, which is a fitting colour anyway: powder-blue is as difficult to define as the timeline along which the protagonist moves. Throughout the centuries it has been used for different shades of blue, but since the 20th century we all agree on a dusty, pale shade of blue. In 2021, it happens to be trendy again; both fashion collections and car manufacturers (Toyota, for example), concentrate on colours like pink, lilac and blush – and powder-blue, too. Still, the colour indication is as rare in the twenty-first century as it was in 1965.

In Dylan’s bookcase it can probably only be found once or twice. Once in the work that is on Dylan’s bedside table in these months, judging by the many references in the songs he writes in these mercurial 500 days: William S. Burroughs’s The Soft Machine from 1961. In one of the many homoerotic scenes:

“He was lying on a lumpy studio bed in a strange Room – familiar too – in shoes and overcoat – someone else’s overcoat – such a coat he would never have owned himself – a tweedy loose-fitting powder-blue coat.”

That, LBGTQ or effeminacy, seems to be the connotation anyway. In Funny Girl, the mega-hit that already has been running at The Majestic for several months as Dylan records “115th Dream” half a mile away, the colour comes along once (A rootin’, shootin’, ever-tootin’ Dapper Dan who carries in his satchel a powder-blue Norfolk suit, “Cornet Man”) and Dylan uses the bluer shade of pale himself once more, twenty years later, in “Tight Connection To My Heart (Has Anyone Seen My Love?)”:

There’s just a hot-blooded singer Singing “Memphis in June” While they’re beatin’ the devil out of a guy Who’s wearing a powder-blue wig Later he’ll be shot For resisting arrest

… again suggesting effeminacy, indeed.

In “115th Dream”, the suggestion is not too subtle. The handsome man wearing the powder-blue cape is introduced with the female job title waitress, which is not elaborated on. It’s 1965, a comic effect has already been achieved by giving a man feminine traits, and this cheap way to score a laugh is being milked long after 1965 in TV comedies, musicals (La Cage Aux Folles is probably the ultimate example) and films like Tootsie, Mrs. Doubtfire and White Chicks. Dylan, too, feels that the joke already has been made with the mere job title “waitress”, and can immediately move on to the next dramatic development: the kitchen explodes and the protagonist flees.

VI A little plumbing on the side

By the mid-sixties, the interviews are getting sillier and sillier, and certainly in press conferences, Dylan’s words are barely worth taking seriously. A fitting finale is the fabricated interview that Dylan concocts over the phone after both he and interviewer Nat Hentoff have seen the proof of an “edited” interview that Playboy intends to print. Hentoff tells: “I got a call and he was furious. I said, ‘Look, tell them to go to hell. Tell them you don’t want it to run.’ And he said, ‘No, I got a better idea. I’m gonna make one up.’”

He has no tape recorder, so at the cost of a colossal writer’s cramp, Hentoff tries as hard as he can to keep up with the unleashed Dylan on the phone. Playboy accepts the “interview” and prints it (March ’66); “It was run as there was absolutely no indication it was a put-on.” Hentoff can’t use his hand for a day, but it’s all worth it and Dylan is content with the prank too. “He thought it was a very funny caper, which it was.”

Actually, it’s a wonderful “interview”, comparable to one of the best “interviews” with Dylan, the “one-act play, as it really happened one afternoon in California” that Sam Shepard wrote for Esquire in 1986 with the title True Dylan, and later actually included as a one-act play in the collection Fifteen One-Act Plays (2012). Not comparable in content (absolutely not, in fact), but in value; both interviews have the paradoxical quality that fiction tells more about the artist Dylan than faithful reportage does. Here, thanks to the wild story Dylan shakes out of his sleeve when asked what made you decide to go the rock n’ roll route. The warmed-up singer gleefully rattles off a 286-word answer with a high 115th dream quality, in which “I” squeezes out a disastrous jack-of-all-trades biography that takes him from Philadelphia to Phoenix to Dallas to Omaha, culminating in:

“I move in with a high-school teacher who also does a little plumbing on the side, who ain’t much to look at,-but who’s built a special kind of refrigerator that can turn newspaper into lettuce.-Everything’s going good until that delivery boy shows up and tries to knife me. Needless-to say, he burned the house down, and hit the road.”

Both in terms of content and style, unmistakably the author of “Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream”. In terms of content, we see a similar stumbling path of a protagonist staggering from conflict to conflict, within an unreal frame. In the interview, Dylan builds that unreal frame by placing geographically absurd distances between the conflicts (over 4,000 miles, roughly from the East Coast to the Far West to the Deep South to the High North), in the song, the time jumps through the centuries provide the surreal frame.

And stylistically we see an identical acceleration; at first the frenzies pass by every two, three lines, then in every following line and it culminates in accumulations of two, three absurdities within one sentence – both the interlocutor Dylan and the songwriter Dylan run on a diesel:

Now, I didn't mean to be nosy, but I went into a bank To get some bail for Arab and all the boys back in the tank They asked me for some collateral and I pulled down my pants They threw me in the alley, when up comes this girl from France Who invited me to her house, I went, but she had a friend Who knocked me out and robbed my boots and I was on the street again

… with which Dylan en passant lays a first building block for intertextuality; a year later, in “Stuck Inside of Mobile with the Memphis Blues Again”, we have a next encounter with the French girl in the alley, and we get some more clarity about the identity of her aggressive, boots-robbing boyfriend:

Well, Shakespeare, he’s in the alley With his pointed shoes and his bells Speaking to some French girl Who says she knows me well

… taking us back to the seventeenth century again.

Bob Dylan – 115th Dream (19.10.1988 New York):

To be continued. Next up: Bob Dylan’s 115th Dream part 4: I knew Thomas Jefferson

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978