by Jochen Markhorst

The Kingston Trio’s track record is staggering. Five number-one albums, four of them consecutive (in 1959 and 1960, the successive records At Large, Here We Go Again, Sold Out and String Along all reached the top position); fourteen Top 10 albums; three Grammy’s; in 22 of the 52 weeks of 1960, a Kingston Trio album was number one, and so on. As a result, the trio is considered mainstream and not appreciated in hardcore folk circles, among snobby college kids and other self-proclaimed purists, but Dylan has always remained a fan. In almost every interview in which he is asked about his musical idols, he mentions the men from San Francisco, among Odetta, Harry Belafonte and Woody Guthrie, and in his autobiography Chronicles he is unequivocal, with one small reservation, as well:

The Kingston Trio’s track record is staggering. Five number-one albums, four of them consecutive (in 1959 and 1960, the successive records At Large, Here We Go Again, Sold Out and String Along all reached the top position); fourteen Top 10 albums; three Grammy’s; in 22 of the 52 weeks of 1960, a Kingston Trio album was number one, and so on. As a result, the trio is considered mainstream and not appreciated in hardcore folk circles, among snobby college kids and other self-proclaimed purists, but Dylan has always remained a fan. In almost every interview in which he is asked about his musical idols, he mentions the men from San Francisco, among Odetta, Harry Belafonte and Woody Guthrie, and in his autobiography Chronicles he is unequivocal, with one small reservation, as well:

“I liked The Kingston Trio. Even though their style was polished and collegiate, I liked most of their stuff anyway. Songs like “Getaway John,” “Remember the Alamo,” “Long Black Rifle.”

… and further on Dylan is even rather exuberant in his admiration:

“Folk music, if nothing else, makes a believer out of you. I believed Dave Guard in The Kingston Trio, too. I believed that he would kill or already did kill poor Laura Foster. I believed that he’d kill someone else, too. I didn’t think he was playing around.”

Dylan names three song titles that can be found on Side 2 of the millionseller At Large (1959, fifteen weeks at #1), and poor Laura Foster is of course referring to the landslide 1958 “Tom Dooley”, the hit that pundits like Joan Baez, John Fogerty and Joni Mitchell say ignited the folk boom, the single that sold more than six million copies, and inspired envious peers The Four Preps to write the witty parody “More Money For You And Me”;

Hang down the Kingston Trio, Hang 'em from a tall oak tree; Eliminate the Kingston Trio; More money for you and me.

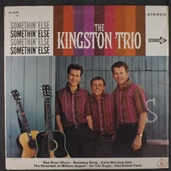

Dylan remains loyal to the Kingston Trio even after they are finally eliminated. From 1965 onwards, the commercial success is over. Stay Awhile does not get any further than a 125th place in the summer, Somethin’ Else from November ’65 doesn’t even make it to the Billboard Top 150 LPs. But it reaches Dylan’s turntable anyhow, apparently. The Dylan cover “She Belongs To Me” is dismissed for the final tracklist, remaining an outtake, which is a shame – although it is, like more of the tracks, a rather frenetic attempt by the men to fit in with the times, and a particularly atypical recording for the Kingston Trio, it still has most definitely an antiquarian charm. And the song is still way better than the slightly bizarre Dylan parody that does pass selection, the wacky “Verandah Of Millium August”, a sort of psychedelic mutilation of “Tombstone Blues”, with presumably satirically intended, bad Dylan imitations in the lyrics such as

The yellow window's hanging on the bed across the wall Well, always in the morning the yellowest of all And the faces of the people in the window look so small And the faces in the morning were the peoplest of all Standing on the verandah of Millium August.

https://youtu.be/iVvx0CguTu4

… and Dylanesque rhymes like Victrola/crayola and someone else’s odour/secret decoder, Dyanesque meant images like a prisoner on a cemetery lane and Dylanesque meant idioms like kaleidoscope and renaissance wallpaper.

Dylan most likely has noted it with some bewilderment, but has in any case already been touched by the song that precedes that weird “Verandah Of Millium August”, by the opening track of Side 2, by “Red River Shore”.

The Kingston Trio’s “Red River Shore” is, apart from the martial drum rolls in the background, a real, old-fashioned Kingston Trio song; the charm of a nineteenth-century folk song, banjo, nice harmony vocals and no new-fangled antics like elsewhere on the LP. No tomfoolery like the funky organ, electric guitar and intrusive percussion in Mose Allison’s “Parchman Farm” (the opening and unlikely single choice), which by the way is spelled rather disrespectfully both on the single and the LP as Parchment; no hooliganism like the all-electric pop rocker “Runaway Song” or the shameless Byrds rip-off “Long Time Blues” – songs the overenthusiastic writer of the liner notes probably is thinking of when he writes: “In places it has a beat born in that jailhouse and baptized in the waters of the Mersey.”

But fortunately, “Red River Shore” is still old-school.

…a narrative ballad with an ancient melody, in a classical arrangement, with a Civil War colour and archaic language;

At the foot of yon mountain, where the big river flows, there's a fond creation and a soft wind that blows. There lives a fair maiden, she's the one I adore. She's the one I will marry on the Red River shore.

… is the opening couplet, which right away explains the nineteenth-century colour; the Kingstons adapt the “Red River Shore” version as collected by the music historian John Lomax and recorded by The New Christy Minstrels (Cowboys And Indians, 1964), an adaptation of the time-honoured “New River Shore”, of which the oldest known version was indeed written down in 1864, during the Civil War.

In all versions we find the text fragment Dylan eagerly saves for reuse:

She wrote me a letter, she wrote it so kind and in that letter these words you will find: Come back to me, darling, you're the one I adore, You're the one I will marry on the Red River shore.

… the words Dylan will transfer during these very same recording sessions in Miami, January 1997, to that other Great Masterpiece, to “Not Dark Yet”, also to the second verse:

She wrote me a letter and she wrote it so kind She put down in writing what was in her mind

“All these songs are connected. Don’t be fooled. I just opened up a different door in a different kind of way. It’s just different, saying the same thing,” as Dylan says in his brilliant MusiCares speech, February 2015.

For his own “Red River Shore”, Dylan radically changes the plot. The Kingston Trio tells of the woman who so badly wants to marry the protagonist, but her father forbids it. The narrator wants to elope with his fair maiden, but Dad sees through it and awaits him with a private army of 24. With his six-shooter, the hero tries to fight his way through (“six men were wounded and seven were down”), but then he has to give up: “I can’t fight an army of twenty and four / when I’m bound for my true love on the Red River shore.”

Which may seem a bit excessive, twenty-four enemies, but compared to his predecessor in the original 1864 version of “New River Shore”, he is still a pathetic sissy:

He raised for him an army Of sixty and four To fight her old father On the New River shore. He drew out his sword And he waved it around Till twenty and four Lay dead on the ground And the rest of the number Lay bleeding in gore, And he gained his own true love On the New River shore.

Somethin’ else, indeed.

To be continued. Next up: Red River Shore part 2 – The importance of capturing spontaneity

Jochen is a regular reviewer of Dylan’s work on Untold. His books, in English, Dutch and German, are available via Amazon both in paperback and on Kindle:

- Blood on the Tracks: Dylan’s Masterpiece in Blue

- Blonde On Blonde: Bob Dylan’s mercurial masterpiece

- Where Are You Tonight? Bob Dylan’s hushed-up classic from 1978

- Desolation Row: Bob Dylan’s poetic letter from 1965

- Basement Tapes: Bob Dylan’s Summer of 1967

- Mississippi: Bob Dylan’s midlife masterpiece

- Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits

- John Wesley Harding: Bob Dylan meets Kafka in Nashville

- Tombstone Blues b/w Jet Pilot: Dylan’s lookin’ for the fuse

- Street-Legal: Bob Dylan’s unpolished gem from 1978

- Bringing It All Back Home: Bob Dylan’s 2nd Big Bang

There’s also the “original” ‘Red River Valley’ song from the Scottish/Metis conflict in Manitoba -no cowboys- that mentions a shunned “dark maiden” that might actually be a burlesque of earlier European folk songs, the former of which Dylan is likely unaware of.

The humorous ‘Veranda’ song certainly a burlesque making fun of Dylan, but when it gets down to the burlesquing of possible burlesque in traditional songs, either high or low, often accompanied with dark humour and hyperbole, things get mighty confusing.

The fog of history intervenes.

I’ll send no more letters unless they’re mailed from Desolation Row.

For Ophelia, I feel so afraid

The blue grass Greenbriar Boys get their name from the song “The Girl On The Green Briar Shore” – in which the gal leaves the guy.

In the Canadian Red River Valley song, the guy leaves the gal.

Dylan performed the traditional Briar song.

In Canadian Wilf Carter’s rendition of Red River Valley, it’s a “half-breed” male, rather than female (Metis maybe ~ half -‘Indian’, half-French) who’s left behind.

In Harry McClintock’s version, it’s an American “cowboy” who’s left by himself in the valley; speaks French though – says “adieu”.